A HISTORY OF BRITISH FOLK HORROR

England is an old country. There’s evidence of us as a Mesolithic people 15,000 years ago, and the beginnings of a settled society, rituals, religious worship and farming – the first Field in England, in fact – in the Neolithic period. The first version of Stonehenge began to be assembled around 2800BC; the first stones were laid there in 2200BC; and the final phase started around 1600BC. We had a society in the Bronze Age, roughly contemporaneous with Homer’s Troy. The Romans invaded in 55BC. The Vikings hit us in 790 and 866AD, taking Nottingham, York and Northumberland before being kicked out by Alfred the Great in 878. And the Normans took us in 1066, irrevocably fusing their own culture with ours.

“The legacy of prehistory is all around us,” says Peter Ackroyd in his History of England. “The clearances of prehistoric farmers helped to create the English landscape, and there are still places where the land follows its prehistoric boundaries. Modern roads follow the line of ancient paths and trackways [many of the roads we think of as “Roman” simply utilised routes that were already there]. The boundaries of many parishes follow ancient patterns of settlement.” Ancient burials are often still to be found, and much of our archaeology has come from still-extant barrows where “the dead reside upon the landscape”. The layouts of churches often still “obey old laws”. The weathercocks that still adorn church steeples refer back to Iron Age beliefs that cockerels were a defence against thunderstorms.

Villages still keep up their peculiar traditions: rolling cheese down a steep hill once a year in Brockworth, Gloucestershire; or running around carrying burning tar barrels in Ottery St Mary, Devon. “We still live deep in the past,” says Ackroyd. We have a lot of history, and a lot of folklore. If anything, it’s amazing that we haven’t delved into that heritage more in our horror movies.

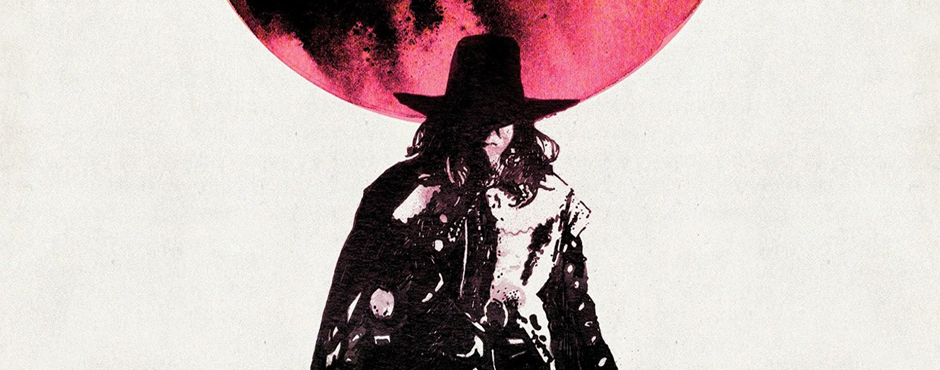

Can we make a genre of English “folk horror”? Recent films like Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England and Elliot Goldner’s The Borderlands suggests two new entries in a longer tradition, but at its core that tradition seems only really to comprise three films: Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (AKA, to some of you guys, The Conqueror Worm, 1968); Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1970); and of course, Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). As we’ll see however, there’s more to be found if you dig: much of it from weird ‘70s British television that would almost certainly never be commissioned now.

Folk horror in literature could fill a whole other feature, so we’ll restrict this article to screen versions. Suffice to say though, that there’s a huge vein of written material out there (much of it out of copyright and online for free), particularly from the ghost story’s huge explosion of popularity in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Authors of MR James and Algernon Blackwood’s ilk regularly plundered history for their scare tactics, and there’s a useful list of works by them and their contemporaries to be found at the blog folkhorror.com.

While Blackwood wasn’t much filmed (an episode of The Twilight Zone; a segment of the anthology Dead of Night), James enjoyed an interesting afterlife at the BBC during the 1970s, where several of his ghost stories were adapted for one-off dramas shown at Christmas. All are currently available on DVD in a BFI collection released just last year. The stories adapted include A Warning to the Curious, based on James’ invented legend of The Three Crowns of Anglia, buried to protect England from invasion and guarded by supernatural sentinels; The Stalls of Barchester, about the curse of a 17th-century carver of cathedral decorations; The Treasure of Abbot Thomas, about a theologian searching for the best-left-alone trove of a disgraced predecessor; and The Ash Tree, in which a man inherits a house chillingly cursed by an ancestors involvement in the 17th Century witch trials. James, himself a medieval scholar, was fond of making his stories’ protagonists meddling antiquarians, whose investigations unearth things better left buried. When the annual series left James behind, there was still a further BBC Christmas folk-horror yarn in a more modern style that nevertheless tapped into even older horrors. Clive Exton’s Stigma, an original piece for television, involves a family who attempt to move part of an ancient stone circle in their garden, unearthing the ritually sacrificed witch and her attendant curse buried beneath.

Elsewhere on British television at around the same time (it was broadcast over eight weeks at the end of 1969 and the beginning of 1970) you might have caught The Owl Service, adapted by Alan Garner from his own novel and intended, extraordinarily, as a serial for children. Actually taking place in Wales (the fractious relationship between the Welsh and English cultures is part of the subtext), this superbly strange tale involves three children destined to repeat the events of a violent love triangle from a local legend. Previous generations have attempted to bind the dark magic in works of art (the titular dinner service; a wall painting) but obviously with limited results. A standing stone and a tree containing ancient artefacts form important parts of the story. Peter Ackroyd and Iain Sinclair (among many others) have written about the notion of “psychogeography”, where locations are deeply informed by echoes of their history. The Owl Service, and folk horror in general, map onto that theory well, and it’s explicitly the basis of Ackroyd’s novel Hawksmoor and Alan Moore’s From Hell, both of which are rooted in multiple eras in London.

Children of the Stones (1978), about a village within a megalithic stone circle, has some overlap with The Owl Service in that it’s about events repeating themselves (and also in that it’s completely terrifying and supposed to be for kids); Doctor Who investigated The Daemons (archaeology, witchcraft and Morris Dancing in rural Wiltshire) and The Stones of Blood (druids and megaliths in Cornwall); and while it’s stretching a point to really call it horror, there’s a lot of black magic and dark folklore in the 1980s series Robin of Sherwood, where Robin Hood is in thrall to (largely invented) Celtic god Herne the Hunter and encounters legends like the Seven Swords of Wayland and the pre-Christian deity Crom Cruach (who’s Irish; so he’s quite far from home in Sherwood). Stretching the point even further, we could even talk about Worzel Gummidge: a hit ‘70s and ‘80s kids’ series filmed around Hampshire farmland and villages, in which a slightly sinister “Crowman”, for reasons best known to himself, builds living scarecrows. Whether you’d class this as horror depends a great deal on your tolerance, as a child, for a show about a grotesque straw man that can remove his own head at will.

Children of the Stones (1978), about a village within a megalithic stone circle, has some overlap with The Owl Service in that it’s about events repeating themselves (and also in that it’s completely terrifying and supposed to be for kids); Doctor Who investigated The Daemons (archaeology, witchcraft and Morris Dancing in rural Wiltshire) and The Stones of Blood (druids and megaliths in Cornwall); and while it’s stretching a point to really call it horror, there’s a lot of black magic and dark folklore in the 1980s series Robin of Sherwood, where Robin Hood is in thrall to (largely invented) Celtic god Herne the Hunter and encounters legends like the Seven Swords of Wayland and the pre-Christian deity Crom Cruach (who’s Irish; so he’s quite far from home in Sherwood). Stretching the point even further, we could even talk about Worzel Gummidge: a hit ‘70s and ‘80s kids’ series filmed around Hampshire farmland and villages, in which a slightly sinister “Crowman”, for reasons best known to himself, builds living scarecrows. Whether you’d class this as horror depends a great deal on your tolerance, as a child, for a show about a grotesque straw man that can remove his own head at will.

In all of this, it’s the landscape that’s particularly important. Living in cities it’s easy to forget our psychogeographical underpinnings, but you don’t have to travel far outside of town to get back to the land that informs all these stories: there are still plenty of places where the stars aren’t obscured by street light sodium haze, and the shape of the moon dictates how light the lanes are at night. “The nooks and crannies of woodland,” Piers Haggard explained to Mark Gatiss for his BBC History of Horror, “the edges of fields, the ploughing, the labour, the sense of the soil, was something I tried to bring to The Blood on Satan’s Claw. We dug an awful lot of holes to put the camera in. It was important to me to have it often very low, to give you the feeling that we were somehow in the earth.”

The Borderlands meanwhile, while eventually shot near the Devonshire market town of Newton Abbot, was initially envisaged as a particular site on the desolate Dartmoor (also the home of The Hound of the Baskervilles). “It was originally supposed to be Brentor,” Elliot Goldner tells us, “which is a little church built on this sort of cliff edge in the middle of nowhere. You wonder how anyone ever got up there for ceremonies. Dartmoor is a magical place anyway: it has a very spiritual vibe about it. This church has lots of stories about the Devil visiting it and things like that. The West Country still has a “lost in the past-ness” about it. It’s amazing, but the problem with it was that it looks great from a distance but when you get up close it’s probably smaller than your kitchen!”

“I grew up in Essex next to some woods,” Ben Wheatley told Uncut this year, “and I had very vivid nightmares about the surrounding area. I’d have recurring dreams about a farm building that was near to us – and I still have them now. All the stuff that’s not mediated, that’s not about watching a film and being scared and incorporating it into your own imagination. For me, it was primal terror about the environment I lived in. I think over time that mutated into an interest in why the countryside is scary, or why England is scary.” Returning to those village Daemons and Stones of Blood, Wheatley will, tantalizingly, be directing the first two episodes of the next season of Dr Who (although he won’t have written them, so may be unable to indulge his preoccupations in that instance).

“I think A Field In England is very interesting in the way that it feels very claustrophobic,” Goldner says. “It doesn’t have any interior shots at all, but it feels like you might bang your head on the sky.”

The landscape, as Kim Newman pointed out in a recent Sight & Sound feature on A Field in England, is actually strangely unexploited in English horror cinema: we use it for history but not for the macabre. Your mind might switch immediately to all those Hammer sequences of horse-drawn coaches racing through woodland (usually the same woodland, in Black Park by Pinewood Studios), but it’s worth remembering that while they look for all the world like England, those films are supposed to be happening in Eastern Europe: Goldner jokes that they must therefore be volk-horror.

One late Hammer exception however, is Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter, which reverses the English-abroad trope by having a swashbuckling German blade tracking idiosyncratic aging-plague vampires in 17th-Century England, employing folk magic like burying toads at roadsides to track a vampire’s route. Its Buckinghamshire/Hertfordshire locations remain the same as ever though. Even for its Hound of the Baskervilles (another one rooted in invented legends) Hammer declined even to make the trek to Dartmoor and stayed in Surrey.

While we’re with Hammer, The Devil Rides Out, based on Dennis Wheatley’s occult novel, just about scrapes our folk list: its woodland cultists surprisingly echoed in Ben Wheatley’s Kill List more than four decades later. But it was rival studio Tigon that was irresponsible for The Blood on Satan’s Claw and Witchfinder General. Both are set at roughly the same time, but treat their historical subject very differently. Satan’s Claw aims explicitly at the supernatural, with the Devil beginning to manifest in another of those fields in England, and slowly strengthening his power by harvesting skin from the local youth, who have formed an impromptu cult.

Witchfinder meanwhile, is a more straight historical drama, interested in religious fanaticism rather than “real” witches. “Michael [Reeves, the director, who died tragically young soon afterwards] always said we were making a Western,” its star Ian Ogilvy told this writer recently. “It doesn’t look like it was made on a shoestring, but it wasn’t a terribly comfortable film to make. We were out in the wilds of Norfolk, and it was summer… but it was summer in Norfolk! It was bleak and brutal, although it wasn’t unremittingly gloomy in that Swedish way; there’s a lot of exciting stuff in it. Vincent [Price] was not happy. He was used to a nice comfortable studio!”

The Wicker Man is almost an imposter in the folk horror canon, since while it feels disturbingly authentic it’s almost entirely invented. On the surface it’s apparently Scottish rather than English, but it’s an outsider’s view of a mythical Scotland, written and directed by Englishmen and scored by an American. There aren’t even many accounts in history of wicker men genuinely being used for sacrificial burnings: Julius Caesar (but precisely none of his contemporaries) mentions in his 50BC Commentary on the Gallic War that the druids created wicker figures which “they fill with living men and, setting them on fire, the men are destroyed by the flames”; and a single 10th-Century manuscript describes similar events as sacrifices to Celtic thunder god Taranis.

Furthermore, Paul Giovanni’s music, though it feels traditional and “real”, is largely comprised of original compositions. British vocal ensemble the Mediaeval Baebes have often made a joke of incorporating the Summerisle song (“In the wood there grew a tree…”) into their medieval sets, despite its having been anachronistically written in 1973. But authentic or not, “the music was a big part of making the film seem otherly,” says Joel Morris of the indie folk band Candidate. “Folk music was something very unfashionable when I first saw the film. My only memory of folk music was probably the stuff in Bagpuss [another ‘70s British children’s TV series]. We knew the sound had a resonance: something alien and unfathomable. It’s like the music you’d hear at school assembly and be bored or amused by, yet in The Wicker Man it’s bawdy and vital. This safe music associated with scout camps and tweedy, beardy academics is suddenly a torrent of subversive, challenging filth!” Candidate went so far as to record an entire Wicker Man-inspired album (Nuada) and demo it at the film’s locations, again trying to soak up that psychogeographical vibe.

Music is important to Wheatley too. His Down Terrace features a folk-singing family with a constant undercurrent of simmering violence, while A Field In England’s soundtrack includes the traditional Baloo My Boy. “The idea is that the music in the first half is stuff they could play or sing themselves,” Wheatley told Uncut. But it also echoes Reeves’ vision of Witchfinder General as an English Civil War Western, in the introduction of “a Morricone twang”, in turn replaced by “full synth” as the characters begin to succumb to their psychedelic ordeal. “The music time travels,” says Wheatley. For the found-footage Borderlands, Goldner opted for practically no music at all, barring a densely creepy sound design that he likens almost to musique concrete.

It’s not just the music that’s evolving. Folk horror stories too are beginning to incorporate more modern elements. “We wanted Borderlands to be weirdness-in-the-West-Country,” says Goldner, “but we also didn’t want it to fall into that trap of local yokels… I wanted to show housing estates and kids wearing hoods and stuff like that, because I think that’s the thing: when you go to the British countryside now you can find beautiful spots, but equally you’ll find places that look like they’re inner-city. It all comes back to the title, The Borderlands, which again isn’t supposed to be something specific, but can refer to this strange hinterland where the countryside meets the town.” In this, it to some extent joins 2008’s Eden Lake, where kids in hoodies murder middle class intruders in the woods near housing estates in a savage satire of English Daily Mail attitudes. There’s also last year’s Citadel, which makes its hoodies into genuinely demonic homunculi. Our demons are changing form, but they remain folkloric constructions.

We also spill from housing estates to woods in Wheatley’s Kill List, but there are still more traditional examples of folk horror rearing their heads occasionally. The revivified Hammer’s Wake Wood, for example, gave us village life hiding dark secrets, while Robin Hardy has himself returned to Wicker Man territory with last year’s “spiritual sequel” The Wicker Tree (similar set-up, different victims). Hardy intends to complete his “Wicker Trilogy” with The Wrath of the Gods, exploring our Scandinavian folk heritage in Shetland.

Hammer too will be returning to the well soon, adapting Jeanette Winterson’s novel The Daylight Gate, dealing with the trials of the Pendle Witches in 1612. There is a future in England’s past yet.

****

*Please note an altered version of this article appeared on Fangoria.com.

WORZEL HOMAGE by Sproatly Smith on Mixcloud

FURTHER READING:

My Ian Ogilvy / Witchfinder interview:

http://creatureofthewheel.wordpress.com/2013/02/22/witchfinder-general/

My Joel Morris / Wicker Man interview:

http://creatureofthewheel.wordpress.com/2013/05/04/candidate/

Uncut Ben Wheatley interview:

http://www.uncut.co.uk/blog/the-view-from-here/the-blood-in-the-earth

October 19, 2013

October 19, 2013

hello.

9 yearss agoa fabulous article. really enjoyed reading and have just shared it on my Wyrd Britain facebook page.

https://www.facebook.com/Wyrd-Britain-831933380159997/

Thank you! I will pass it on the the author. I listen to your mixcloud mixes all the time

9 yearss agoHi Kier

9 yearss agothat’s cool to know

best wishes to you.

peace, ian