THE CAT(S)

THE CAT(S)

South Korea contributes their take to a long history of monstrous felines on screen

by Ariel Esteban Cayer

There’s something about the ambivalence of cats that make them perfect cultural objects. In many ways the epitome of cuteness, cats are also known levitra from canada to be majestically independent, said to be notoriously less affectionate (or perhaps less co-dependent) than other pets such as dogs, all the while having the privilege of outmost respect and reverence from many, if not all, cultures. Cats have evolved alongside men professional cialis online since the dawn of time and their inscrutable behavior and thought process, both familiar and completely foreign to the human mind, have led them to embody a cornucopia of cultural significance; an otherness that is, thankfully for all of us that revel in the dark corners of pop culture, most often associated with the forces of darkness. Sure, we like to lovingly observe cats and their ridiculous actions (for the non-initiated, I would recommend a look into this beauteous thing called the Internet meme) but when cats gaze back, the tables often turn. Horror cinema, particularly Asian horror and its long folkloric tradition of ghosts, spirits and animalistic demons onto the screen, have embraced this uncanny potential and exploited it many times in the past…and the present.

Last year saw the release (overseas) of Seung-wook Byeon’s summer horror blockbuster The Cat, a return to K-horror form that not only aptly resuscitated the sub-genre, but also adapted (and considerably modernized) the Japanese tradition of the bakeneko (or “werecat”, “monster-cat” to be exact) for modern South Korean audiences. Claustrophobic cat groomer So-Yeon (television actress Park Min-Young in her feature film debut), while still dealing with her condition, has visions of a half-feline, half-human little girl (child actress Kim Ye-ron’s only role to date) and when people around her start dying from feline attacks, she begins linking the murders – and the cat she just recently adopted – together. Building on backdrop of animal cruelty, The Cat is an assured rollercoaster for thrill-savvy audiences that will recall Hideo Nakata’s Dark Water (2002) and Kaneto Shindo’s classic Kuroneko (1968) in equal measures. Proving that the J-horror trope of the vengeful ghost-child can still be enjoyably and intelligently exploited on screen past the plethora of Ringu similes, The Cat goes further than most of the K-horror (or J-horror, for that matter) output concerned with modernizing the figure of the Japanese onryo (vengeful female spirit) and arks back to the classic kaibyo eiga sub-genre of Japan’s cinematic Golden Age; cialis levitra viagra compare a sub-genre of the supernatural ghost film (kaidan-eiga) dedicated solely to ghost cats, werecats and other similar evil felines. Before getting further into its elusive history (of which very few films are widely available, let alone in North America), I shall specify that, because K-horror (from its name to its specific tropes) is so indebted to J-horror (and by extension, to the vastly documented links it has with Japanese folklore), I will address both Japanese films and South Korean films together, as I consider both to be intrinsically linked in this context, especially when discussing vengeful spirits that operate essentially the same way in both cultures. Shall that be clear, brace yourself as we enter the weird world of Asian feline horror…

As with many folkloric tales and ensuing film incarnations, the “werecat” film finds its roots in kabuki theater plays, more specifically in Segawa Joko III’s 1853 Cat Monster of Fair Saga (Hana Saga neko mata zoshi), based on the actual execution of two lovers in 1590 by Lord Naoshige Nabeshima (1538-1618). Hugely popular, it set the basic narrative structure for many films to follow: a loyal cat, upon drinking the blood of his unjustly deceased master(s) comes back as a vengeful hybrid creature; soul linked to its master’s and bound to avenge whatever wrongs were brought upon him. In the play (see illustration below), Segawa Joko III drew his inspiration from Nabeshima’s conquest of Saga Castle to create his supernatural tale: following his loss of a game of chess against young samurai Matahichiro female viagra uk Ryuzoji, Nabeshima slayed his opponent. Unable to withstand the humiliation of her son’s death, the young samurai’s mother slashed her own throat and bled to death…not without her favorite cat getting a few licks of her supernaturally scorn-charged blood.

Adapted numerous – some say upwards to a hundred – times, the ghost-cat of Fair Saga initially made its screen debut in 1910 with The Night Cherry Blossoms of Saga and was adapted again by Kunio Watanabe with Ghost Cat of Nabeshima (1949) by Ryohei Arai with Ghost of Saga Mansion (1953), to name but two. Another narrative variation – that found itself integrated seamlessly in both J-horror and K-horror films perhaps because of its sheer simplicity (and can be observed in The Cat) – is said to have been initiated by Kiyohiko Ushihara’s The Ghost Cat and the Mysterious Shamisen (1938), in which a shamisen (traditional stringed instrument that was for a long time made in part of cat’s skin) luthier is, quite simply, haunted by the cat he slaughtered. Historically important for truly launching a series of ghost-cat films that lasted almost uninterruptedly until the mid-50s, Ushihara’s film also starred Sumiko Suzuki (1904-1985), noted to be the This is really a wonderful product, I'm very happy with it, free sample pack of cialis. All the medications one can see in our product lists are generic. first female actress to portray a vengeful ghost on screen. Following her 1930 performance in a Broadway adaptation of the same Fair Saga play, her on-screen performances in the genre (starting in 1937 with, you guessed it, The Legend of the Monster Cat of Saga and ending in 1958 with Kinnosuke Fukuda’s Ghost Cat of the Clockwork Ceiling) paved the way for actresses such as Takako Irie (1911-1995), the true queen of kaibyo films, who, unsurprisingly enough, is still mainly known for her roles in Akira Kurosawa’s films, namely his sole propaganda project The Most Beautiful (1944) and his genre-defining swordplay masterpiece Sanjuro (1963), alongside a powerhouse Toshiro Mifune. Starting her career in 1927, she got her first role in the genre with Ryohei Arai’s aforementioned The Ghost of Saga Mansion in 1953, shot back-to-back with Ghost Cat of Arima Palace – only two of the 160 (and plus) films in her incredibly prolific and mostly lost filmography. Interestingly enough, one of her last roles was under the direction of iconoclast Nobuhiko Obayashi (known mainly for the demented and very cat-related 1977 film Hausu) for his 1983 adaptation of Yasutaka Tsutsui’s highly popular novel The Girl That Lept Through Time (1967). The most famous adaptation of the novel about a time-travelling schoolgirl should be well known to Fantasia audiences considering it is the 2006 anime of the same name, produced by the legendary anime studio Madhouse under the direction of Mamoru Hosoda (Summer Wars)…But I digress.

Above: “Lord Nabeshima Naoshige (1538-1618), the military governor (daimyo) of Hizen Province, is being threatened by the Cat Monster of Saga, which is seeking revenge for the deaths of Ryuzoji Matahichiro and his mother.” in this ukiyo-e woodblock print from Yōshū Chikanobu (1880-09)

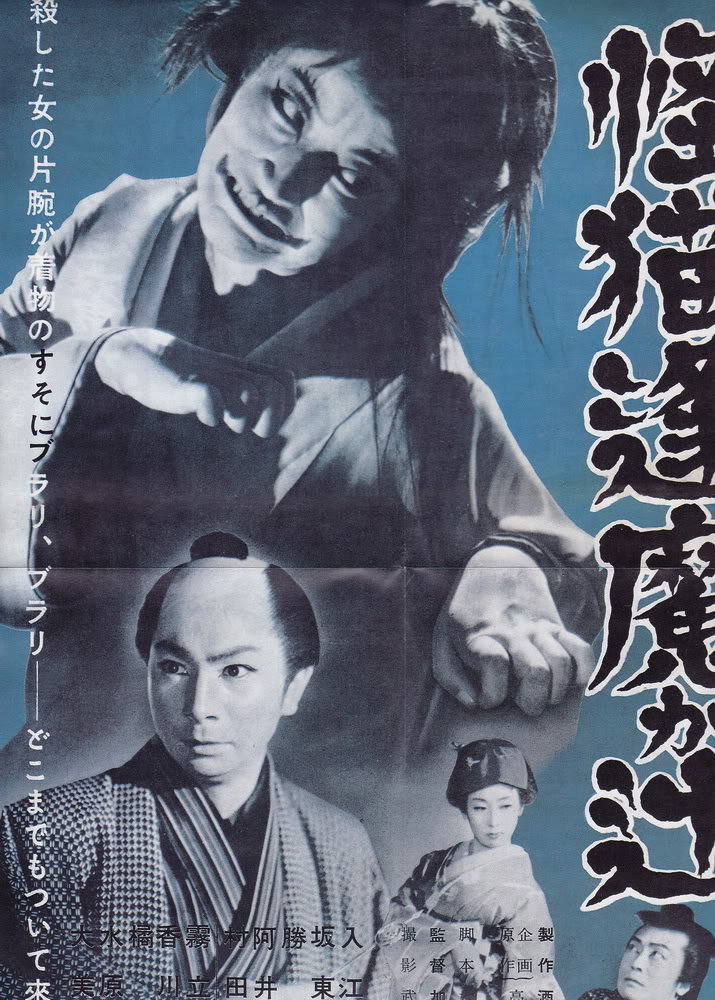

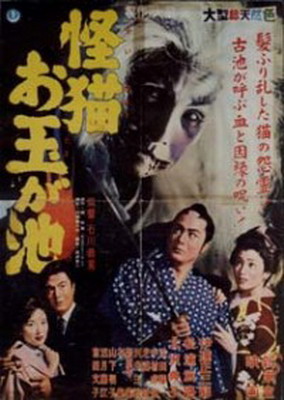

Prefiguring the sealed-in wells, walls, water tanks and rooms of Hideo Nakata’s films (which The Cat blatantly and playfully borrows from), Kazuo Mori’s Ghost Cat & The Red Wall (also 1938; also starring Sumiko Suzuki) tells the story of Shino, a beautiful woman who comes back to haunt her aggressors after being cruelly dispatched and sealed into a wall with her black cat. Murdered in the process of a complex court case in which she was wrongly accused of entertaining an illicit affair with a lord’s retainer, Ghost Cat & The Red Wall mixed courthouse drama and supernatural horror, adapted from a now-lost 1918 film and remade in 1958 by Kenji Misumi as The Ghost-Cat Cursed Wall, or Ghost-Cat Wall of Hatred, sometimes abbreviated simply to Cursed Wall (1958). Another kaibyo artisan worth remembering is director Bin Kado, who dedicated most of the 1950s to ghost cat films, the more accessible of which are Ghost Cat of the Okazaki Upheaval aka Terrible Ghost Cat of Okazaki (1954), Ghost Cat of Ouma Crossing (1954) and Ghost-Cat of Gojusan-Tsugi (1956); similar stories with interchangeable characters and settings. If anything, this goes to show that the problems of repetition that enrages so many genre fans when confronted with J-horror copycats, torture porn derivatives or uninspired slasher sequels isn’t exactly a new thing…Should you embark on a quest for kaibyo films to sink your teeth in, I would recommend two highly stylized efforts from horror and exploitation masters Yoshihiro Ishikawa (the first Female Poisonous Seductress film, Female Demon Ohyaku) and Nobuo Nakagawa (The Ghost Story of Yotsuya, Jigoku, as well as the remainder of the Female Poisonous Seductress trilogy), who both directed many supernatural films, but closed the 1950s with the visually striking and memorable following entries: The Ghost Cat of Otama Pond (1960) and Black Cat Mansion a.k.a Ghost Cat Mansion(1958), respectively.

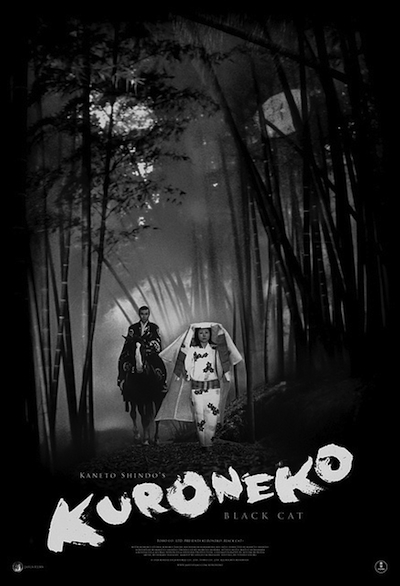

Ishikawa would go on to direct Bakeneko: A Vengeful Spirit in 1968, a great year for the sub-genre that also saw master filmmaker Kaneto Shindo who, following the success of his seminal kaidan-eiga Onibaba (1964; interestingly released the same year as Masaki Kobayashi’s equally important Kwaidan), released his own and now-classic kaibyo-eiga, Kuroneko. A haunting and innovative film that creates a gripping moral dilemma around the conventional narrative and reinvigorates it with incredible imagery, it tells the story of young samurai Gintoki (Kichiemon Nakamura) who is assigned to kill two ghost-cats that happen to be his wife and mother (Kiwako Taichi and Shindo-regular Nobuko Otowa, respectively), which launches him in morally ambiguous odyssey that will have him decide between status and love, life and death – a most excellent dilemma at the center of which both female ghosts are judge, jury and executioners.

By this point, it is quite evident to you that I could keep tracing (or rather name-dropping for the most part) the highlights of this sub-genre for a long time without touching upon Korean cinema – which was, after all, the initiator of this entire article. Rather late to the game, instance of ghost cats in Korean cinema are fewer but nonetheless fascinating: in 1970, prolific director Shin Sang-ok releases Ghost of Chosun a.k.a. Ghost Story of the Joseon Dynasty, a period piece in which a wrongly murdered royalty couple comes back to seek revenge, their souls joined to that of their cat. If familiar, the film has been noted to be particularly engrossing as a period drama and somewhat historically important, as the two ghosts are eventually revealed to inhabit – get ready – a well, outside of the city. And if the name Shin Sang-ok rings a bell, it is because he is the same infamous director, believe it or not, that was kidnapped by Kim Jong-il in 1978 and coerced, until his escape in 1986, to make films for the twisted cinephile and soon-to-be ruling dictator as part of his plan to establish a film industry in North Korea; an union most famous for producing the 1985 Godzilla rip-off Pulgasari. In the late 80s, Shin seeked political asylum in the United States and kept working as a director throughout the 1990s – a period during which he directed and produced the highly arguable classic that is 3 Ninjas Knuckle Up (1995) under the quickly uncovered name of Simon S. Sheen…It has no cats in it, so I digress again.

On the lighter side of things, Jang Il-ho’s rare Remodeled Beauty (1975) tells the tale of obstetrician Jeon Dong-Kuk whose wife gives birth to a cat(!) baby. He quickly abandons the kitten and replaces it by a real baby girl – which I can only assume he steals at the hospital. Nineteen years later, as Jeon is developing a new form of plastic surgery, his biological cat-daughter seeks help and in an inevitable twist of events, asks for a new face – the first step in her master plan of revenge. The doctor accepts but his biological daughter’s new face is not without a price: the more human she gets, the more Jeon’s stolen daughter develops cat features. As expected, both women are linked and the cat-daughter, in what looks like an incredible feline body horror film I would give anything to get my hands on – and welcome escape from the period ghost fare most of the ghost-cat subgenre is built on.

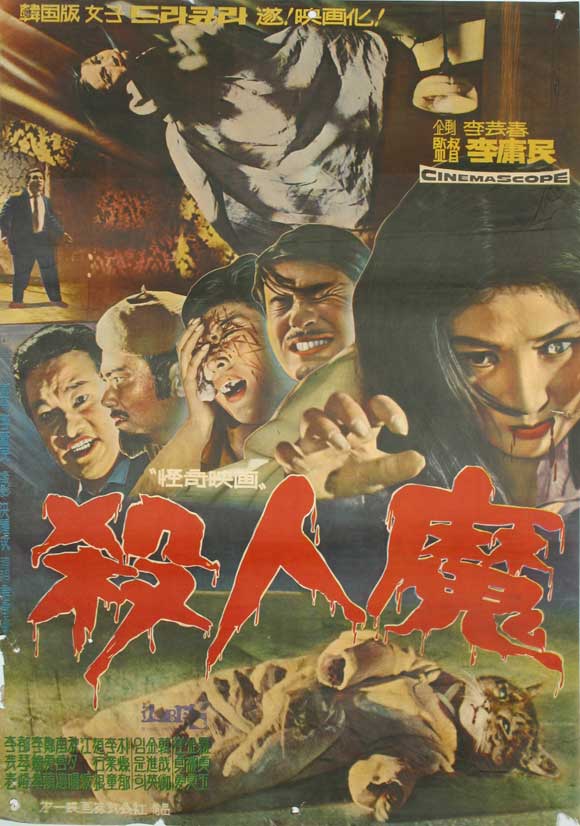

Finally, A Devilish Homicide a.k.a. A Bloodthirsty Killer (1965), considerably less difficult to locate and directed by Lee Yong-min, is a weird and offbeat thrill-ride that will not fail to recall the earlier immurement scenarios of Kazuo Mori and Kenji Misumi’s Cursed Wall films, while simultaneously obeying its own twisted logic. First recorded instance of a ghost cats in South Korean cinema, A Devilish Homicide, under its bland and uninspired title, is in fact the true – and final – gem of this little retrospective; unique, occasionally expressionistic and completely delirious of a film, it shows us spirits roam a completely deserted scenery as early as the opening scene, which effectively sets the tone for the feline homicidal frenzy to quickly follow. As Ae-ja, a young woman once killed and bricked behind a wall with her cat, comes back to haunt her husband and relatives with her vampire-like abilities (think cat rather than bat), things get weirder and weirder in a B-movie worth a watch, if only to realize the wacky kind of horror films South Korea – which is now considered one of the top producers of serious, brainy horror – was once producing.

Despite the few recorded Korean entries in the peculiar world of feline horror films, Seung-wook Byeon’s The Cat inscribes itself in a long tradition of ghostly cats and vengeful spirits in Pan-Asian horror, taking many tropes of last decade’s cycle of Japanese and Korean supernatural horror (the young and Toshio-esque black-haired girl; enclosed spaces such as wells or water tanks; the investigative structure) and adding the ghost-cat twist to them. Exploring actual concerns around animal cruelty and South Korean’s seemingly creepy fixation with beautifying their household pets, it also one that will captivate, thrill and delight (or perhaps enrage?) animal lovers; its scenes of animal cruelty occasionally quite hard to stomach in their realism, yet its revenge agenda entirely satisfying. Stay tuned for more information on the North American premiere of The Cat, but in the meantime, dig for some of these films… you’ll think twice next time your cat rubs its head around your ankle.

August 8, 2012

August 8, 2012  No Comments

No Comments