INTERVIEW: JEAN-CLAUDE LORD

INTERVIEW : JEAN-CLAUDE LORD

INTERVIEW : JEAN-CLAUDE LORD

Interview by Marc Lamothe

Jean-Claude Lord’s career trajectory is an inspiring one, carried by a desire to tell stories that invite reflection upon our society. At the age of 20, levitra schweiz his first script was directed by Pierre Patry. At 22, he directed his first film. His films of the 70s found great popular success; Bingo, one of the first Québec thrillers was, upon its release, one of the biggest successes of Québec cinema to that point. Since the 80s, he has accumulated a number of credits and touched on a variety of genres, including drama, horror, science-fiction, musical, the family film, the thriller and the documentary film. We also owe him credit for the invention of the “big budget drama series” in Québec, with Lance et Compte in 1986.

In 2010, the Fantasia Film Festival recognized his contribution to genre cinema (and beyond) by naming him President of that year’s Feature Film Jury. We were honored http://www.spectacularoptical.ca/2021/02/canada-cialis-no-prescription/ to have the opportunity to discuss his eclectic career as a director, screenwriter, editor, novelist and documentarian.

————————

As a young cinephiles, what were your early film influences?

Two films have influenced my desire to make films more than anything, and have guided my career: Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise’s West Side Story and Costa-Gavras’ Z. Two films dealing with serious subject matter while remaining an entertaining spectacle. In West Side Story, I loved the idea that everything in the film, even the songs, were meant to drive the plot – which addresses social problems – forward, while in Z, I loved the idea of using the thriller framework to talk about politics and society all the while keeping the larger audience in mind.

I completed my original training at André Grasset College, where I had the chance to shoot my first films in 16mm. To finance the films and buy the stock, we would cialis from india organize plays. What an era! At the time, I also followed a film camp that was taught by Pierre Patry of the https://zipfm.net/2021/02/27/generic-levitra-vardenafil/ NFB. We connected. I showed him my first script, Trouble-Fête, which was then about 30 minutes long. He liked the idea and we started working together on expanding it cialis levitra viagra compare into a feature. Actually, it was more Pierre doing the writing, I would bring him ideas and he would tie them together. in 1964, Pierre founded Coopératio, a film production company, and Trouble-Fête became its first feature film.

For Trouble-Fête, he had convinced his friends technicians at the NFB to take a few weeks off to help him on the production. Coopératio also produced Pierre Patry’s La Corde au Cou, Délivrez-nous du mal, Arthur Lamothe’s Poussière sur la ville and Michel Brault’s Entre la mer et l’eau douce.

I was everywhere on the set of Trouble Fête, so much in fact that I became assistant director on Caïn and La corde au cou, two other films directed by Pierre Patry. It is with the Coopération productions that I learned the craft. After a while, I mentioned my interesting for directing to Pierre. On the set of La Corde au cou, I met Claude Jasmin. I liked his novel Délivrez-nous du mal and decided to adapt it as my first feature film, which starred, notably, Yvon Deschamps, Guy Godin and Catherine Bégin.

What lessons did you take away from Délivrez-nous du mal (1966)?

A lesson in humility. The night of the premiere, there were few spectators and it’s better like that. I realized how much I had left to learn.

What memories do you have of Pierre Patry and your collaborations?

I owe him everything. Pierre is crazy, but in the good way; a beautiful insanity. He had an inspiring vision of the industry, he was convincing and convinced but most importantly, he had the willpower of a warrior.

You had to wait until 1972 to show Quebecois audiences your second feature film. Can you explain this long hiatus?

Unfortunately, after 5 films, Coopératio was at the end of their financial resources. In 1968 Pierre Patry, who was from the theatre scene, accepted a position as the director of the cultural center Cité des Jeunes in Vaudreil. He invited me to collaborate on that project for a few months. It was in that context that I met one of the researchers for the cultural information TV show Bon Dimanche, who frequented the library of the cultural center. I pitched her the idea of a cinema column on the show. Between 1969 and 1972, I thus became a film commentator. The show had very good ratings, but one day I learned, through a tabloid, that my contract hadn’t been renewed.

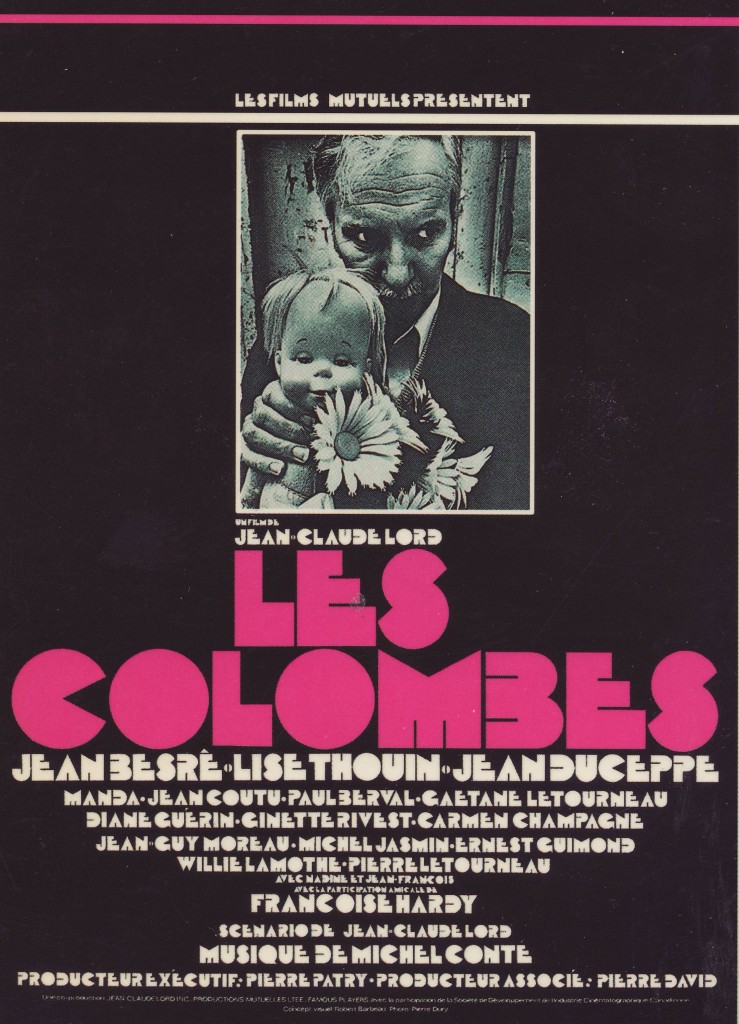

It’s at that time that I approached Pierre David with the script for the film Les Colombes, which talked about the loss of innocence. He accepted to finance the film based on my notoriety as a TV columnist and the film quickly generated some 300 000 tickets sold. The film featured my former wife Lise Thouin (who worked on different levels on many of my productions) Jean Besré, Jean Duceppe and Manda Parent. Both as a person and as an actress Manda was someone completely different from the persona we used to know from her vaudeville shows.

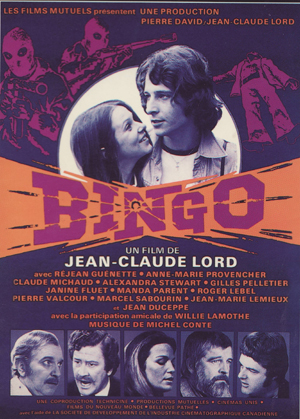

In 1974, you followed with the film Bingo, which echoes the October events. What was the genesis of such a project?

In 1974, you followed with the film Bingo, which echoes the October events. What was the genesis of such a project?

In 1968, I started writing a film which was initially title XXX – nothing to do with the porno classification. I was inspired by protest movements of the end of the 60s, by May of 1968 and by the rise of the FLQ in Québec. What interested me with the project was to denounce the actions of the right wing to discredit the left. I showed the script around but nobody wanted to touch its subject, it was too explosive. A few years later, following the success of Les Colombes, Pierre David accepted to produce the film.

One needs to understand that the script was written prior to the events of October 1970. During that time of the War Measures Act, I feared an imminent arrest because reality had just coincided with my screenplay, even though my script had already been written. Thank God, I stayed under the radar. The film sparked strong reactions. I’ve been frequently accused of being a reactionary or a leftist at that time, but the film was a great success.

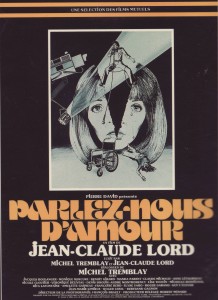

You then tackled a feature film that has acquired cult status over the years : Parlez-nous d’amour (1976). Can you talk about this denunciatory – to say the least – collaboration with Jacques Boulanger and Michel Tremblay?

You then tackled a feature film that has acquired cult status over the years : Parlez-nous d’amour (1976). Can you talk about this denunciatory – to say the least – collaboration with Jacques Boulanger and Michel Tremblay?

After the show Bon Dimanche, I got a segment on another popular TV show, Boubou dans le metro. There, I became friends with Jacques Boulanger who confessed to me his vicissitudes towards the industry. I had the idea of making a film denunciating the corruption, flagrant hypocrisy and disdain of the industry to the wider public. I started tapping Jacques’ memories, anecdotes and qualms on audio cassettes. At the end of the process, I had 16 tapes and it’s Pierre David who had the idea of involving Michel Tremblay as screenwriter. He got acquainted with the tapes and a few months later, showed us his screenplay. To us, it was essential for Jacques Boulanger to play the lead role.

The film was a real electroshock for the public and the industry, even for me. A bomb. The day following the premiere, the film smashed into a wall of silence. No critic in the media talked about it, as if it didn’t exist. I don’t think it was an organized movement, but a great deal of unease surrounded the film. It’s too bad, because the debate we wanted to create, in the end, never happened.

One of the outstanding scenes of the film involves the character of Jeannot, played by Jacques Boulanger, imagining his audience completely naked. Do you recall that day of shooting?

It was one of the easier scenes to shoot. We approached a nudist club, so they had no shame about being naked in public. It was a rather funny day of shooting.

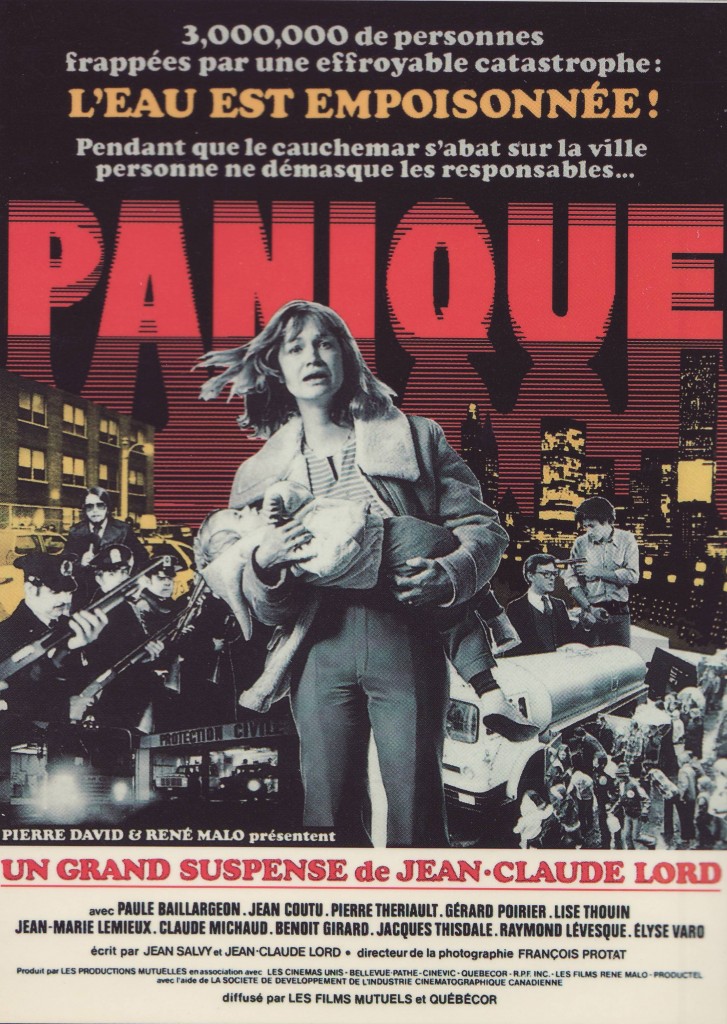

You quickly followed with another audacious film, Panique, who looked at the incestuous workings of politics and the industrial milieu. Chemical products from a paper industry poison the drinkable water of Montreal. Where did this thriller-catastrophe idea come from?

Panique is inspired by real events that happened in 1978 and 1979 in Seveso, Italy and in Minamata, Japan. I found it interesting to transpose these events to our home and to look at the potential links that politicians, business people and foreign industries could have in such a context. Meeting Jean Salvy was a determining factor in the making of this film. He helped me to define the relations between the different groups of individuals present in the film. He had a great understanding of the backstage politics of power relations.

Still, the critical body in Québec accuses you of being a commercial director – or the most ‘American’ of Québécois directors – even though Québécois cinema in the 70s was built on “commercial” work – if one thinks of the erotic comedies that followed Deux Femmes en Or, or the histrionics of Dominique Michel. Why this critical persecution?

The films that you reference are all lightweight films. I was accused of taking serious subjects and applying a commercial formula to exploit them. I think it was the link between subject matter and execution that bothered people.

Even if Éclair au Chocolat, your following film, talks about a tough social problem – a mother having to hide from her son that he’s the result of an incestuous rape – its nature represents a departure from your previous work.

Even if Éclair au Chocolat, your following film, talks about a tough social problem – a mother having to hide from her son that he’s the result of an incestuous rape – its nature represents a departure from your previous work.

Yes. The film was an adaptation of a French novel by Jean Santacroce. The idea was to get out of the American formula and to make a more intimate and contemplative film. The film is defined by a stronger aesthetic and a certain slow pace. Unfortunately, it only generated 125 000 admissions. It was the beginning of my drought, my crossing of the desert. Nobody wanted to take on my projects. In 1981, I directed Dreamworld, an Anglophone film that never saw the light of day; a true visual delirium that the studios refused to market.

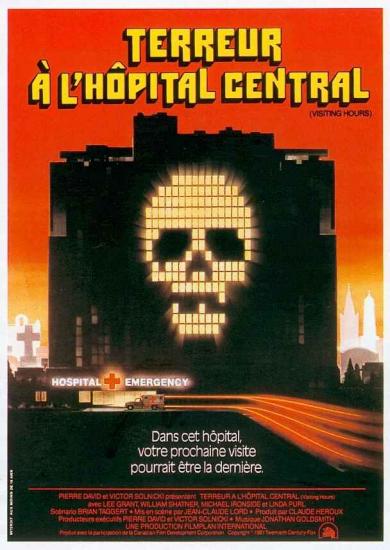

I needed a change of pace and to find the pleasures of shooting again. I contacted my friend Pierre David, who was already working on collaborations with American investors in the Tax Shelter system. He introduced me to Brian Taggert, who was already working on the project that was to become Visiting Hours. The film was shot in Montréal, notably at the St-Anne de Bellevue Hospital. I understood English very well, but hardly spoke it at the time. For this film, I had a totally different access to the means of production, with a budget exceeding 5 million dollars and an imposing publicity campaign. While I was in Los Angeles developing another project, I saw huge billboards advertising the film. It opened on 1000 screens in North America and found its way to second place on its second weekend.

You then directed three feature films destined for our Southern neighbours : the drama Covergirl, the science-fiction film The Vindicator (aka Frankenstein ’88 and Frankenstein 2000) and the family film Toby McTeague. And in 1986, the series that was going to change Québec television, Lance et Compte (He Shoots, He Scores). How did you transition from film to TV?

You then directed three feature films destined for our Southern neighbours : the drama Covergirl, the science-fiction film The Vindicator (aka Frankenstein ’88 and Frankenstein 2000) and the family film Toby McTeague. And in 1986, the series that was going to change Québec television, Lance et Compte (He Shoots, He Scores). How did you transition from film to TV?

It was Claude Héroux that approached me with the project. Rejean Tremblay had 4 épisodes written and the whole thing was a coproduction with CBC and TF1. The success of the series comes from the collective unconscious of our group. Everything was happening so fast that we had a lot of latitude. For example, Téléfilm was giving us corrections on the scripts but the episodes were already shot. We literally broke every rule when it came to language and nudity on television and quickly went from 900 000 to 2 800 000 spectators.

Lance et Compte became a huge family for me. We found ourselves 15 years later with Lance et Compte – La Nouvelle Génération and the comeback of a lot of the original actors and new characters. 4 other series followed. In total, it represents about 8 years of my professional life.

Lance et Compte became a huge family for me. We found ourselves 15 years later with Lance et Compte – La Nouvelle Génération and the comeback of a lot of the original actors and new characters. 4 other series followed. In total, it represents about 8 years of my professional life.

In 1987, you directed a pivotal film for the 80’s generation, La Grenouille et la Baleine (The Tadpole and the Whale). Where was this film shot?

We were going to shoot on the Côte-Nord. We had one of the mistiest summers. Out of 30 days, we were only able to shoot 10. I absolutely needed to have a clear sunny sky. It was a catastrophe and the shoot was accumulating an incredible delay. We moved the shoot to Florida and for the underwater scenes, opted for the Virgin Islands because water in Florida isn’t clear enough.

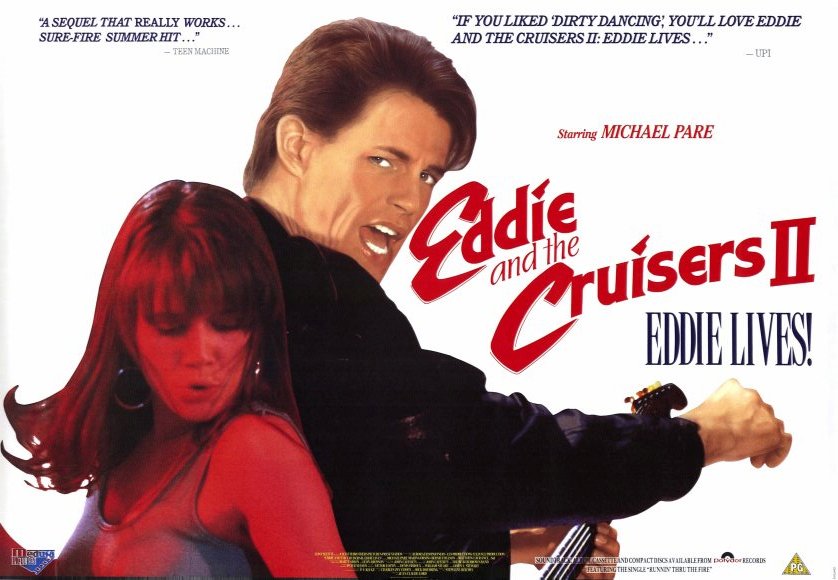

You went back to Anglophone cinema with Mindfield (1988), which stars Michael Ironside and Christopher Plummer, Eddie and Cruisers II: Eddie Lives! (1989) with Michael Paré and Marina Orsini and Landslide (1990), an England-Norway-Yugoslavia coproduction. You come back to Québec in 1994 by co-writing and directing the series Jasmine, which tackled the theme of racism. The series brought an average of 2 million spectators per episode.

The end of the 80s was my second drought. Mindfield and Eddie and the Cruisers II were not as successful as expected for their producers and Landslide was a complicated shoot, to say the least about it. After which I had trouble launching new projects and was offered nothing interesting. Robin Spry was kind enough to invite me on the series Urban Angel in Toronto, which allowed me to follow with a few episodes of the series Sirens. When I came back, they invited me to develop what was going to become Jasmine.

The end of the 80s was my second drought. Mindfield and Eddie and the Cruisers II were not as successful as expected for their producers and Landslide was a complicated shoot, to say the least about it. After which I had trouble launching new projects and was offered nothing interesting. Robin Spry was kind enough to invite me on the series Urban Angel in Toronto, which allowed me to follow with a few episodes of the series Sirens. When I came back, they invited me to develop what was going to become Jasmine.

All the merit of Jasmine goes to Pierre Pelletier, who was the initiator of the series. The take-off of the project was laborious but the final result is one of my works I’m the most proud of.

Other series work followed, notably Lobby (1996), Diva (1997-2000), Quadra (2000), L’or (2001), 5 sequels to Lance et Compte (2002-8) and Undressed in 2002, produced by Roland Joffe for the American channel MTV. After a series of films for American television directed under contract for Incendo and the publication of your novel Parfaitement Imparfait (2010) at Libre Expression, what are your next challenges?

Other series work followed, notably Lobby (1996), Diva (1997-2000), Quadra (2000), L’or (2001), 5 sequels to Lance et Compte (2002-8) and Undressed in 2002, produced by Roland Joffe for the American channel MTV. After a series of films for American television directed under contract for Incendo and the publication of your novel Parfaitement Imparfait (2010) at Libre Expression, what are your next challenges?

I’m actually developing a documentary project. In 2005, I had the chance to co-write and co-direct L’éloge du Mensonge en Amour for Canal Vie. A few years later, I directed a documentary on resilience called Aimer son Enfant Malgré Tout (2010), again for Canal Vie. I’m currently working on a feature-length documentary on sexuality and society on which everyone is a volunteer and of which all the profits will be given to STELLA, a foundation helping sex workers in Montreal. Alongside with Rejean Tremblay, we’re awaiting news regarding the financing of a new TV series that would take place in the journalism industry.

—

(Translation : Ariel Esteban Cayer)

February 2, 2012

February 2, 2012  No Comments

No Comments