DEAD TECH: FOUND FOOTAGE AT FANTASIA

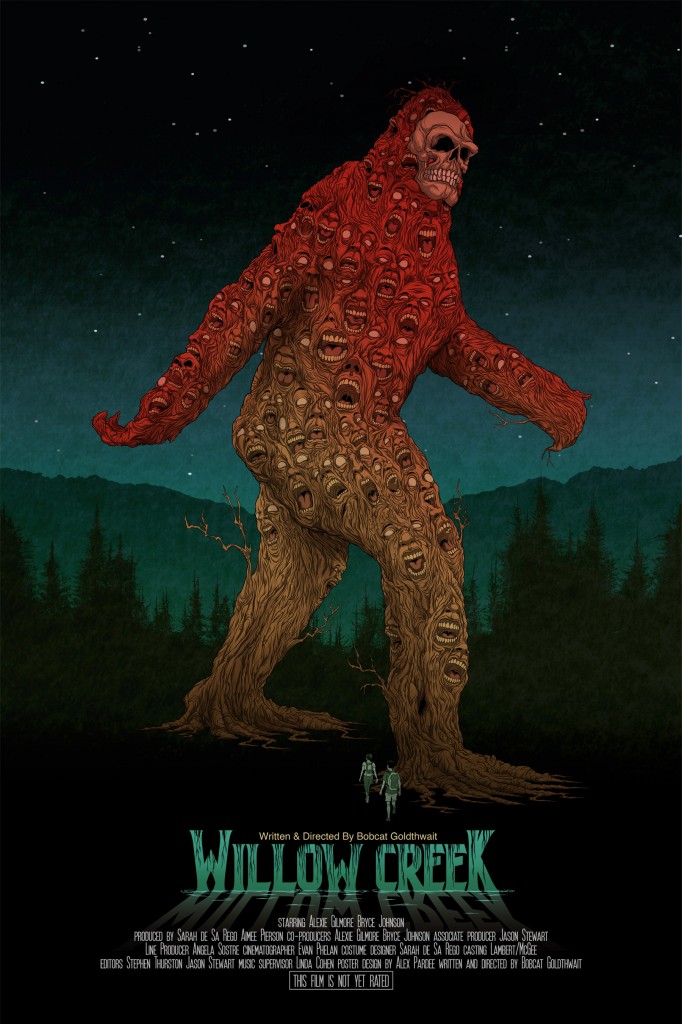

The Canadian Premiere of Bobcat Goldthwait’s Willow Creek (2013) and a Report on Found-Footage and Related Horror at Fantasia 2013

There is an unsettling moment in Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick’s breakthrough 1999 found-footage film, The Blair Witch Project, where the film’s three documentary filmmaker-characters—lost, harried and exhausted by days of exposure to the unforgiving torments of the woods—realize that they have circled back upon the same fallen tree, even though they have been using a compass to guide them out of the woods. In keeping with the film’s conceits around characters beholden to the recording technology that has brought them into the woods, this return to the same spot suggests the characters are caught in a sort of video loop. In The Blair Witch Project, reality itself seems to have gone supernaturally tech, and this same thematic resonates throughout subsequent so-called “found-footage” horror films that revisit or revise the Blair Witch model, such as the mostly-strong Paranormal Activity series (2009-present); the excellent super-hero horror film hit, Chronicle (Josh Trank, 2012); George A. Romero’s under-appreciated Diary of the Dead (2007); and outstanding lesser-known entries such as Home Movie (Christopher Denham, 2007) and Lake Mungo (Joel Anderson, 2008).

Bobcat Goldthwait’s cryptid creature feature, Willow Creek (2013), which had its Canadian premiere on Monday, July 29th, at the Fantasia International Film Festival, is itself a sort of circling back to The Blair Witch Project. When it’s not cribbing shamelessly from Sanchez and Myrick’s (far superior) film, it works as a compendium of the most irritating found-footage horror weaknesses that have come in Witch’s wake. Actors mug for the viagra generic 100mg camera and improvise dialogue that comes off as cloying rather than witty. Frenetic camera movement and murky imagery create a blur aesthetic that makes you feel as if you were watching the film too close to a hand-held screen in the back of a pickup truck. And a loose narrative and structure meant to seem “natural,” end up seeming merely repetitive, episodic, amateurish and flaccid.

In a moment not so much inspired by, as entirely ripped from the Blair Witch scene mentioned above, Willow Creek’s two hapless characters stumble upon the same jagged tree where they earlier found a strand of Bigfoot hair. In the logic of Goldthwait’s film, this moment plays less thematically than practically—the characters are likely being herded by the monster(s) lurking in wait to pounce upon them. Rather than providing further intrigue regarding the Bigfoot legend—or even paying clever homage to Blair Witch—this moment falls flat, serving as a reminder that it takes more than a concept, a forest, an affordable camera, and some improvisational actors to create (or revive) a horror myth.

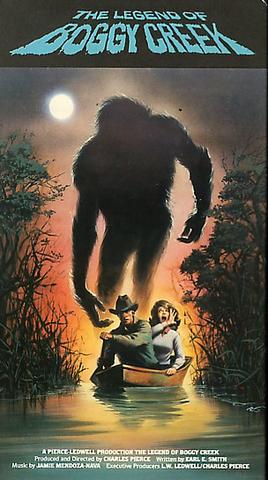

At the center of Willow Creek is the infamous documentary footage (or hoax footage, depending on whom you ask) shot by Roger Patterson and Robert Gimlin in 1967, which appeared to have recorded a large, fur-covered female biped stomping into the thick woods of Northwestern California (Watch it here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nc–kJ1EpZM). One of Willow Creek’s main characters, Jim (Bryce Johnson), more of a home-movie maker than Blair Witch’s ill-fated documentarians, is obsessed with the Patterson-Gimlin film, and sets out to explore the Bigfoot legend, which has been firmly rooted in North American folklore for the better part of the 20th Century, and featured or alluded to in numerous pseudo-documentaries (notably on TV’s In Search of …, 1976-82) and even a subplot of TV’s The Six Million Dollar Man (1974-78). One such film, 1972’s The Legend of Boggy Creek, itself an influence on Blair Witch, outdoes Willow Creek in its effective, hybrid documentary-horror exploration of the similar legend of the “Fouke Monster” in the swamp regions of Arkansas. Here, director Charles B. Pierce (The Town that Dreaded Sundown, 1976) uses a combination of haunting nature footage, eerie sound effects, the stories of real locals, and siege-film aesthetics. The primary draw of Bigfoot as a mystery monster is its implications as a sort of primal alternative to the idea that “civilization” implies inhabiting the labyrinths of towns, cities and suburbs instead of the darkness of the forest. Bigfoot is a liminal creature, a marginal creature, and s/he serves to complicate notions of progress, civilization, and humanity. Part of the power of such legends is that they affect culture as more real than real because of their inconclusiveness and resistance to “capture.” The fact that the Patterson-Gimlin footage offers only a tantalizing, fleeting glimpse of the Bigfoot monster is its primary lure—and its most significant contribution to the aesthetics of the found-footage sub-genre.

News of a new found-footage horror film tends to be met with a general eye-rolling from horror fans, but I have high hopes that this subgenre offers the greatest potential for horror filmmakers to experiment with narrative ambiguity, nontraditional editing, and the horrific potential of the limitations of our much-celebrated, pervasive new media technology. Horror narrative and documentary narratives share a basic quest for knowledge. As Noël Carroll argues in The Philosophy of Horror (1990), horror narratives are based upon the audience’s curiosity and desire to know about monstrous entities that defy standard categories, and found-footage horror offers a promising way to complicate that relationship by largely refusing to answer the questions they raise. The failure of the recording technology in many of these films to capture conclusively and comprehensively what we really want to see is a large part of the horror in the found-footage horror cialis online doctor film. The often dizzying and disturbing implications around shocking accident have also been the lure of the hoax film and the snuff film.

News of a new found-footage horror film tends to be met with a general eye-rolling from horror fans, but I have high hopes that this subgenre offers the greatest potential for horror filmmakers to experiment with narrative ambiguity, nontraditional editing, and the horrific potential of the limitations of our much-celebrated, pervasive new media technology. Horror narrative and documentary narratives share a basic quest for knowledge. As Noël Carroll argues in The Philosophy of Horror (1990), horror narratives are based upon the audience’s curiosity and desire to know about monstrous entities that defy standard categories, and found-footage horror offers a promising way to complicate that relationship by largely refusing to answer the questions they raise. The failure of the recording technology in many of these films to capture conclusively and comprehensively what we really want to see is a large part of the horror in the found-footage horror cialis online doctor film. The often dizzying and disturbing implications around shocking accident have also been the lure of the hoax film and the snuff film.

A number of the selections at this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival form something of a sub-theme around the aspects of media formats that serve to haunt and I was searching reliable online shop for my delicate purchase and here it is! :) Purchasing cialis in canada: the difference between a brand name medicine and a generic one is in the name, shape and in the price. unsettle us with their implications. The Zapruder film (Watch it here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Lzl0RrwY7w), Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm home movie footage capturing the assassination of John F. Kennedy—and perhaps history’s most famous snuff film—haunts the 1982 documentary, The Killing of America, presented on 28 July at Fantasia by Simon Laperrière and Antonio Dominguez Leiva as part of the book launch for their book, Snuff Films: Naissance d’une légende urbaine (June 2013). Co-written by Leonard Schrader (brother of filmmaker Paul Schrader), The Killing of America deploys a string of real atrocity footage from American history as a rhetorical strategy to undercut pharmacy selling viagra in israel the American dream of accessibility and prosperity, and to denounce the unfettered availability of weapons to American citizens. The film’s shocking imagery is undeniably fascinating, and the fact that The Killing of America verges on fetishism and exploitation of its death imagery (often lingering over it, or replaying it in slow-motion), is, again, a testament to the kind of attention the public enjoys paying to the emotions, collective and individual, generated by these suggestive, yet ultimately incomplete historical records.

Picking up on a similar theme, writer/director/actor Matt Johnson’s high school shooting thriller, The Dirties (2013), screened at Fantasia on 21 and 28 July, uses found-footage style to poignant effect. Johnson deftly explores the hot-button issue of school bullying with an astonishingly assured combination of humor and horror. The Dirties picks up on the found-footage film’s visual play with presence and absence in that its camera operator (or operators?), often directly addressed by Johnson as he makes his film-within-a-film, are silent and ubiquitous (they are even present at Johnson’s sleepover with friend, Owen), suggesting a sort of constant media surveillance that collapses public and private spheres. While not strictly found-footage horror, Johnson’s film creates something of a hybrid that suggests the promising use of the sub-genre for personal filmmaking that undercuts the idealistic imagery of American family and community found in the traditional home movie.

Much more in-line with the horrors of Willow Creek is V/H/S/2 (2013), which had its Canadian premiere at Fantasia on 20 July. The follow-up to what increasingly seems to be an arena for good filmmakers (notably personal favourites Adam Wingard and Ti West) to make the pointless short film equivalent of a bad joke (even Gareth Evans/Timo Tjahjanto’s otherwise interesting “Safe Haven” sequence reveals a similar punchline), V/H/S/2 fails on its promise to comment on the growing nostalgia for different forms of “extinct” media. Playing on the conceit of stacks of tapes that feature short, horrific films which mesmerize their viewers, V/H/S/2 has at heart the idea of visual media as a haunted archive of nostalgia. Perhaps this is why both V/H/S films feature segments that recall or revise older horror and science-fiction staples. In V/H/S/2, this comes in two of the film’s four segments, one devoted to Eduardo Sanchez and Gregg Hale’s mildly amusing first-person-camera twist on the nearly-spent zombie film, and the other Jason Eisenberg’s twisted alien invasion segment, which plays like Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) crossed with the nerve-jangling terror of Olatunde Osunsanmi’s hugely underrated alien-invasion / found-footage hybrid, The Fourth Kind (2009). To his credit, Eisner takes Spielberg’s commitment to exploring the worlds of children and teenagers in E.T. to levels of honesty that Spielberg hasn’t achieved outside of his more “serious” efforts such as Empire of the Sun. He also has the inspired audacity to shoot much of the segment with a camera attached to the family dog.

The mashing-up of the fantastical nature of horror, the randomness of the home movie, and the bid for objectivity of the conventional documentary in these films offers a simultaneous nostalgia for, and dread of, the numerous recording technologies available to us. They also tend to lionize the foggy, glitchy, scratchy, staticky nature of obsolete technologies such as 8mm film and VHS, in ways that suggest a sort of nostalgia-horror. Horror has always responded to technology, but not so often with the mix of celebration and ambivalence that found-footage films bring to the fore.

On a related note, the Fantasia screening I saw directly before Willow Creek was the deeply nostalgic documentary feature, Rewind This! (Josh Johnson, 2013), which manages to evoke a sense of loss regarding a once-dominant format, especially in the domestic distribution of horror, and underscores the need for its preservation. The VHS collectors featured in the film are passionate, funny, canny and observant. And it’s a treat to see horror genre heavyweights like Frank Henenlotter wax philosophical about the hand-painted cover art that graced so many 1980s VHS boxes. I only wish there had been a bit of critical framing of these subjects’ (and the film’s) fetishism of the VHS format. Granted, Rewind This! is geared towards a converted audience of VHS fetishists, not to those seeking to investigate the cultural implications around obsolete technologies. But it still doesn’t go far enough into the reception and distribution, and the cultural and aesthetic force of the VHS format.

I am pleased to see such a number of selections at Fantasia this year provide ample evidence of the pervasiveness and hybridization of the “found footage” horror sub-genre. One of the highlights of the festival for me, Lorenzo Bianchini’s Oltre Il Guado [Across the River (2012)], generates much of its realist horror from the nighttime surveillance footage of a scientist (played by Marco Marchese) documenting and tracking animal movement in a thickly-wooded atmosphere, and eventually an abandoned town, that more than once recalls the uncanny qualities of the woods of The Blair Witch Project. While not strictly a found-footage horror film, Across the River inventively adopts its visual aesthetics of absence in framing that suggests found-footage horror’s love of imagery that makes every space seem just on the verge of divulging something monstrous.

August 5, 2013

August 5, 2013  No Comments

No Comments