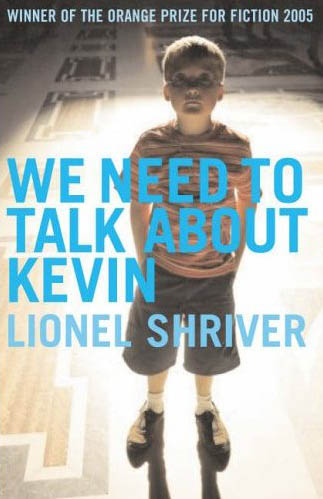

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT KEVIN

Lionel Shriver, 2003

(Serpents Tail edition, 2010)

With all the buzz surrounding Lynne Ramsay’s adaptation of Lionel Shriver’s award-winning book (which should hit theatres later this fall), Spectacular Optical decided to go back and take a look at the incendiary text that, for my money, is one of the most brave and honest depictions of the anxiety surrounding the decision to bring children into the world. The book’s subject and structure – a series of letters written by the mother of a high school mass murderer to her estranged husband, questioning her culpability in her son’s actions – demanded an immediate purchase (you can buy it HERE).

With all the buzz surrounding Lynne Ramsay’s adaptation of Lionel Shriver’s award-winning book (which should hit theatres later this fall), Spectacular Optical decided to go back and take a look at the incendiary text that, for my money, is one of the most brave and honest depictions of the anxiety surrounding the decision to bring children into the world. The book’s subject and structure – a series of letters written by the mother of a high school mass murderer to her estranged husband, questioning her culpability in her son’s actions – demanded an immediate purchase (you can buy it HERE).

Because of the structure as a series of letters – only her letters, we don’t get any sense of this being a reciprocal correspondence – it is Eva Khatchadourian, the killer’s mother, with whom we are led to align: a droll, bohemian entrepreneur with a successful series of travel guides that saw her traipsing all over the globe before being gripped by incongruous – and temporary – desire to have a child and become saddled to domestic space. But aligning with Eva is not always an easy task, as she is frequently condescending, pretentious and flippant about her situation. As she recounts the events of her life before and after the birth of the eponymous Kevin, we get a picture of a woman very much in love with her husband, in love with her jet-setting lifestyle, but perhaps a bit self-absorbed and judgmental to take the leap into motherhood. Even her portrayal of Franklin, the man she loves – if it can be trusted –depicts him as a blind fool whose personality is fundamentally at odds with her own. Although she romanticizes the ‘Way We Were’ melodrama of their differences – he’s a republican, she’s a democrat, he likes sports, she likes exotic textiles, he thinks their son is healthy and happy, she thinks their son is a violent sociopath – Kevin’s arrival drives an irreconcilable wedge between them, bolstering her resentment of their young son from day one.

One Thursday in April of 1999, three days before his 16th birthday, Kevin Khatchadourian beset upon nine hand-selected classmates and a doting teacher with a crossbow in an elaborately staged gymnasium massacre. In addition to the horror of having to assimilate the information that her son was responsible, Eva finds herself the target of a civil suit filed by the parents of the deceased, citing her poor mothering skills as nurturing Kevin’s antisocial behaviour, and thus indirectly responsible for his homicidal outburst.

Stoic and matter-of-fact on the stand, she is derided by the media as an ‘ice queen’, showing no more remorse than her boastful son, who emotionlessly pours over the minutiae of similar crimes that were frighteningly rampant at the time (Kevin’s rampage is set mere weeks before Columbine, which becomes a point of contention for the adulation-starved pubescent psycho).

The issue of remorse – not just remorse over a crime of this stature, but of the little crimes we commit every day in being unkind or behaving impetuously – is central to the book. Kevin’s lack of remorse is countered by his mother’s waffling burden of guilt – through her letters, she deconstructs the last 16 years in an honest, taboo-blasting series of diatribes in which she alternately claims to detest her own son and to tout him as a genius, the latter being his means of seeing through her by-the-book parental platitudes to detect her hatred of him. This blend of revulsion and respect keeps her and Kevin locked in an insular game of wits from which her husband Franklin is excluded (Kevin concocts a phony ‘Gee Dad!’ persona that is transparent to his eye-rolling mother, but Franklin gleefully buys into it).

There are moments when we question Eva’s version of events – after all, a mother who has so little empathy for her own son is societally unimaginable, sacreligious even (see the latest real-life media furor over Octomom’s open declaration that she ‘hates her kids and wishes she were dead’) and she does at times seem to truly have it in for him. When she finds him repeatedly masturbating with the door open, she is convinced it is so that he can involve her in his sexual fantasy life by forcing her to discover him mid-wank – which seems like a possible perverse projection. But Eva is recounting their chronology, bringing out all the warning signs that Franklin was so eager to ignore because it didn’t fit his American apple pie vision of familyhood.

There are also times – many times – when Eva’s narration becomes pretentious, preachy, self-righteous and kind of unbearable – but we can see her own defense system built up through all these things – a system that did most assuredly get handed down to Kevin, in perhaps more organized fashion. You see, her disdain for him aside, Kevin is in many ways like her – they are both cold, judgmental, smart, funny (when they want to be), and enchanted by the tangible bond of their game-playing. But it’s a game that each is determined to win – and strangely, each is trying to win the other’s love.

The book poses the question of nature versus nurture, and blame does get thrown around a lot here, but to answer this question plainly would be trite (as the movie version is, in my opinion). Eva discovers that our barriers are all social constructs – they are invisible lines and every once in a while someone realizes you can step over them – there’s nothing stopping you. Whether or not Eva is in fact a bad mother is also open to debate. She claims openly to be “terrible at it”, even though she goes through the motions unquestioningly (she goes to the PTA meetings dutifully), but she knows this does not make her a good mother. So then what does? This lack of conviction about her parenting abilities is something that Kevin picks up on and uses against her.

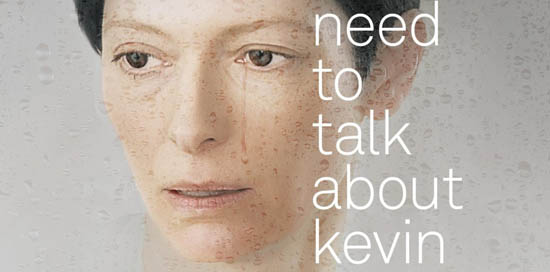

Lynne Ramsay’s film version is so condensed as to be emotionless (rather than just addressing emotionlessness), and the characters’ relationships lack the intensity with which their competition is played out in the book. A ready reading of the film suggests that Eva (Tilda Swinton) is suffering from guilt, but this is only one facet of Eva’s complex emotional response to the incident that Thursday; in the book, Eva feels more guilt about how her impetuous decision to have children against her better judgement damaged her relationship with her husband (John C. Reilly). I don’t think Eva ever feels strongly that she is responsible for Kevin’s actions. And Kevin himself is too likable and expresses too much pleasure in his bad behaviour, whereas in the book he is more of an inconspicuous blank slate (and the actor portraying him, Ezra Miller, is much too good looking). But the film doesn’t have time to really feel out these characters, at the expense of the audience. Lynne Ramsay’s disorienting, elegiac visuals are here (she is the director of Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar), but there is also nothing in the film that is devastating or horrifying; like Kevin’s actions, it is ultimately an empty act, meant to mean nothing.

The book has its flaws too, although they are minor: the level of narrative detail in the letters (long passages involving dialogue that don’t seem like the way things would be organized in a letter) sometimes pulls us out of believing the format is real, but overall, it’s a well-crafted mystery – for indeed, even though we know that Kevin is a mass murderer going in, it is still very much a mystery – and a tragic reflection empathy, remorse, accountability, our need to find fault somewhere, anywhere. There are big questions here, but there is also one hell of a story.

——————

– Kier-La Janisse

October 1, 2011

October 1, 2011  No Comments

No Comments