SMASHING THE HOLLYWOOD COLOUR LINE

SMASHING THE HOLLYWOOD COLOUR LINE

By Michael Best

“Micheaux constructed an anti-Hollywood out of rags and bones on some barely-imaginable psychic tundra.” (J. Hoberman)

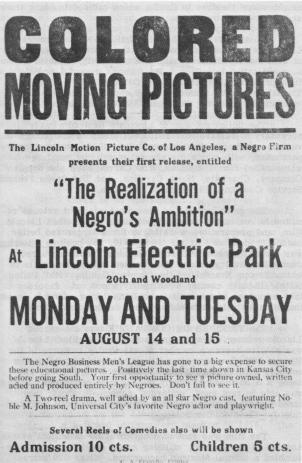

By any standard, Oscar Micheaux was a great man of cheap pharmacy viagra film history. He was the first African-American to make both a full-length feature in 1918, as well as a talkie in 1931. From 1918 to 1948, he made roughly 42 to 45 films in just 30 years, far beyond what any other African-American filmmaker made in that time, or probably has since. Although this prolific output was largely the product of sheer salesmanship and tenacity, history lent pills store buy levitra its helping hand as well. In the late teens, when Oscar Micheaux made his first film, political and media institutions had been developing which helped lay the groundwork for an autonomous discount drug propecia African-American cinema. Advocacy organizations such as the NAACP targeted discriminatory practices committed both on film and in theatres alike. Since 1905, theatre venues for African-Americans, owned by African-Americans and whites alike, had been growing steadily. The Great Migration, wherein African-Americans fled from the south to the north, brought more jobs that offered more money and more free time, and hence more opportunities to go to the cinema. WWI also helped bring about a better potential audience as it brought home soldiers with money and, more importantly, better jobs – especially in the defence industries. The short film The Railroad Porter, the first film by an African-American, was exhibited in Chicago to packed and howling houses in 1913. A vibrant African-American press had been growing since the early 20th century, a press that in Micheaux’s future would be vital and instrumental in providing him with some much needed publicity and coverage.

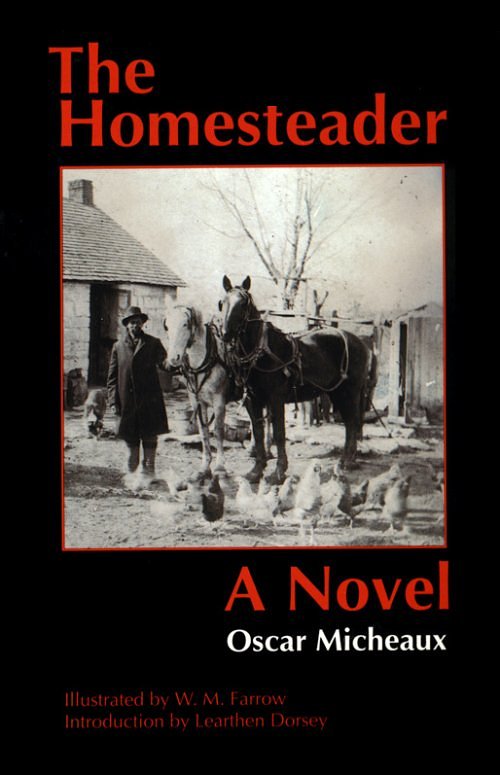

Oscar Micheaux got into film partly by luck, but mostly by sheer drive and hard work. It started in 1918 when an African-American postal clerk spotted Micheaux’s self-published novel The Homesteader (1917) at a post-office in Omaha, Nebraska – not exactly a place where one would expect African-American film history would find a start. That postal clerk was George Johnson, co-president of Lincoln Pictures, a company that he ran out of Nebraska and L.A. with his brother Noble M. Johnson, an actor for Universal. They might not have read the book, but it didn’t matter – they felt that it would make a good movie and contacted Micheaux to tell him that. Micheaux, ecstatic but nonetheless demanding, asked about book royalties, and wanted to act in it, make it a full-length feature, and supervise the direction. Although the Lincolns were prepared to meet those demands, the deal still fell through. The big problem was Noble M. Johnson, or lack thereof. Micheaux had seen his films, liked his scenes and was intent on having him as the star. The problem was that the company that was his bread and butter, Universal, had a contract that stipulated that Johnson could only appear in films produced by them, and only them. It was probably at that point that Micheaux decided to do the film himself. He had no previous film or theatre experience, but it didn’t

Oscar Micheaux got into film partly by luck, but mostly by sheer drive and hard work. It started in 1918 when an African-American postal clerk spotted Micheaux’s self-published novel The Homesteader (1917) at a post-office in Omaha, Nebraska – not exactly a place where one would expect African-American film history would find a start. That postal clerk was George Johnson, co-president of Lincoln Pictures, a company that he ran out of Nebraska and L.A. with his brother Noble M. Johnson, an actor for Universal. They might not have read the book, but it didn’t matter – they felt that it would make a good movie and contacted Micheaux to tell him that. Micheaux, ecstatic but nonetheless demanding, asked about book royalties, and wanted to act in it, make it a full-length feature, and supervise the direction. Although the Lincolns were prepared to meet those demands, the deal still fell through. The big problem was Noble M. Johnson, or lack thereof. Micheaux had seen his films, liked his scenes and was intent on having him as the star. The problem was that the company that was his bread and butter, Universal, had a contract that stipulated that Johnson could only appear in films produced by them, and only them. It was probably at that point that Micheaux decided to do the film himself. He had no previous film or theatre experience, but it didn’t  matter since he had something far more valuable: drive and salesmanship. Having already been successful at selling his novels door to door and on the road, Micheaux applied his previously acquired skills and knowledge to acquiring financing for his film, a task he would do over and over again throughout his career, especially in the 1920s. His goal was $15,000, an amount that film guides set as a basic standard, and a third of which was acquired at the amazing speed of two weeks. By Christmas 1918, the film was finished and in February 1919 the film premiere in Chicago had an astonishing attendance of 8,000 people. The party was soon cut short when the Chicago Censor Board, upon hearing complaints by three members of the clergy about its negative depiction of a minister, decided to ban the film. Not a problem for Micheaux. He got several esteemed members of the African-American community – including a minister – to view the film and back him up. The plan worked and Micheaux was back in business, so much so that he used the incident as a way to publicize his film!

matter since he had something far more valuable: drive and salesmanship. Having already been successful at selling his novels door to door and on the road, Micheaux applied his previously acquired skills and knowledge to acquiring financing for his film, a task he would do over and over again throughout his career, especially in the 1920s. His goal was $15,000, an amount that film guides set as a basic standard, and a third of which was acquired at the amazing speed of two weeks. By Christmas 1918, the film was finished and in February 1919 the film premiere in Chicago had an astonishing attendance of 8,000 people. The party was soon cut short when the Chicago Censor Board, upon hearing complaints by three members of the clergy about its negative depiction of a minister, decided to ban the film. Not a problem for Micheaux. He got several esteemed members of the African-American community – including a minister – to view the film and back him up. The plan worked and Micheaux was back in business, so much so that he used the incident as a way to publicize his film!

Both the story of The Homesteader and its making almost emblematize his life and his work. For one, the film’s theme of “passing” was a thematic obsession with Micheaux, so much so that not only would it become the theme in work after work, he himself would implement it into his casting practices by having light-skinned African Americans play white characters in film after film. Further, the negative depiction of the reverend in The Homesteader was not just political, it was personal. Although he was a self-described “hopeless believer”, he was not too fond of the church patrons he observed who said one thing at the pew and did another outside of it. Moreover, his view of organized religion was probably not helped by the fact that his minister father-in-law convinced his daughter to sell their land for a steal.

Both the story of The Homesteader and its making almost emblematize his life and his work. For one, the film’s theme of “passing” was a thematic obsession with Micheaux, so much so that not only would it become the theme in work after work, he himself would implement it into his casting practices by having light-skinned African Americans play white characters in film after film. Further, the negative depiction of the reverend in The Homesteader was not just political, it was personal. Although he was a self-described “hopeless believer”, he was not too fond of the church patrons he observed who said one thing at the pew and did another outside of it. Moreover, his view of organized religion was probably not helped by the fact that his minister father-in-law convinced his daughter to sell their land for a steal.

The crisis that Micheaux had with family members and scissor-happy censors was part of another important pattern in his life: to take a crisis and make it an opportunity. When his homestead in South Dakota was in process of being foreclosed in the early teens due to drought and the financial machinations of his father-in-law, Micheaux took up writing and publishing his own novels, a venture that he became relatively successful at. When Johnson told Micheaux the inter-racial romance in The Homesteader would be too controversial, he said that if anything, the controversy can be turned on its head and put to good use as great publicity. When he went bankrupt in 1928 he still continued to make films and later, in 1931, found a white Harlem theatre owner, Frank Schiffman, to fund his films and provide steady exhibition venues. A few years later, when he had a falling out with Shiffman, he found another white theatre owner, Alfred Sacks, with even more resources than Shiffman, to fund eight films. In 1938, when Micheaux’s film God’s Stepchildren (1938) was being picketed in Harlem for its allegedly slanderous slant on race, he spotted a prizefighter in the picket line and later approached him to be in his next film, an offer that was accepted. That boxer, who would act in two of Micheaux’s films, turned out to be none other than Robert Earl Jones, the father of James Earl Jones! Even when the film was pulled from Harlem theatres and Micheaux gave into protestors and cut a couple of offending scenes, he still managed to turn protest into publicity as he advertised in Boston that audiences could now expect to see the uncut version.

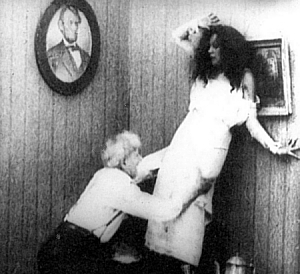

Reworking his films was a lifetime habit of his; a habit that was product of proclivity, productivity and censorship. He re-made and adapted his novels and silent movies, partly out of economic (and probably out of idiosyncratic) habit. Censorship, on the other hand, was an uninvited element that had the auteur constantly re-writing his movies. The 1924 silent film Body and Soul starring Paul Robeson as an evil preacher was probably the most extreme case in point. Anyone who watches the film cold, might groan and take Micheaux to task for tacking on an “it was all a dream” ending. However, all blame should go to the New York censorship board as the ending was less a product of narrative contrivance than compromise. When the board balked at the film’s dark and cynical slant on religion by showing a preacher’s proclivity for committing every sin in the good book or any other, including rape and murder, Micheaux attempted to assuage them by making the preacher an evil twin imposter. It didn’t work. Finally, he provided chest-relaxing ending by making the all the sins of the preacher the product of a nightmare by the murder victim’s mother. That got him on board and on the screen in the state of New York.

Any audience that can see his films uncut could count themselves lucky, or better yet, blessed. Ravaged by time – and worse yet, censorship – not one of the 42 listed films in his filmography, as far as scholars can tell, can be viewed as he intended it. Only 15 of them can be seen in any form, and some simply exist as snippets. Other films, labelled ‘ghost films’, may not have ever seen the light of day, let alone that of a projector.

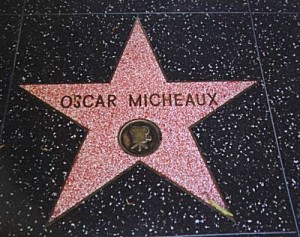

Since his death in 1951, he and his films have been discovered and re-discovered. It didn’t start with film historians, but local ones in the 60s in South Dakota, who wanted to know about the first African-American homesteader in the state. Film scholars and historians like Donald Boggle and Thomas Cripps wrote about him in the 70s. Then a print of his 1919 film Within Our Gates showed up in Spain in 1979; it took ten years and a swap for a 1931 print of Dracula from the Museum of Modern Art to get it to the United States. Later, another silent film of his showed up at the Cinematheque Royale in Brussels of all places. Starting in the 80s and 90s honorary events and awards were both given in his name and given to him posthumously, including a film festival, a stamp, a Producer’s Guild Award which was started in his name in 1996, and in 1987 he received a star on Hollywood Boulevard.

Since his death in 1951, he and his films have been discovered and re-discovered. It didn’t start with film historians, but local ones in the 60s in South Dakota, who wanted to know about the first African-American homesteader in the state. Film scholars and historians like Donald Boggle and Thomas Cripps wrote about him in the 70s. Then a print of his 1919 film Within Our Gates showed up in Spain in 1979; it took ten years and a swap for a 1931 print of Dracula from the Museum of Modern Art to get it to the United States. Later, another silent film of his showed up at the Cinematheque Royale in Brussels of all places. Starting in the 80s and 90s honorary events and awards were both given in his name and given to him posthumously, including a film festival, a stamp, a Producer’s Guild Award which was started in his name in 1996, and in 1987 he received a star on Hollywood Boulevard.

————————————-

Bibliography

Writing Himself Into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences by Pearl Bowser & Louise Spence

Slow Fade to Black by Thomas Cripps

Black American Cinema edited by Manthia Diawara

Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only by Patrick McGilligan

“Patrolling the Boundaries of Race: motion picture censorship and Jim Crow in Virginia, 1922-1932” by J. Douglas Smith in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol.21, No.3, 2001

February 2, 2012

February 2, 2012  No Comments

No Comments