CLAP FOR THE WOLFMAN

“I’m runnin’ around naked in the studio right now, beatin’ my chest. And I wantcha to reach over to that radio, darlin’, right now, and grab my knobs. AAAOOOOOO!”

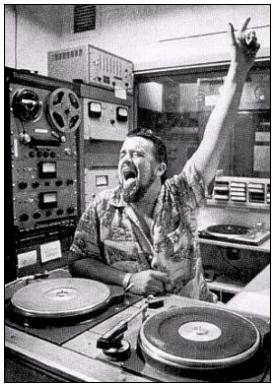

I can’t remember the first time I encountered Wolfman Jack; he was price check 50mg viagra just always a part of my life. But as a Canadian kid born in the early 70s, my experience of the notorious, gravelly-voiced deejay was as likely to have come from the tube as the radio. By the time I was five, the Wolfman was a ubiquitous presence on television, appearing in his own CBC variety show The Wolfman Jack Show at the same time that he was a regular host on The Midnight Special, recording albums, and doing a slew of TV guest spots, public appearances, revues and rock concerts all over the map. But while the alternately sweet and raucous sound of the Wolfman’s soulful jive first hooked many young 70s audiences via the power of television, an earlier generation – to quote ZZ Top – “Heard it on the X”.

“The X” is a reference to the call signs for Mexican radio stations (which all begin with the letters XE), in particular the “border blaster” stations that did not fall under American FCC viagra cheap fast shipping regulations and could thus broadcast at a much higher wattage, meaning a significantly more powerful reach. XERF in Ciudad Acuna – once the home of Wolfman Jack and likely the station referred to in the ZZ Top song – didn’t just reach across the border into the US, its signal stretched all the way to Soviet Russia.

In an attempt to control chaos on the airwaves, a North American treaty known as NARBA (established in 1941) set out an international band plan and interference rules for the US, Canada and Mexico which allowed for a certain wattage per capita – with the US more heavily urbanized, there were more radio stations, but transmitters were capped at a max of 50,000 watts. Whereas on the other side of the border, in Canada or Mexico, giant transmission towers were erected, giving a single station upwards of 250,000 watts of power.

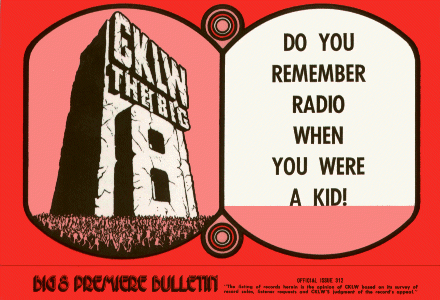

I grew up in Windsor, Ontario – a 10-minute walk over the Ambassador Bridge to the Detroit – which had a border blaster station of its own in the form of CKLW, otherwise known as “The Big 8”. Many of the charting acts that ‘broke’ in Detroit actually broke in Windsor, where music director Rosalie Trombley (“The Girl with the Golden Ear”) made CKLW the station that first championed many Motown acts as well as the MC5, Alice Cooper, The Stooges and more, a move that was quickly noticed and copied by those spinning platters not only in Detroit, but as far as Chicago. While the border stations would inevitably invite politically-motivated criticism and restrictive legislation that would see them flop or fold (see Michael McNamara’s incredible documentary Radio Revolution: The Rise and Fall of the Big 8 for more on what became of CKLW), the golden age of border radio was a beckoning wild west for adventurous deejays like Wolfman Jack.

I grew up in Windsor, Ontario – a 10-minute walk over the Ambassador Bridge to the Detroit – which had a border blaster station of its own in the form of CKLW, otherwise known as “The Big 8”. Many of the charting acts that ‘broke’ in Detroit actually broke in Windsor, where music director Rosalie Trombley (“The Girl with the Golden Ear”) made CKLW the station that first championed many Motown acts as well as the MC5, Alice Cooper, The Stooges and more, a move that was quickly noticed and copied by those spinning platters not only in Detroit, but as far as Chicago. While the border stations would inevitably invite politically-motivated criticism and restrictive legislation that would see them flop or fold (see Michael McNamara’s incredible documentary Radio Revolution: The Rise and Fall of the Big 8 for more on what became of CKLW), the golden age of border radio was a beckoning wild west for adventurous deejays like Wolfman Jack.

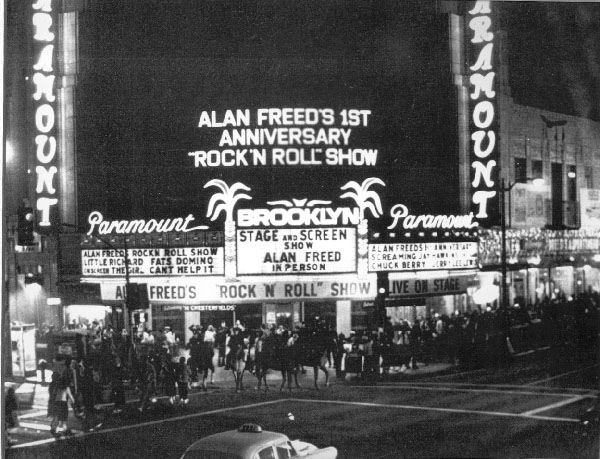

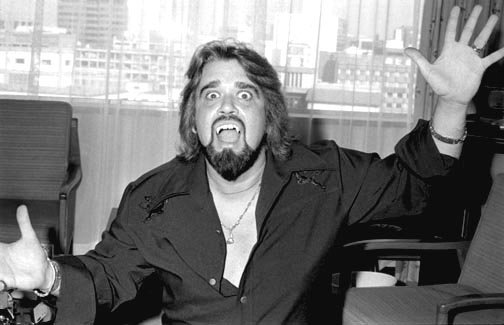

1950s broadcasting titan Alan “Moondog” Freed preceded Wolfman Jack in his influential championing of black R&B artists for integrated audiences – and similarly signaled the beginning of his radio show with a howl – but the persona of Wolfman Jack was perfectly aligned with the cartoonish era in which he rose to prominence. From the Moondog to The Hilarious House of Frightenstein, there seems to be a traditional association of werewolf and deejay, and Wolfman Jack remains its most compelling persona, complete with fangs, cape, lionesque mane, funky delivery, rhymes and alliterations – and an outlaw streak that was quintessentially rock n’ roll (although reading his autobiography made me realize what a G-rated version of Wolfman Jack trickled down to me as a kid).

The Wolfman began his life as Robert Weston Smith in 1938. Whole most sources list his birthplace as Brooklyn – to a poverty-stricken family where he was passed around between relatives – his 1995 autobiography Have Mercy! Confessions of the Original Rock n’ Roll Animal has him born in Manhattan to a family that had once bordered on millionaire status before the stock market crash of 1929 nearly wiped them out. In any case, they were still well off enough to have a maid, whom young Bobby adored and who moved with the family when they migrated Brooklyn a few years later. But following his parents’ messy divorce (in which they literally switched partners with a boozy swinging couple from the neighbourhood) he turned JD, found himself running with a gang called the Tigers, and the foundation for his record collection was laid by a fellow gang member named ‘Klepto’ who lived up to his nickname.

It was 1950 when he first heard the mysterious strains of XERF Radio coming in on the dial; their broadcasts came on at night, accompanied by the deep voice of Paul Kallinger – “Your good neighbour along the way from XERF, with 250,000 watts of power in Ciudad Acuna, Coahila, Mexico” – which at the time was full of product pitching, “wild-ass hillbilly music” and a marathon of evangelists who were as inspiring in their rhythmic patter as the deejays were. But it would be some time yet before XERF would become anything more to Bob Smith than a faraway signal on the radio.

In the meantime, like most teens, he was an acolyte of Alan Freed, first through The Moondog Show out of Cleveland, and later on New York’s WINS, through which Freed started hosted record-breaking rock n’ roll shows at Brooklyn’s Paramount Theatre in 1955. Already obsessed with radio, Smith found his way backstage and begged the Moondog for a job. But Freed told the kid to take a hike (unlike the leg up his onscreen counterpart gave to Moosie Drier’s pint-sized Buddy Holly fan in Floyd Mutrux’ American Hot Wax). But Smith persisted; he returned night after night and ingratiated himself with some of the other crew and backup performers, who eventually took him up as a kind of gopher. That is, until is parents found out he’d been sneaking out and he was grounded.

In the meantime, like most teens, he was an acolyte of Alan Freed, first through The Moondog Show out of Cleveland, and later on New York’s WINS, through which Freed started hosted record-breaking rock n’ roll shows at Brooklyn’s Paramount Theatre in 1955. Already obsessed with radio, Smith found his way backstage and begged the Moondog for a job. But Freed told the kid to take a hike (unlike the leg up his onscreen counterpart gave to Moosie Drier’s pint-sized Buddy Holly fan in Floyd Mutrux’ American Hot Wax). But Smith persisted; he returned night after night and ingratiated himself with some of the other crew and backup performers, who eventually took him up as a kind of gopher. That is, until is parents found out he’d been sneaking out and he was grounded.

Being separated from his calling led to a detour down the JD path again for a time, but when he started going to technical school in New Jersey, he found his way to WNJR in Newark, where he opted to skip class in favour of volunteering. He learned by shadowing the engineers, and aced his first shot at running the board when one of them called in sick. Unfortunately his parents were not as impressed as his employers; when they found out he’d been ditching school, they sent him away to boarding school, creating another setback in the Wolfman’s ascendancy.

Eventually he got kicked out of the house for good and found himself moving in with his sister’s family in Virginia, where he became a Fuller Brush salesman – a demanding door-to-door job that would instill some special huckster skills that would prove useful down the line. His brother-in-law was the first to recognize that Smith’s youthful restlessness was due to the fact that no one took his radio ambitions seriously, and that he was always being steered away from the one thing that had the ability to keep him focused and determined to succeed. And so Smith was registered as a student at the National Academy of Broadcasting, where he found he was the only kid whose goal was to work for an R&B station. Rock n’ roll was still considered a dangerous fad; if his colleagues expected a steady paycheck they were encouraged to aim for classical music stations.

His graduation demo saw him create the first in a long line of on-air personas – in this case ‘Daddy Jules’, which won him his first job working for a guy who’d bought up a small station (what the Wolfman called a ‘cripple’ station) after the war and reconfigured it to target black audiences, doing well enough with it that he was able to buy more stations and build the beginnings of an empire. He installed Smith at WYOU in Newport News, Virginia alongside a single co-worker, a black deejay named Tex Gathings who spoke with an ivy league accent himself, but gave Smith lessons in “jive diction” to develop his character. Meanwhile Smith supplemented his radio income by drug-running, low-level pimping (“brokering mattress action”, as he called it) and starting ‘The Daddy Jules Dance Party’ in one of the station’s unused studios, a daily afterschool dance party for teens. This led to him opening his own nightclub in Newport News called ‘The Tub’, catering to an integrated audience and selling moonshine out the back for regulars.

When WYOU’s top salesman bought his own station, a 250-watt “peanut whistle” station called KCIJ in Shreveport, Smith joined him, using the moniker as “Big Smith with the Records,” but was stuck doing gospel, country and facilitating redneck preachers. Worried that he was going to be relegated to hillbilly music forever, he turned again to his dream of working for XERF, that wild frontier power station broadcasting from over the border in Mexico. They too had their share of preachers, but they tended to be wild and crazy salesman types that Smith found entertaining – including the money-worshipping Reverend Frederick Eikentrotter, known as “Reverend Ike”, who encouraged listeners to “get out of the ghetto and into the get-mo!” It was there that he thought he could have total freedom to play obscure R&B tunes and to unleash the new ‘Wolfman Jack’ character he had been honing privately on the side.

The character of Wolfman Jack was a combination of things; his love of classic monster movies (aside from the big screen explosion of Cold War horror and sci-fi, the Universal monster films came to television in the late 50s, creating a generation of ‘Monster Kids’ and TV horror hosts), the undeniable influence of Alan Freed, the vocal mannerisms of comedian Lord Buckley and a wolfman character he used to scare his sister’s kids with when playing. The ‘Jack’ was simply beat jargon (“Hit the road, Jack”).

Aiding his confidence that this character could really take off at XERF was the belief that he could subsidize his own shows with a mail-order business just like the station’s flashy preachers did. Which leads us to exactly how what we know as “border radio” got started in the first place.

When radio first came into wide use in the 1920s, on air advertising was very frowned upon. Of the 526 stations that existed in 1924, over 400 of them refused to air any advertisements at all. By 1932 this was scrapped once the revenue potential was realized, which inevitably brought in regulation; the explosion of ads provoked the Senate to impose limitations on how much advertisement could feature on air, prompting the creation of the Federal Radio Commission in 1927, later to become the FCC in 1934. Critics of radio advertising warned against its use to defraud listeners, primarily though “quackery” – untested medical products, fortune-telling services etcetera.

A particular target in the case against quackery was one John Romulus Brinkley (1885-1942), known as the “goat-gland” doctor due to his claims that he could sexually rejuvenate impotent men by transplanting goat testicles into humans, who paid him handsomely for this service. And his primary means of advertising these services? Radio.

The entrepreneurial Brinkley inadvertently became an early radio pioneer, his attempts to circumvent FCC regulations leading to creation of the first “border blaster” station, XER-AM in Villa Acuna, Coahuila, Mexico (now called Ciudad Acuna), which was equipped with a then-unheard-of 50,000-watt transmitter. Despite his brilliant, Bugs Bunny-esque manner of constantly foiling the plans of the establishment types who would be his undoing, Brinkley was eventually felled by lawsuits from former “goat gland” patients that zapped his finances and shot his credibility when it came out that he wasn’t actually a real doctor. (To find out more about Brinkley check out Penny Lane’s brilliant 2016 documentary NUTS!)

With Brinkley’s empire falling apart, XER-AM (later XERA) was confiscated by the Mexican government in 1939 and sat vacant until 1947 when it reopened under new ownership as XERF. With the help of some American financiers, the station’s owners Arturo Gonzales and Ramon Bosquez formed a Texas-based corporation in 1959 with headquarters in Del Rio, just across the Rio Grande from Ciudad Acuna. While the license was officially to Bosquez who was a Mexican national, the station – its programming and finances – was actually controlled by the US-based corporation, and it was at this point that they increased to a 250,000 watt tower and became the true border blaster of legend. The US mailing address also explains why many people didn’t realize they were listening to broadcasts from Mexico. Other than some obligatory announcements in Spanish, the station was convincingly American.

When Bob Smith set his sights on XERF and went on a reconnaissance mission there in 1962 with KCIJ co-owner Lawrence Brandon and his new ‘Wolfman Jack’ demo tapes in hand, little did he know that he was walking right into the middle of an ownership dispute, which by extension had also become a labour dispute.

Now, Wolfman Jack has some crazy stories, but this one might just top the heap.

Apparently he and Brandon rolled into the station’s address in Del Rio hoping to pitch the station manager on giving the Wolfman a shot, and were directed to cross the border and drive out to the station itself. Once in Ciudad Acuna, most locals were unwilling to help them and insisted that there were no roads out to the station anyway. Which turned out to be true – it was literally in the middle of nowhere. Smelling some flush gringos, an old cab driver offered to chauffeur them out to the station for a hefty fee. While concerned that they’d be fleeced and stranded in the desert, they figured they didn’t have much choice; they didn’t drive all this way just to turn back when they were practically there.

True to his word, the driver got them there in one piece, but when they arrived, there was a heavy meeting going on, and the sole English speaker informed them that a shady deal had gone down in which the owner of the station, Arturo Gonzales, has engineered its confiscation by the Mexican government in order to implement a clause in his contracts with the various preachers who did business with XERF, allowing him to get out reciprocating on their million dollar lifetime ad purchases (thereby keeping the millions, without having to provide the air time – which meant the preachers had to eat the loss and keep paying if they wanted those ads running). But the result of this was the installation of an “interventor” named Montez, a government rep Gonzales had done a deal with on the side, to oversee the finances of the station. This guy turned out to be more crooked than Gonzales, and simply stopped paying the staff – creating an environment ripe for revolt.

The situation struck Smith as an incredible opportunity, and they offered to help the employees stage a coup, wherein they fortified the station with sandbags and barbed wire, armored everyone with illegal weapons and mounted an antiquated machine gun on the station’s rooftop as a very visible emblem of defiance. Smith then used his salesman skills to call up all the preachers and convince them that unless they paid the station’s “new owners”, their ads – which were really more like 15 to 30 minute fiery infomercials – would not air. Of course they were skeptical and initially refused. But when the usual timeslot rolled around, their tapes were not played. Instead, they were met with a gravelly howl, and the words: “Aaaoooooo! All right, baby. Have mercy! This is the Wolfman Jack Show, baby. We’re gonna par-ty tonight! We down here in Del Rio Texas, the land of the dun-keys!”

Finally convinced that whoever this mysterious stranger was must be telling the truth, the preachers started wiring cash to Del Rio, and with a matter of hours Smith had over $300,000 cash in the trunk of his car. The cash was used partially to bribe high-level Mexican officials to take the crooked interventor off the XERF gig and to give it to a rep of the union’s choosing, who would restore HR as well as the finances of the station. But Montez wasn’t about to let his piece of pie slip away without a fight.

“Thus began the Wolfman Jack Border Radio Shootout Saga” wrote Border Radio authors Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford, “a semi-apocryphal tradition, the true origins of which are forever lost in the hard, baked sands of the Coahuilan desert.” According to the Wolfman’s autobiography, not only was the station attacked by armed banditos twice, but the interventor Montez apparently showed up at the Wolfman’s hotel room in Del Rio, aiming to kill him. There is an official record of two shootouts at the station during that period, and at least anecdotal evidence of related fatalities that were covered up by the local authorities. But Wolfman Jack’s role as an instigator of these events is not corroborated anywhere, appearing only in his own (tall) tales.

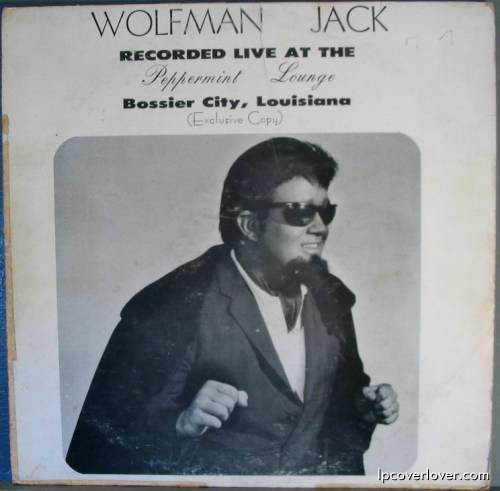

His famed tenure at XERF only lasted for 8 months (in person, anyway) – his income supplemented by selling Wolfman roach clips, a mysterious aphrodisiac called “Florex” (sugar-coated aspirin) and boxes of 100 baby chicks – before the unpredictable frontier life started to weigh on his duties as a husband and father. But returning to Louisiana, he came home from his first-ever personal appearance in Wolfman garb – at a gig to integrated audiences at the Peppermint Lounge (his first-ever public appearance as “Wolfman Jack”, which became his first record, “Live at the Peppermint Lounge”) – to find the local KKK burning a cross in his front yard. The Wolfman Jack Show continued on XERF through taped broadcasts, while he got the chance to run a “peanut whistle” of his own, KUXL up in Minneapolis. But The Wolfman Jack Show didn’t move with him; it stayed on XERF playing in pre-recorded form nightly from midnight to 4am, while in Minneapolis he maintained the persona of plain ol’ Bob Smith the businessman.

His famed tenure at XERF only lasted for 8 months (in person, anyway) – his income supplemented by selling Wolfman roach clips, a mysterious aphrodisiac called “Florex” (sugar-coated aspirin) and boxes of 100 baby chicks – before the unpredictable frontier life started to weigh on his duties as a husband and father. But returning to Louisiana, he came home from his first-ever personal appearance in Wolfman garb – at a gig to integrated audiences at the Peppermint Lounge (his first-ever public appearance as “Wolfman Jack”, which became his first record, “Live at the Peppermint Lounge”) – to find the local KKK burning a cross in his front yard. The Wolfman Jack Show continued on XERF through taped broadcasts, while he got the chance to run a “peanut whistle” of his own, KUXL up in Minneapolis. But The Wolfman Jack Show didn’t move with him; it stayed on XERF playing in pre-recorded form nightly from midnight to 4am, while in Minneapolis he maintained the persona of plain ol’ Bob Smith the businessman.

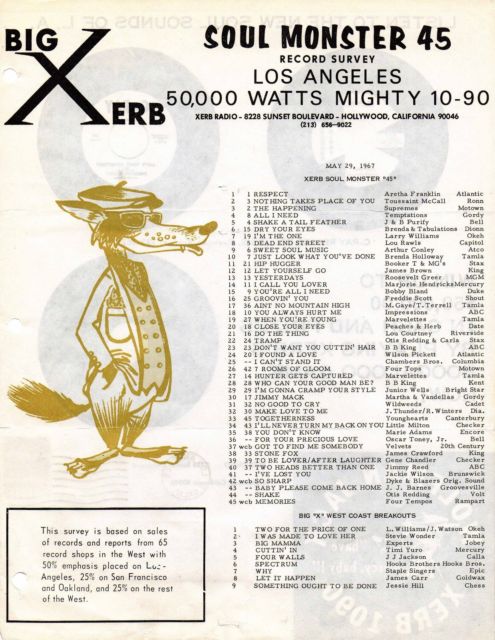

Of course, he missed doing the show live, and hooked up with the American ad rep for the border blaster stations and made a deal to take over operations and programming for XERB, a 50,000-watt station in Tijuana that – while considered the weakest signal of all the border stations – could be heard as far up as San Francisco. Smith knew how to turn around a station into a profit-making machine, and could be sneaky about it – he started by visiting the competition, a fellow R&B station in the LA area, posing as a potential ad client. He was given all their collected audience demographic data, which he then used tailor his own station to that audience. His plan was to make XERB seem like a local station, so in 1966 he set up a street-level office on the Sunset Strip with a bright neon XERB sign, and quickly won over the teen market, with kids of all shapes, sizes, colours and backgrounds tuning in to hear the wild man of the airwaves play music to get their blood pumping, their hearts heaving and their hormones racing. The station was soon making a profit of $50,000 a month – fueled primarily by strategically-placed sponsored evangelical timeslots – and that was after he’d paid out the owners their $30,000 monthly fee for the lease of the station.

Smith ran XERB until 1971, when the Mexican owners insisted that, as a Catholic country, the government would no longer allow the colourful variety of preachers to be given airtime on their station. As a result, the Wolfman had to cut loose 80% of the station’s revenue source, which meant he could no longer guarantee the steep monthly lease payments and had to rescind control of the station to its owners. Of course, it was all a ploy to get a bigger piece of what they now considered a cash cow – as soon Smith was ousted, the Mexican government suddenly had no problem with XERB’s moneyed, multi-faith advertisers. The owners tried to emulate Wolfman Jack’s programming, rebranding the station as XEPRS, “The Soul Express” but was never able to duplicate its success under the saavy watch of Bob Smith.

Smith ran XERB until 1971, when the Mexican owners insisted that, as a Catholic country, the government would no longer allow the colourful variety of preachers to be given airtime on their station. As a result, the Wolfman had to cut loose 80% of the station’s revenue source, which meant he could no longer guarantee the steep monthly lease payments and had to rescind control of the station to its owners. Of course, it was all a ploy to get a bigger piece of what they now considered a cash cow – as soon Smith was ousted, the Mexican government suddenly had no problem with XERB’s moneyed, multi-faith advertisers. The owners tried to emulate Wolfman Jack’s programming, rebranding the station as XEPRS, “The Soul Express” but was never able to duplicate its success under the saavy watch of Bob Smith.

With residual debts from the station (and the beginnings of a serious cocaine habit) he had to take a job at local station KDAY for a fraction of his previous salary. He started doing more appearances as Wolfman Jack, and selling tapes of his old XERB shows to other stations around the country, in an early form of syndication (in his autobiography he claims it was the first syndicated radio show, paving the way for others like Casey Kasem, but Alan Freed had been syndicated on over 40 stations back in the 1950s).

But the legacy of his time at XERB lived on; the border blaster had made an impression on a young George Lucas, who had been attending USC as a film student during Wolfman Jack’s reign. Lucas was fascinated by the mysterious Wolfman character, with his far out phrasing, raunchy humour and unrestrained declarations of love to the flummoxed teens who called into his show. “His voice would drift all over the west,” recalled producer Gary Kurtz in the book George Lucas: Interviews. “He would come and go over California with the whim of the weather. While you were listening, he would suddenly fade away; it was a strange ethereal feeling.” When Lucas started developing his 1973 coming of age film American Graffiti, he wrote Wolfman Jack into the script, with XERB broadcasts acting as the soundtrack to the film. “Wolfman Jack is the unseen center of it all,” wrote Michael Pye and Linda Miles, “father figure as much as circus master.” Though Wolfman Jack was cast as himself, it was fictionalized to a certain extent – the film is set in 1962 when Wolfman Jack was still on XERF, the station is depicted as broadcasting from within California, and his appearance is more polished than the wild and crazy fanged showman we would all come to know from his later live appearances. Though he had appeared as a live host of rock n’ roll revues throughout his days at XERB, and in a 1969 film of performances by improv troupe The Committee (featuring Howard Hesseman, who would later play a DJ not unlike Wolfman Jack on the TV show WKRP in Cincinatti) – it wasn’t until his prominently-billed role in American Graffiti that most of his listeners realized that Wolfman Jack was, in fact, white.

But the legacy of his time at XERB lived on; the border blaster had made an impression on a young George Lucas, who had been attending USC as a film student during Wolfman Jack’s reign. Lucas was fascinated by the mysterious Wolfman character, with his far out phrasing, raunchy humour and unrestrained declarations of love to the flummoxed teens who called into his show. “His voice would drift all over the west,” recalled producer Gary Kurtz in the book George Lucas: Interviews. “He would come and go over California with the whim of the weather. While you were listening, he would suddenly fade away; it was a strange ethereal feeling.” When Lucas started developing his 1973 coming of age film American Graffiti, he wrote Wolfman Jack into the script, with XERB broadcasts acting as the soundtrack to the film. “Wolfman Jack is the unseen center of it all,” wrote Michael Pye and Linda Miles, “father figure as much as circus master.” Though Wolfman Jack was cast as himself, it was fictionalized to a certain extent – the film is set in 1962 when Wolfman Jack was still on XERF, the station is depicted as broadcasting from within California, and his appearance is more polished than the wild and crazy fanged showman we would all come to know from his later live appearances. Though he had appeared as a live host of rock n’ roll revues throughout his days at XERB, and in a 1969 film of performances by improv troupe The Committee (featuring Howard Hesseman, who would later play a DJ not unlike Wolfman Jack on the TV show WKRP in Cincinatti) – it wasn’t until his prominently-billed role in American Graffiti that most of his listeners realized that Wolfman Jack was, in fact, white.

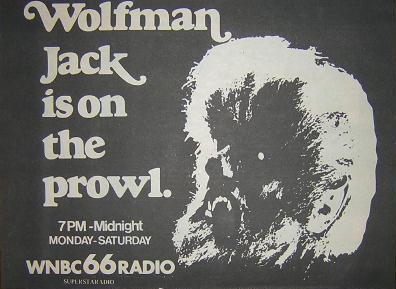

By this time, Wolfman Jack was becoming something of a cult icon; Todd Rundgren named a song after him on his 1972 album Something/Anything, The Grateful Dead referenced him in their 1972 song “Ramble On Rose” and in 1973 he began a 9-year run as co-host of NBC’s televised concert show The Midnight Special. At the same time, WNBC in New York gave him a $350,000 annual contract as a means of securing the #1 Top-40 spot against the formidable Cousin Brucie, who reigned supreme on competing station WABC. The Wolfman’s arrival in New York was heralded with a publicity stunt wherein a giant tombstone was cemented to the sidewalk outside WABC headquarters, bearing the words “Cousin Brucie’s days are numbered! Wolfman Jack is on the prowl.”

By this time, Wolfman Jack was becoming something of a cult icon; Todd Rundgren named a song after him on his 1972 album Something/Anything, The Grateful Dead referenced him in their 1972 song “Ramble On Rose” and in 1973 he began a 9-year run as co-host of NBC’s televised concert show The Midnight Special. At the same time, WNBC in New York gave him a $350,000 annual contract as a means of securing the #1 Top-40 spot against the formidable Cousin Brucie, who reigned supreme on competing station WABC. The Wolfman’s arrival in New York was heralded with a publicity stunt wherein a giant tombstone was cemented to the sidewalk outside WABC headquarters, bearing the words “Cousin Brucie’s days are numbered! Wolfman Jack is on the prowl.”

By the mid-70s, Wolfman Jack was a household name. When The Guess Who released their hit single “Clap for the Wolfman” in 1974, the Wolfman accompanied them on tour. Meanwhile he was recording albums of his own – Wolfman Jack (1972), Through the Ages (1973), Fun & Romance (1975) – guest-starring on television shows like The Odd Couple, Emergency! and What’s Happening, and was even attacked by wolves in a publicity stunt gone wrong somewhere in between. In 1976 the CBC debuted The Wolfman Jack Show, which was shot in Vancouver, requiring him to fly back and forth along the west coast for the year the show lasted, so that he could continue hosting The Midnight Special.

His movie credits also continued to pile up into the 80s, with roles in Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978), Hanging on a Star (1978), More American Graffiti (1979), Motel Hell (1980), The Midnight Hour (1985) and Mortuary Academy (1988), while more often than not he was cast as himself, on everything from Hollywood Squares to Battlestar Galactica. There was even a Wolfman Jack cartoon: Wolf Rock TV, produced by Dick Clark (whose company DIC had also made music-themed cartoon Kidd Video) and featuring the Wolfman as a mentor to a gang of kids who try to save a TV station in between live-action video segments. But it ran for less than two months in fall of 1984 before being cancelled.

Throughout the 80s the Wolfman continued to work as a deejay for KRLA in Pasadena (also the onetime home of The Real Don Steele – aka Screamin’ Steve from Rock n’ Roll High School), often lamenting the loss of the freewheeling radio format, when unknowns could press a record and bring it in to their local deejay. In 1995, a few months after his final guest-starring role on Married with Children, he published his autobiography Have Mercy! Confessions of the Original Rock n Roll Animal, and died of a heart attack less than a month after returning home to North Carolina from the book’s promotional tour.

While rock n’ roll radio has been host to some powerhouse talents over the years, there’s never been a deejay more famous than Wolfman Jack. And it’s unlikely we’ll see his kind again. But as the Wolfman said, radio signals never die, once they’re out there, they keep circling the cosmos, so maybe late one night you’ll tune into a mysterious station and hear a familiar howl…

++++

A mixtape tribute to the late, great deejay, performer and cult icon, Wolfman Jack. His wild and crazy persona was referenced in many songs (of all genres), as well as recording albums of his own. This mix features some of those songs by, about or referencing the legacy of the Wolfman, with snippets from his original radio shows.

FULL TRACK LISTING:

Todd Rundgren – Wolfman Jack | Wolfman Jack – Ain’t Never Seen a White Man | The Stampeders – Hit the Road, Jack | Sugarloaf – Don’t Call Us, We’ll call You | Wolfman Jack – Johnny do it Faster | Wolfman Jack – Gallop|Ramble on Rose – Grateful Dead | Whodini – The Haunted House of Rock | Wolfman Jack – The Blob | Tom Waits – Get Lost | Tammy Wynette – I’d like to see Jesus on the Midnight Special | Motel Hell excerpt | Wolfman Jack – Idol with the Golden Head | The Guess Who – Clap for the Wolfman | John Peel Remembers Wolfman Jack | Lucy Kaplansky – The Beauty Way | Wolfman Jack – There’s an Old Man in our Town | Wolfman Jack Signoff / Toussaint McCall – Nothing Takes the Place of You

++++

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Austen, Jake. TV-a-Go-Go: Rock on TV from American Bandstand to American Idol. Chicago Review Press, 2005.

Doyle, Jack. “Moondog Alan Freed” on Pop History Dig http://www.pophistorydig.com/topics/alan-freed-1951-1965/

Fatherley, Richard W. and David T. MacFarland. The Birth of Top 40 Radio: The Storz Stations’ Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. McFarland, 2013.

Fowler, Gene and Bill Crawford. Border Radio: Quacks, Yodelers, Pitchmen, Psychics and Other Amazing Broadcasters of the American Airwaves. Revised Edition. University of Texas Press, 2010.

Pye, Michael and Linda Miles “George Lucas” in George Lucas: Interviews. Sally Kline, ed. University Press of Mississippi, 1999

Sterling, Christopher H. ed. Encyclopedia of Radio. Routledge, 2004.

Wolfman Jack. Have Mercy! Confessions of the Original Rock n’ Roll Animal. Warner Books, 1995.

January 21, 2017

January 21, 2017

Comments