THE BLACK POWER MIXTAPE: 1967-1975

THE BLACK POWER MIXTAPE: 1967-1975

THE BLACK POWER MIXTAPE: 1967-1975

Kier-La Janisse

Goran Hugo Olsson talks about his groundbreaking bibliodoc on the American Black Power Movement, fashioned from hundreds of Swedish news specials

————————-

Edited by Swedish filmmaker Goran Hugo Olsson from footage originally shot by Swedish journalists visiting America in the 1960s and 70s, Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 is a veritable treasure trove of unseen footage of that revolutionary period, full of remarkable interviews that give Black Power leaders the voice they never had in mainstream American media at the time. The film is essentially a bibliodoc – using all previously existing footage, the only newly-created material consisting of the dense soundscape from Ahmir Khalib Thompson (Questlove of The Roots) and Om’Mas Kith (of hip hop group Sa-Ra) and insightful offscreen voiceover commentary from Erykah Badu, Harry Belafonte, Talib Kweli, Melvin Van Peebles, Angela Davis and more, from a contemporary perspective. But Olsson’s astute editing provides additional urgency and resonance to the interview footage to show how the ideas parlayed by the leaders of the Black Power movement rippled out into the community in ways that changed the game forever.

The film begins as the civil rights movement shifts into the Black Power Movement in the mid-60s[i] and focuses largely on the development of the Black Panther Party and the continuing influence of The Nation of Islam. While these are only two of the most cohesive rallying points for the Black Power Movement, there were individual actions (Angela Davis, one of the most influential Black Power leaders, was never a card-carrying member of the Black Panther Party), as well as violent actions by the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Negative aspects of the Black Power Movement – violence between members, the ‘terrorist’ actions of the BLA, rumours of drug-dealing and extortion in the ranks of the Panthers – are not given much, if any screentime.

The film begins as the civil rights movement shifts into the Black Power Movement in the mid-60s[i] and focuses largely on the development of the Black Panther Party and the continuing influence of The Nation of Islam. While these are only two of the most cohesive rallying points for the Black Power Movement, there were individual actions (Angela Davis, one of the most influential Black Power leaders, was never a card-carrying member of the Black Panther Party), as well as violent actions by the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Negative aspects of the Black Power Movement – violence between members, the ‘terrorist’ actions of the BLA, rumours of drug-dealing and extortion in the ranks of the Panthers – are not given much, if any screentime.

But the film is not meant, in itself, to criticize its subjects; it is a platform for its subjects to be critical. These are perhaps growing pains of any revolutionary movement – some members grow impatient and act out with the aim of hurting their oppressors since they can’t make them understand what’s wrong with the bigger picture. As Angela Davis points out in the film’s archival footage, she was surrounded by violence growing up: bombs exploding, guns firing; these were the weapons of racists who were discriminating against the Black families in her neighbourhood. But suddenly if a Black man has a gun this is perceived as having significantly more violent potential than a white man with a gun. The white establishment’s fear of this image – that of an armed Black Man – ensured that it would become one of the central images of the Movement, creating an aesthetic that was impossible to ignore. As Amy Abugo Ongiri writes: “In challenging the ways in which politics can and should engage with culture and art in the U.S. context, the Black Power and Black Arts movements undeniably shaped wider cultural perceptions of what it means to be African American, what it means to engage in social protest, and the interface between identity and political action.”[ii]

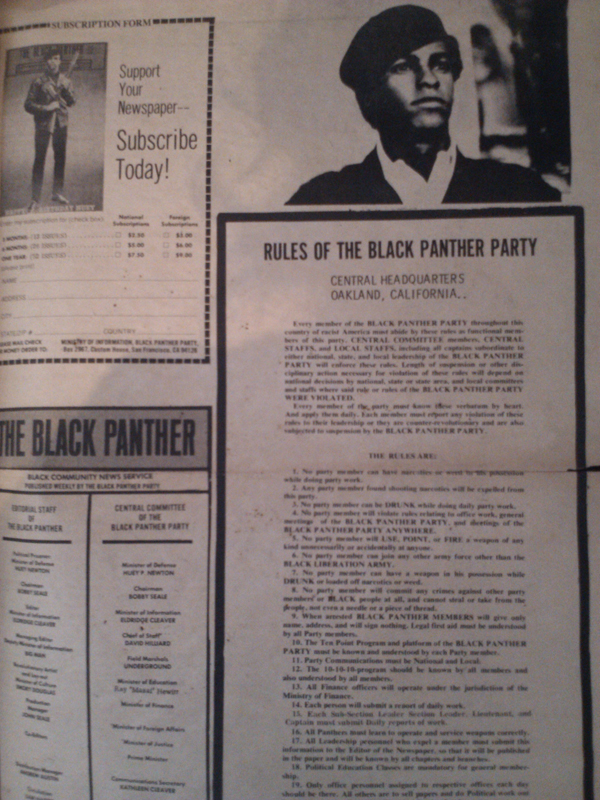

Guns, and the petitioning of rights to firearm access, was one of the primary (and controversial) elements of the Black Panther Party’s mandate. Originally called “The Black Panther Party for Self Defense”, it ran from 1966-1982, founded in Oakland, CA by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, who were inspired by the writings of Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X’s call to action “by any means necessary”. Through their newspaper The Black Panther – which had 250,000 subscribers at its height – they published their 10-point platform to guide the black people to determine their own destiny and to see their communities empowered. The right to peace, food, shelter, employment and quality of life free from racism. But it wasn’t all about militance. Revolution, as Angela Davis points out, while often accompanied by violence, has many other elements that are non-violent. The Black Panthers’ free breakfast program[iii], clothing distribution, first aid and educational centers were an equally important part of the revolution. Creating a healthy community, physically, emotionally and intellectually. And their work was not limited to the Black community, as they frequently partnered with other groups (such as Latino group The Young Lords and Appalachian group The Young Patriots) to make sure that a number of other visible or ideological minorities received the same attention.

Of course, their efforts were not appreciated by the existing authorities, with FBI head J. Edgar Hoover declaring the Black Panther Party “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”[iv] and creating a special program (called COINTELPRO) designed to eradicate it and other internal radical organizations, through often illegal methods including surveillance, infiltration, police harassment, depletion of its resources through false charges, and even assassination. The party faced numerous charges against its members and leaders that saw them successively incarcerated, thereby weakening the core of the group. Initially one of the 8 people charged with conspiracy and inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, Panther Bobby Seale was tried separately (thus “The Chicago Seven”), largely because evidence linking him to the case was especially weak. But he still received a four-year sentence, and was bound and gagged in court because of his outbursts – which would become an indelible image for the raging counterculture, later referenced in songs by Graham Nash and Gil Scott-Heron as well as played out in Peter Watkins’ harrowing docu-drama Punishment Park.

How to deal with the problem of the white establishment’s organized aggression was a source of fierce debate within the movement; with the incarceration of many of its important leaders, Huey P Newton was confident that new leaders would rise up their place, but it just didn’t happen. The growing consensus that the government was poised to do anything to keep the black revolution down caused an increase of support for the more radical Black Liberation Army (BLA), a Soviet-supported nationalist group that engaged in what would typically be described as terrorist activities, not unlike those of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, the Symbionese Liberation Army or the Weathermen. (Although BLA member Assata Shakur has stated that the BLA was not an organized group with a hierarchy but a network of independent cells fighting for the same goal).[v]

As pointed out in Olsson’s film, the response to the waning leadership of the Black Panther Party was a turn to the Nation of Islam, the African-American religious movement founded in the 1930s, whose famous members have included Malcolm X, Muhammed Ali and Snoop Dogg. The NOI was positive, if more austere influence on the community, which by the mid-70s was starting to suffer from major addiction issues (which some infer was part of a conspiratorial effort by the government to cripple the movement). As a busload of Swedish tourists passes through a Harlem neighbourhood (and past a movie marquee for The Cut-Throats Nine!) in 1974, their tour guide declares “Large amounts of heroin are circulating in Harlem…You might have read in our welcome letter that we do not want anyone to visit Harlem for personal studies. That is because this neighbourhood is only for coloured people. Not even the ‘better’ – if I may use that word – not even the ‘better’ coloured people visit this area because of the risk of being mugged.” A local cop trawling the neighbourhood concurs: “Well this block is business as usual,” he says. “Instead of a hundred junkies out today, there must be a thousand.” When an overdosed Black man is taken away in an ambulance, someone in the crowd yells out “OD – one less!”

Among the film’s many interviewees are Louis Farrakhan, national spokesman for Elijah Muhammad of The Nation of Islam (and who would succeed him in 1975, a year after this footage was shot), and as USC professor Robin Kelley points out in voice-over, Farrakhan was trying to clean up the image of the Nation of Islam, which had degraded into one of corruption, internal violence and assassinations – as Kelley puts it, “thuggery”. But he’s still a preacher, and he talks like a preacher, laying down commandments that sound no different from those shady preachers who would become a source of parody in so many blaxploitation films of the era (Ossie Davis’ Cotton Comes to Harlem, based on the novel by Chester Himes, comes to mind). But with the movement falling into disarray, Farrakhan’s message was a much-needed one. “There’s a generation of people who are seeking precisely that kind of discipline,” says Kelley, “because the drugs are taking over. The mid-70s is the period of the beginning of the decline.”

Director Goran Hugo Olsson was kind enough to answer a few questions about fashioning such a groundbreaking work from an outsider’s perspective – geographically, racially and temporally.

—————————

First, tell me about where this footage was found, and what it was originally used for? Were there news specials made up of this footage? Was the footage all focused on the Black Power movement, or was that just the footage you culled for your project?

The footage originates from hundreds of different sources. The most parts are from television documentaries, another huge part from “60-minutes”-like inserts and the rest from news inserts. Everything did not evolve around the term Black Power, but a great deal of it. This term, was mentioned all through this period in the same way as the Civil-rights movement, as something the audience could relate to. Everything was shown prime-time on national broadcast, but only once – not to been seen again.

Do you know anything about the people who originally shot it? Were they from a countercultural background, or already sympathetic to the Black Power movement before shooting?

I know several of those filmmakers and reporters. I think at least a ten of them were present at the Swedish opening. I think you could divide them into two categories: first, young filmmakers sympathetic to the cause in North America, and those fueled by the injustices of the war in Vietnam in a global struggle for better world.

Where did your own interest in black revolutionary subject matter come from?

I think my interest is not primarily color, but injustices. And of course being unfair because of such superficial things as skin color or gender is the most disturbing form of injustice. However I vividly remember something in me changed when I returned to school in the fall of 1976. Being ten years old and learning about how the apartheid police killed kids, not just older students, for demonstrating in Soweto was life-changing for me. After this, we dedicated a day every year to raising money for the ANC. Today it seems like rather innocent thing to do, but at the time ANC was an armed guerrilla movement, and had nothing of the later Mandela glory.

What is the situation for black people in Sweden? How many black people live there?

No idea [how many]. But the few we had then were either Americans escaping the Vietnam war deflecting from Germany to neutral Sweden. Or jazz musicians drifting from Paris. Sometimes they were both, like Albert Ayler, who played with Coltrane. Now we have a lot of immigrants from Africa, like Somalis and Sudanese. The ethnic problem in Sweden, on national level, lays in the tension between “swedes” and “immigrants/muslims”. But on a personal level people who look of African descent face daily discrimination and often harassment.

In light of your own interest in this subject matter, what do you think of Courtney Callender’s comments in the film about white people’s interest in black issues as inherently racist, because it posits black people as something exotic or separate?

I think Callender’s comments are very important, as-well as Erykah Badu’s comments on the same topic. My film – and this is so important to point out – is not a film about the Black peoples’ struggle in America or the Afro-American community. I could never make such a film. Someone with the American experience, from that community has to tell that story. My film is about how Sweden looked upon these issues at the time. I could do that, because I found the stuff, in my hometown; these reels carry my history as well. And I do hope someone in the future should take my film and re-edit in different way. That said, I also think that the post-slavery situation in North America (not just the US) is one of those stories that we have to tell over and over again, like that of the Holocaust or colonization. New generations find new ways to tell the same story.

What is the difference between the glorified “terrorist-chic” version of the Black Panthers and their real community efforts? How much was a military image important to what the Black Panthers were doing?

I think that the Black Panthers are largely misinterpreted. If you look at the community programs, or their ten-point program, most people would agree. The mandate read aloud to state parliament in Sacramento[vi] was also very important, stating that all Americans had the same rights – in this case carrying firearms. And it kick-started the movement. But given the circumstances it gave the police a pseudo-reason to hunt them down. Sometimes I get the feeling that people today mix up the Panthers with the BLA, which was more like the 70s terrorists we saw in Europe.

What was the role of the Nation of Islam at the height of the Black Panther Party? It seems from the structure of the film, that the community energy that was poured into the Black Panthers was redirected to a resurgent interest in the Nation of Islam in the mid to late 70s, and that a lot of it was tied to the proliferation of lethal drugs in the community. Is my interpretation accurate?

Correct. And again, this is not for me to tell. But in a very general and brief way I guess you could say that the Black Power Movement and the Black Panthers got momentum from both Malcolm X and Dr King. And when that faded, the energy went into all kinds of directions, one of them being The Nation of Islam.

What is that footage of the helicopters crashing into the water and being thrown from a ship into the water?

When the Americans left Vietnam and Hanoi they airlifted people out from the roof of the embassy. And they had more helicopters than they had space on the hangar-ship. To me this was the ultimate image of the waste of resources in this war. Pushing helicopters into the ocean.

Tell me about the amazing sound design and soundtrack – it seems like there are a few things layered – like when a cassette tape gets old and sound from one side starts leaking into the other. It’s very ominous.

Thank you. I think we ended up using more than 15 different songs, but we worked with them as a score. I’m so happy that Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson and Om’Mas Keith took the time to make this fantastic music. Due to complicated rights issues it is not available commercially, but I heard that you could find it Soundcloud. A lot of people have asked for it.

BLACK POWER MIXTAPE 1967-1975 screens as part of CINEMAPOLITICA on Monday February 6th at 7pm, introduced by writer and community activist David Austin. Room H-110 Concordia University, suggested donation $2-$5.

[i] Even the fact that I’m inclined to capitalize ‘Black Power Movement’ and not the civil rights movement shows the authority that the term carried.

[ii] Ongiri, Amy Abugo. Spectacular Blackness: The Cultural Politics of the Black Power Movement and the Search for a Black Aesthetic. University of Virginia Press, 2010. Pg. 18

[iii] In The Black Panther Oct 11, 1969 issue, Chicago BP chapter member Sister Beverlina writes in refuting claims by the mainstream press that the Panthers in Chicago were no longer serving free breakfast. “The article also stated that the Party was using the Breakfast money and food for their own personal use. This is totally incorrect, the Black Panther Party refuses to accept the ideology of the capitalist pig power structure which starves 70% of its population and uses food funds to send their astro-pigs to the moon for the purpose of “heightening exploitation”.” (a sentiment echoed in Gil Scott-Heron’s “Whitey on the Moon”)

[iv] Qtd. Stohl, Michael. The Politics of Terrorism CRC Press. Page 249

[v] The leaderless resistance group The Animal Liberation Front – which uses a similar militaristic aesthetic to inspire terror – has been operating by this method since 1976.

[vi] On May 2, 1967, thirty Black Panthers dressed in black leather jackets, black berets and dark glasses (and armed with shotguns) approached the capitol building where then-governor Ronald Reagan was speaking to some schoolchildren. After Bobby Seale read aloud their organizational mandate calling for the end to oppression of Black people in America they proceeded into the building to protest the selective ban on firearms, creating a media frenzy.

February 2, 2012

February 2, 2012  No Comments

No Comments