FULL MOON SWANBERG

FULL MOON SWANBERG

Joe Swanberg discusses Silver Bullets as well as the recent intersections between genre and mumblecore filmmaking

By Ariel Esteban Cayer

——–

Joe Swanberg, who was instrumental in defining the “mumblecore” movement with Kissing on the Mouth in 2005 has been exceptionally prolific in the last year, even for a filmmaker known to release at least 2 films annually: Uncle Kent premiered at Sundance 2011, quickly followed by both Silver Bullets and Art History in Berlin, The Zone at AFI Fest and Caitlin Plays Herself at Brooklyn’s reRun theater in December. Amongst them, Silver Bullets stood out for genre audiences as the particularly intriguing one, with its alluring promise of lycanthropy and potential horror, which, for those following the director’s career in the last year or so, isn’t entirely surprising. Indeed, in addition to starring in his aforementioned film, 2011 also saw Swanberg embark on a wildly fruitful collaboration with new horror wunderkind Adam Wingard, to whom the Fantasia Film Festival dedicated a mini-retrospective to in its past edition, screening Pop Skull, as well as A Horrible Way to Die (2010) and What Fun We Were Having: Four Stories About Date Rape, the latter two of which Swanberg stars in.

In Silver Bullets, starring director Ti West (festival hits The House of the Devil, The Innkeepers), Larry Fessenden (briefly), Swanberg’s series of highly reflexive films about the creative process finds its “horror” incarnation. About the processes of making films, both horror or otherwise and about the impact it can have on one’s relationships, Silver Bullets follows Claire (Kate Lyn Sheil, destined to great things and also appearing in Wingard’s upcoming You’re Next), a young actress intimately involved with director Ethan (Swanberg). While finishing a project together, she accepts a role in a werewolf film to be directed by successful up-and-comer Ben (Ti West, virtually playing himself), which considerably strains her relationship with self-questioning Ethan, who imminently gets back at Claire by casting her best friend in the lead role of his new film. Beautiful deconstruction of the creative process and yet another intimate look at relationships from a director that has more than honed his craft with this specific subject matter, Silver Bullets finds Swanberg working in an increasingly formalist style – which is far removed from the handheld shenanigans of earlier “mumblecore” work – to produce a great documentation of the struggles of legitimizing one’s existence through cinema. Entirely improvised, Silver Bullets most importantly asks some very touching questions: as cinephiles or filmmakers, is our passion for film – and this obsession we seem to share of wanting to express, record or live life vicariously through moving images – worth the trouble? Is it worth the time, lost friendships and heartache of broken relationships? Is there a healthy way of balancing things out? Swanberg’s moving self-“horror” effort might not entirely answer these questions, but definitely invites self-examination.

The following interview discusses Swanberg’s recent intersections with genre films, his collaborative process as well the making of Silver Bullets, which screens March 1st at Montreal’s Psychotronic Film Centre Blue Sunshine at 8pm (3660, Boul. St-Laurent, 3rd Floor).

AEC: In Silver Bullets, you create a drama of relationships around two competing directors but also two dissimilar and contrasting film genres. Why choose horror as the mirror image of your character Ethan’s more overtly introspective and intimate style of filmmaking?

JS: I’m very jealous of horror filmmakers because the fan base is so involved. It’s frustrating to spend so much time and energy making art films that appeal to such a small, often aloof, cinephile community. I wanted my character in Silver Bullets to adopt a snobby attitude toward the horror film that his girlfriend is making, but to also realize that the horror film, whether it’s good or bad, will be seen by more people than his own work and will be cared about by more people.

AEC: How did you become involved with Ti West and Larry Fessenden for the making of this film? Can you talk a bit about its inception and production?

JS: I met Ti in 2005 when we both had our first films at SXSW. I was there with Kissing on the Mouth and he was showing The Roost. We stayed in touch via email and AIM for the next few years and we both had films at SXSW again in 2007. After that we started working together on things.

We were both in New York at the end of 2008 so we were hanging out. Ti was finishing the sound mix on House of the Devil and I was starting the film that eventually became Silver Bullets. It was very organic for Ti to get involved. When he was not working on House of the Devil, he was hanging out with me, so I started to put him in the film. It was a small role at first and over the years of shooting it became a much bigger role. Ti introduced me to Larry early on and Larry jumped right in as well. Larry and Jane Adams lived across the street from each other, but they had never met. They had even been in some films together, but they shot at different times. So we would all meet up every day and shoot whatever ideas I had.

Eventually Ti finished work on House of the Devil and went back to Los Angeles. I went back to Chicago where I live. The film became more difficult to shoot and it took me another 2 years to finally finish it.

AEC: What is your relationship to horror cinema in general? The reason I ask is, I think, quite apparent: you’ve recently cultivated a really interesting creative relationship with Adam Wingard, working more and more within the genre film circuit. Can you talk about how you guys met and about your collaborative process in general, outside of the genre films as well?

I’m reaching a point as a filmmaker where I want my films to be an experience for the audience. Early on, I was happy to put things on screen that I thought were interesting, and that was enough for me. I was rebelling against everything I learned in film school (plot, character, composition, etc.) I’m slowly embracing cinema again, and horror films are a way back in for me. I like that they’re escapist and easily allegorical.

I think Adam Wingard is a brilliant filmmaker. He’s one of the most talented people working right now. He and I work in a very similar way, so even though our films are quite different it’s really easy for us to collaborate. We met at the Sidewalk Film Festival in Birmingham, Alabama in 2008. Then I ran into him again there in 2009 and soon afterwards he asked me to act in a segment of his film What Fun We Were Having. I had a great time working with him on it and he cast me in A Horrible Way to Die a few months later.

That year, in addition to his two films, we worked together on [Bernard & Eric Shumanski’s] Blackmail Boys [2010] (he was DP and I acted in the film), Art History, Autoerotic and Caitlin Plays Herself. It was a very fruitful collaboration that produced a great deal of work in a short time. Since then, I’ve acted in You’re Next and he was my DP on Marriage Material [2012]. I also cast him as an actor in a film I shot in October called 24 Exposures. .

For the people who know Adam’s films, I think it’s funny that he has worked on so many small relationship films with me.

AEC: I don’t believe in pigeonholing at all, but let me ask this for the sake of discussion: considering you’ve been known mostly for relationship/romantic dramas, how do you relate you recent work in horror films? Is it about exploring new territories?

I believe the only way to get better at something is to practice. Making a horror film is no different from making a relationship drama in that regard. Being on a film set is a learning experience and I’m grateful that Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett (who writes Adam’s films) continue to invite me to be part of their projects.

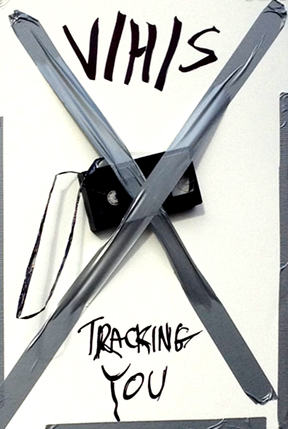

It was through Adam and Simon’s lobbying that I was able to direct a segment of the horror film V/H/S, which just premiered at Sundance and will be released by Magnolia Films in the U.S. and Canada this year. Simon wrote the segment and Adam was my DP, so I was able to learn from them and try something new.

It was through Adam and Simon’s lobbying that I was able to direct a segment of the horror film V/H/S, which just premiered at Sundance and will be released by Magnolia Films in the U.S. and Canada this year. Simon wrote the segment and Adam was my DP, so I was able to learn from them and try something new.

AEC: Friends and press have jokingly called Wingard’s films “mumblegore” film. I’m sure you get this all the time, but has “mumblecore” ever meant anything to you – as a mode, or movement? Do you relate to this grouping of American independent cinema?

I certainly relate to a lot of the films and filmmakers who are grouped into the Mumblecore label. I’m friends with and I have worked with Andrew Bujalski, Aaron Katz, Frank V. Ross, the Duplass Bros., Lena Dunham and Lynn Shelton, so there’s a lot of overlap and collaboration there. But it has always felt like a community to me, not a movement.

The label has been helpful in the sense that it has given journalists something to write about when the films don’t have movie stars in them. Now that making a film isn’t the struggle it used to be, the hardest part is getting anyone to see the work when it’s finished. Mumblecore has been useful in that regard, so I feel lucky to be associated with the word.

AEC: Do you think that – perhaps increasingly now that you, Wingard or Ti West are actively collaborating on each other’s projects – it constitutes a discernible “scene” in American independent filmmaking?

JS: The “scene” has existed for a long time now, but it’s becoming clearer lately how wide ranging it is. My group of friends and collaborators encompasses horror filmmakers, documentary filmmakers, theater performers, musicians, etc. When Mumblecore first started showing up as a word, and people were writing things about the films, I think there was an assumption that it was a very small, insular group of people interested in the exact same thing. I think it would be hard to look at my body of work today and assume that.

I’m sure there are a lot of people who hate my films and love Ti’s films, or vice versa, and the same goes for Adam, but as people realize that we’re all friends and collaborators, the picture gets more complicated. We’re muddying the water and making it harder to distinguish between art films and genre pictures, which is exciting. It feels a bit like the Roger Corman heyday, when he had a lot of future Oscar winners making cheap exploitation films.

I don’t have an image I’m trying to propagate or protect. I just want to work with talented people. Ti West, Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett are some of the most talented people I know. Doing the V/H/S horror film also introduced me to David Bruckner, Glenn McQuaid and Radio Silence, who are all amazingly talented as well. I think a lot of great filmmakers come out of horror. It’s a good genre to experiment and learn in. The expectations are low, which is always a nice place to be coming from as an artist.

When I look at the way journalists and critics talk about David Gordon Green now, I get so annoyed. He started out with a very artistic film, which brought him to the attention of the “serious” critics, and now there’s a palpable sense of disappointment from his early champions regarding his new work. It’s such nonsense. The guy is a filmmaker and he’ll hopefully make 20 or 30 more films and some will be comedies and some will be dramas and some will probably be horror films and who knows what else, but the people who like his early films should be applauding him for being true to himself. It’s rare to see a filmmaker cover such a wide swath of genres and subject matter. Most people end up copying themselves because they’re afraid to change or try something that might not work.

It’s hard to change or expand as a filmmaker unless it’s in the direction of tasteless to tasteful. Nobody wants to see you move the other way. So horror filmmakers are in a good position, because they can always get more tasteful.

AEC: Denomination aside, your aesthetic alone has changed immensely in a few years, not only as you develop skill as a filmmaker but also as technology changes the medium. What is your relationship to technology and to which extent do you let it influence or inform your work? I’ve observed that your films are very much grounded in the present rather than in nostalgia for the past, cinematic or otherwise. Even in a film like V/H/S, having Skype as the horrific device seems like a bold move, if only because it is slightly ahead in time than video. Is nostalgia a part of your work? I shooting on film something you’d consider?

JS: I try and let my films reflect what I see around me. As people have gravitated toward laptops, cells phones, small portable cameras, etc., I have tried to include these in my films. I like the idea of my films serving as a time capsule of how we used technology at specific points.

I’m happy that you think my films are grounded in the present. I think so too. I am not a nostalgic person, and when I find myself getting nostalgic, it’s easy to remind myself why it’s important to live in the present. Regarding film, I think it’s absolutely possible to shoot on film without being nostalgic, and I will probably try that soon.

AEC: While we’re speaking of technologies, I think it’s inevitable to get into the question of distribution. Was making Marriage Material available for free on Vimeo for a limited time, or the subscription system you’re currently working on with Factory25 for 4 of your 2011 films, a response to the current means of distribution of your films?

JS: I’ve had a good relationship with IFC and they’ve made my films available to a large audience around the world, but it’s not realistic for them to release 7 of my films in a year, so I’ve been playing around and exploring new ways to get my work out.

I have a large audience outside of America, so that is a big consideration for me when I’m thinking about distribution. I want to make the new work available to everyone. I also want to think about the films and what’s right for each film. Marriage Material made sense to put on Vimeo, but I wouldn’t have done that with Art History. Each film needs its own considerations.

I’m open to any new technology and any new way to distribute a film. There are exciting developments each day and I would always like to be at the forefront of these changes.

AEC: And the classic closing line: what’s next for you? You’re a stunningly busy guy and we want to know! Any collaborations we should know about?

JS: I’m finishing up a new film, 24 Exposures, which is an erotic thriller of sorts, modeled after late-night cable films from the early 90s. And I’m also finishing up a drama called All the Light in the Sky, that I’m making with Jane Adams. We worked on the story together and she stars in the film. Larry Fessenden and Ti West are both in this film as well, but it has no horror elements. And I’m still working with Factory 25 on the Joe Swanberg: Collected Films 2011 set. We’re making a lot of cool stuff to send out with the films.

—–

SILVER BULLETS trailer:

JOE SWANBERG COLLECTED 2011 FILMS trailer:

March 1, 2012

March 1, 2012  No Comments

No Comments