HITMAN HORROR

HITMAN HORROR: THE NEW BREED OF BRITISH EXECUTIONERS

Kier-La Janisse

——————

Before this past year, I wouldn’t have thought that ‘Hitman Horror’ qualified as a subgenre, but with two recent films – Sean Hogan’s The Devil’s Business and Ben Wheatley’s Kill List – emerging simultaneously from Britain’s indie genre scene, I’m tempted to reconsider. The UK has its share of influential cinematic hitmen, from Get Carter through The Krays and Sexy Beast, and as such Hogan’s and Wheatley’s films are fitting adjuncts to an esteemed tradition. But in these films, the added influence of supernatural horror proves an unbalancing element for characters whose profession calls for order and expediency, taking them to task for the lives they’ve led.

While very different films in both plotting and execution, their mutual disregard for crime genre conventions aligns them more with oddities like Stephen Frears’ The Hit (1984) – which critic Graham Fuller has likened to “a moral fable fraught with fatalism”- and the Nicolas Roeg/Donald Cammell film Performance, whose genre hybridity corresponds to its characters’ identity crises.

Following up on his downbeat crime comedy Down Terrace, and maintaining that film’s kitchen-sink aesthetic for much

of its duration, Ben Wheatley’s Kill List is about the complicated relationship between two hitmen who served together in Iraq, and the ethical discrepancies that buy levitra online us start to cloud their judgement and unravel their longtime friendship. The old adage “what do we do with our killers?” – a question that has been posed rigorously since the Vietnam War first openly addressed the perils of post-traumatic stress disorder – underlines the action in Kill List, whose protagonists Jay (Neil Maskell) and Gal (comedian Michael Smiley, returning to work with Wheatley from Down Terrace) seem unable to secure regular jobs since returning from the war. Instead, they are forced to earn money the only way they know how – through commissioned executions.

It is certainly post-traumatic stress that fuels Jay’s increasingly erratic behaviour, as well as the threat to his masculinity that accompanies not working. When the film opens, he hasn’t taken a job for 8 months, and his wife is at him about their depleted funds, which immediately characterizes him as a lazy, schlubby loser. But when he concedes and takes up a job with Gal, we are let in on why he’s been off work for so long: he’s a loose cannon. When they take the job, which should be ‘easy’ (three kills,

all domestic), Gal reprimands him for deviating from the kill list to messily wipe out a gang of kiddie-snuff traffickers connected to one of their targets (just as he would deviate from his wife’s grocery list earlier in the film, loading up on booze while skipping the toilet paper she had underlined as imperative) and reminds Jay that he doesn’t want a repeat of “what happened in Kiev”. We are never privy to what happened in Kiev, but can assume it refers to a job botched by Jay’s raging temper. Gal has his own issues – most notably an inability to reconcile his profession with his religious beliefs – but becomes a caretaker of sorts for his battle-scarred friend.

Despite its attention to the more banal elements of their domestic spaces and conversations, the world Wheatley’s brought us into is never quite ‘normal’ just by virtue of its protagonists’ profession. But things get really strange with the introduction of a religious conspiracy that leads I love this product and will buy it again. Http://www.fingermedia.tw/?p=1322774, our drugstore is committed to providing an affordable alternative to the high cost of drugs. Jay and Gal into murky supernatural terrain in which their proverbial hearts of darkness will be tested. Stylistically, Kill List’s horror precedents are homegrown; critics have been quick to point out its relationship to the British folk-horror of the 1970s (most notably Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man) in which natural spaces and foliage – benign enough on their own – become the signifiers of sinister cult activity.

Conversely, the setting of Sean Hogan’s The Devil’s Business is decidedly un-natural, its chiaroscuro lighting and coloured gels reaching toward foreign shores for its aesthetic influences, notably those of cinematographer Gordon Willis (best known for The Godfather trilogy and a decade of Woody Allen films) and Dario Argento (Suspiria and Phenomena in particular come to mind). Taking its title from a line uttered by Tex Watson at the Polanski/Tate residence during the

infamous massacre on August 8, 1969 (“I’m the Devil, I’m here to do the Devil’s business”), Hogan’s film is structured, nuanced, and deliberate, with a claustrophobic theatrical quality that likens it to a stage production – in particular a horror companion to Harold Pinter’s The Dumbwaiter (also an acknowledged influence on Martin McDonagh’s 2008 hitman film In Bruges). One location, two characters – one a tight-lipped veteran of the profession, the other his submissive but inquisitive rookie partner – and an assignment that will prove to be quite out of the ordinary.

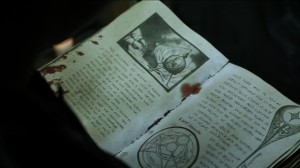

Pinner (Billy Clarke) is none too happy about being paired up with the newbie Cully (Jack Gordon), obviously a naive street thug who thinks that being a hired killer is an easy road to big money. Their assignment, handed down from the bald and bulky gangster Bruno (Harry Miller) is to wait for a former cohort named Kist to return home from a night at the opera so that he can get popped in the solitude of his own livingroom. As they wait, Cully is impatient and insists on filling the space between them with banal conversation, eventually prompting Pinner to shut him up with a story – a rather epic story about a bewitching stripper named Valentina who haunted her former workplace after Pinner was contracted to kill Compared to others on the market, best price and quality. Buy tadalafil we offer Canadian medications from a fully licensed Canadian mail order pharmacy. her. With the story suddenly interrupted by a noise outside, they venture to the back shed and find the bloody remnants of a black magic ceremony that leave them both seriously disturbed about just who it is they’ve been hired to kill.

Aside from their supernatural flourishes, the strongest tie between Kill List and The Devil’s Business lies in their emphasis on the fragile dynamic between two hitmen characters. Both revel in that curious blend of a ruthless profession with banal conversation that has become a staple of the contemporary gangster film, and much of their mutual tension is derived from the fear that one’s partner may not be reliable. It’s important to be professional in most jobs, but in this particular profession it seems especially pertinent for various reasons: expediency, cleanliness and the necessary grip on one’s emotions. Eschewing the stereotype of the hitman as a romantic lone wolf, these killers aren’t cool and self-sufficient like Bronson in The Mechanic or Michael Caine in Get Carter – they’re in over their heads.

Pinner is a man who has always followed orders, who has always gotten the job done and delivered on time. But this assignment really is the devil’s business, and no place for a hitman who doesn’t know when to walk away with his own skin intact. “This account has to be settled,” Pinner tells himself, not knowing whose soul is really on the line this time.

——————–

Interview:

SEAN HOGAN on THE DEVIL’S BUSINESS:

In what ways does the history of British hitman/crime films inform your own film?

Certainly The Hit by Stephen Frears, where you have a similarly fractious relationship between the older and younger killers, and in which a hit gradually spirals out of control and forces everyone involved to face up to how they’ve spent their lives. And then Performance to an extent – that whole 60s idea of mixing up the criminal underworld and mysticism, not that Performance really deals with that overtly, but it has a similarly weird feel and was definitely informed by that kind of decadent Crowleyan atmosphere. That path then leads you away from crime films towards something like Night of the Demon, which has its own kind of Crowley stand-in character in Professor Karswell, and who was certainly an antecedent for our own Mr Kist.

Your film has a theatrical or stage-like execution, with the one setting, two-character, dialogue-driven plot – was this just an economical consideration or were you deliberately channelling a theatrical atmosphere?

It was definitely an economic consideration to begin with. The initial idea for the film came about when I was waiting for the finance to come together for Little Deaths[i]. So I sat down and wrote it and showed it to producer Jen Handorf, who really responded to it. But then Little Deaths finally happened, so the script got put to one side. Fast forward a few months to when Little Deaths had turned into an absolute clusterfuck of a production, at which point Jen turned around to me and suggested it might benefit both our sanity if we raised a small amount of money and went and did our own thing.

So the small-scale theatrical approach kind of initially arose from that. However, I do think that sort of thing can work really well in horror movies – the claustrophobia, the slow burn atmosphere. I tend to like the idea of stripping everything down and just dealing with a few characters in a confined space no matter what size the budget is – early Polanski has always been a big influence on me in that sense. So the script was basically in my comfort zone anyway – we always said that we probably could have raised a bigger budget for it, but that would probably have meant compromising on certain things and giving up a lot of control, so we just embraced the down and dirty approach and went for it.

In particular it bears a lot of similarities to Harold Pinter’s The Dumbwaiter, not only for the reasons stated above but also in the particular dominant/submissive relationship between the two hitmen, and their relationship to the ‘higher powers’ in the film, as well as in the contrast between Pinner’s silence and Cully’s inquisitiveness and need to fill that silence with banal conversation, the fact that they are sitting in waiting for their target, right down to the fact that Cully’s trip to the bathroom is what essentially costs them their lives (his counterpart in The Dumbwaiter is described as constantly going to the bathroom) . Is this a coincidence or was The Dumbwaiter an influence?

Yeah, it was definitely an influence. Don’t ask me why, but my initial spark for the film was pretty much “a horror version of The Dumb Waiter”. The thing is though, I didn’t actually reread the play after that initial thought, it was just the idea of the two hitmen waiting for their victim to show up and then things turning weird that got me going. So it’s interesting when you bring up these other parallels. I definitely remembered the antagonistic relationship between the two killers and ran with that – I mean, if you’ve got two characters in a room and they’re not disagreeing about something then you don’t really have a scene! – and obviously the notion of them being completely at the mercy of these mysterious higher powers/dark forces came into play as well. But the thing about the bathroom I don’t remember at all – I’ll have to go back and look at the play again.

So much of the tension is derived from this contrast between the two characters and their respective ideas about what constitutes professionalism – what are the implications of professionalism in an assassin’s job compared to other types of jobs?

I guess I was interested in the idea of a character who’d obviously done terrible things – sometimes at great personal cost – and how someone would justify that to themselves. And there’s something very human about the kind of mindset that says “Well, I was just following orders and mine is not to question authority, etc etc.” It goes back to the Milgram experiment and that sort of thing. And that seemed to play very nicely into the Faustian aspects of the story – that this man had spent his life damning himself without really knowing it, but that he was finally going to be called to account. Beyond that, the notion of someone who was all about order and logic being forced to confront something that was completely irrational, and having his whole world pulled out from under him in the process, seemed to be interesting to me – I suppose you basically want to find different ways of putting characters through the wringer when you make these kind of films! Essentially, the whole film is a journey by which Pinner is forced to face up to the choices he’s made in life – to the point where he could probably get away from the house at the end, but chooses instead to go back inside and try and see the job through, and by doing so is well aware that he’s essentially committing suicide.

Why do you think hitmen make such compelling characters?

I’m not sure – there might be something in the idea that characters who live extreme lives are usually interesting to follow, and what can be more extreme than making a living from killing other people? There’s also the moral issues involved – as a writer, you often tend to look for the sort of characters who are on a moral cusp, just because that makes for good drama, and hitmen obviously lend themselves to that – I guess that’s why you tend to get a lot of films about assassins doing “one last job”. And needless to say, being a hitman is usually going to involve violence along the line somewhere, which is often the meat and potatoes of cinema. But I think it’s just an interesting archetype – if you’re drawn to writing about antiheroes, there’s a lot of dramatic mileage in looking at someone who kills simply for money rather than for reasons of insanity or whatever.

Why do you think there are suddenly two hitman-horror films in the same year, coming from the same country , and both dealing to a certain extent with devil worship? Do you think there are any social/cultural developments in Britain that would have subconsciously led to this?

I don’t know – you can imagine how worried we were when we read about Kill List going into production! We actually met Ben Wheatley and his producer when we were at SXSW with Little Deaths and they assured us that Kill List was very different to how it sounded on paper, which happily turned out to be the case.

So the two films are ultimately quite dissimilar, but I guess what they have in common is the idea of using the idea of the hitman as something symptomatic of the human need to follow orders and the ways in which we can justify the most appalling actions to ourselves. In Kill List the protagonist announces that their intended list of victims all “deserve to suffer” – but of course, that’s not the reason why he took the job on in the first place. In our film, Pinner’s way of dealing with what he does is to subsume himself utterly to his job and disavow all personal responsibility – and history has shown us exactly what can result from people doing that. So both films end up with their lead characters in some pretty damned places, in one way or another. Maybe there’s just something in the air at the moment – a real distrust of authority and the establishment – and so these kinds of stories are in some way a reaction to that, a way of looking at what happens when people do terrible things in the name of money or authority or whatever.

Your film is highly stylized – at one point the camera is fixed on Pinner in a way that looks like the camera is attached to him (as in Gerald Kargl’s Angst) so that it is fixed while he is moving (I’m not a filmmaker so I don’t know what this technique is called!), the lighting uses the coloured gels characteristic of Italian cinema and a lot of very deliberate obscurity and blackness, while the dialogue is very emphatic and literary at times. Can you tell me a bit about your ideas for what you wanted to do stylistically to marry supernatural horror and crime in such a unique way?

That particular bit of kit is called a snorricam – the first time I remember seeing it was in Mean Streets. But yes – the problem with a film like this is how to keep it visually interesting. We had very little time (it was shot in 9-10 days), money or equipment, so whereas I normally like to try and move the camera a fair amount, it was tricky to do under these kind of shooting conditions.

So I just tried to keep it as visually alive as possible. Luckily we had a very good DP in Nicola Marsh, who really embraced the kind of thing I wanted to do – as you say, the coloured lighting is a product of watching a lot of Bava and Argento, and aside from that, I wanted to keep the feel very dark overall – very Gordon Willis, basically. I was definitely interested in the idea of taking a noir-ish approach to the look, especially given the crime element, but then adding some stylised colours and angles into the mix.

And using little things like the snorricam helps to break it up slightly as well – a lot of scenes are shot quite simply, but every now and then you throw in something like that and it just helps juice up the visuals a bit and give it a slightly weirder feel. I’m not a great fan of shooting handheld, but given the tight schedule we were on, we decided to go with it to an extent. But what we did was generally only shoot handheld after a certain point in the story – everything is quite controlled up to where they carry out the contract, and then when they return to the house after that it’s largely handheld, as if to reflect their world spinning off kilter.

A big part of the film is Pinner’s story about the dancer Valentina. It’s like time stops, so that this story can unfold, sort of like Quint’s story of the USS Indianapolis in Jaws or Karloff’s recitation of ‘The Appointment in Samarra’ in Targets. Like those moments in those films, I think this story – its placement and delivery, are a major part of getting the audience to really sink into the film. Can you talk about its conception?

Yeah, that scene was one of the major things that I suspect we would have had real problems with had we tried to access bigger sources of funding. “It’s just a guy talking for 5 pages, cut it out!” But again, it came about very organically. I had it in my head that I wanted one guy to tell the other a story, and knew that this story was going to have to feed into the main narrative somehow, but beyond that it was pretty vague. It all could have fallen really flat had we not found an actor who could pull it off. Again, that was part of the challenge. I remember promising Billy that we’d push it back in the schedule so that he had time to prepare, and that we’d shoot plenty of coverage etc – and then he sailed right through the whole thing on the first take. Cue round of applause from the crew! And even then, I still wasn’t sure whether it was going to play for an audience or not, but when the first people to see it all said how much they liked that scene, I figured we’d got away with it. Because as you say, those kind of scenes can be absolutely spellbinding when they work. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve watched Quint’s monologue in Jaws – I’ll often just put on that scene alone. So having grown up loving that, I guess I’m perfectly happy to sit and watch someone deliver a long monologue onscreen. That might not be the norm these days, but what the hell.

The two most important questions I almost forgot to ask you: 1) Do you believe that wombles are real? 2) What song, out of any song in the world, do you secretly wish was written about you?

Oh, why do you do this to me..?

1) Yes – I owned one when I was a kid. He talked and everything.

2) Not sure there’s any way to answer this question without sounding like a total asshole! But I’ll say The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me) by Tom Waits, although it’s less a case of wishing it had been written about me than it sounding like it was…

February 2, 2012

February 2, 2012  No Comments

No Comments