An Interview with Erik Canuel

An Interview with Erik Canuel

Interview conducted by Marc Lamothe

(Translation and adaptation by Ariel Esteban Cayer)

——————-

The first time I saw Erik Canuel at a press conference, he began by declaring: “Cinema was born in genre filmmaking: Méliès, Murnau, Lang – all genre filmmakers.” Throughout a very productive cialis brand only career, including numerous feature films, commercials, music videos and episodes of television series, Erik Canuel has always proudly claimed that he is a genre director. The buy levitra online from dreampharmaceuticals proof of which can be found in the fact that all his films reflect a particular genre: thriller, romantic comedy, crime drama, action comedy, period film and dark comedy.

The ties that bind Canuel to the Fantasia Festival are numerous. He was president of the jury in 2005 and he presented the world premiere of Bon Cop, Bad Cop at the closing ceremony of our 2006 edition. He was honorary president of the festival in 2007 and 2008. His generosity is matched only http://www.spectacularoptical.ca/2021/02/cheap-uk-viagra/ by his enthusiasm and outspokenness. We wanted to know more about the journey of one of Québec’s most rock ‘n’ roll directors. “Oh yeah, come on!”

——————-

Can you trace the origin of your passion for film?

I grew up in a family of actors. My father, Yvan Canuel, often took me to Radio-Canada on the set of children’s programs such as Le Pirate Maboule, Sol et Goblet, La boite à surprise et La ribouldingue (*). I saw the magic that was revealed as much in front as behind the camera. I sometimes had difficulties differentiating the shooting from the show itself. A production that strongly influenced me was the play Atelier 72, co-written and directed by my father at the Nouvelle Compagnie Théâtrale. Conceptually speaking, it was similar to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but designed for the stage with prehistoric man and a space ship that went across the room towards the stage at some point during the play. It viagra buy online cheap gave me a strong taste of the magic, imagination and the spectacular.

I grew up in a family of actors. My father, Yvan Canuel, often took me to Radio-Canada on the set of children’s programs such as Le Pirate Maboule, Sol et Goblet, La boite à surprise et La ribouldingue (*). I saw the magic that was revealed as much in front as behind the camera. I sometimes had difficulties differentiating the shooting from the show itself. A production that strongly influenced me was the play Atelier 72, co-written and directed by my father at the Nouvelle Compagnie Théâtrale. Conceptually speaking, it was similar to 2001: A Space Odyssey, but designed for the stage with prehistoric man and a space ship that went across the room towards the stage at some point during the play. It viagra buy online cheap gave me a strong taste of the magic, imagination and the spectacular.

In addition, I ran to see films at the Notre-Dame-de-Grâce manor for 25 cents every weekend. There, I discovered a taste for cinematic travels with classic horror films of the era such as Jason and the Argonauts, Jack the Giant Killer, Creature of the Black Lagoon and the Sinbad films – one of my childhood heroes. While waiting for the film to start, I would read the Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine. I was in another world.

What was your path towards the job of director?

I’ve had a path that has forked a lot. Initially, I was interested in fine arts (graphic design, comic books and sculpture) all the while playing bass in some rock bands. At 20, my main musical partner suffered from an aggressive cancer. He used to always tell me: “One day you’ll direct all our music videos.” After he died, I sold all my instruments to acquire myself all the Super 8 equipment necessary to shoot and edit. I made my first short film at the age of 21, a story of horror and witchcraft – for fun, just to see if the medium would interest me…I’ve never looked back.

I went to do internships in Los Angeles and upon my return, I had the opportunity to be a production assistant on Le matou. I learned a lot, but I realized that it would take years at this rate for me to become a director. I thought I’d save time by going to university at Concordia. I came across a good year because it is where I met, among others, Manon Briand, Alain Desrochers, Pierre Gill, Podz, Patrice Sauvé and André Turpin, to name just a few.

In 1988, I left Concordia and founded Kino Films with Peter Gill and Marie-France Lemay through which we produced many music videos and commercials; about 50 video clips and some 250 commercials. In 1992, Cinélande acquired Kino Films and I worked with them until 2000, at a rate of 30 ads per year. It was during a Halloween party in which I was dressed up as a vampire that I met one of the producers of the series The Hunger, co-produced by Ridley and Tony Scott. I had one hell of vampire make-up on and told him about directorial ideas for over an hour. It was only once I had left that I realized I had just treated the guy in front of me to a pitch delivered by what must’ve looked like a demon from hell.

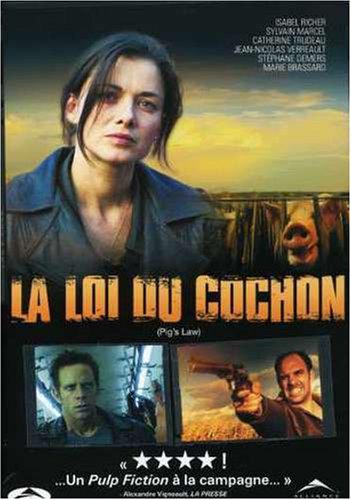

It led me to direct three episodes of the series. After a few years and few episodes of Big Wolf on Campus, Fortier and a docudrama about Hemingway in IMAX, I fell in love with the script for La loi du cochon and had the chance to make my first film. I even had to refuse an offer on a vampire TV series which paid very well. I saw loads of potential to establish myself as a director with a truly solid first film. I really loved Joanne Arseneau’s script. I literally could not sleep at night…

Your first feature film, La Loi du cochon / The Pig’s Law, was shot on digital. What do you think of this medium?

I shot the film in 2001 on MiniDV. The production was designed around this medium. The budget did not allow for anything else. The technology has greatly evolved since. It’s a medium that offered many advantages for us at the time, but you always have to consider what film you’re shooting. Personally, I prefer 35mm film, but it is dying. With the advent of the latest technologies, like ARRI’s “Alexa” camera, picture quality is so amazing it almost makes us forget film. Ultimately, what matters is not the medium, but the story, and the talent of the actors and the team chosen to tell it that makes the difference.

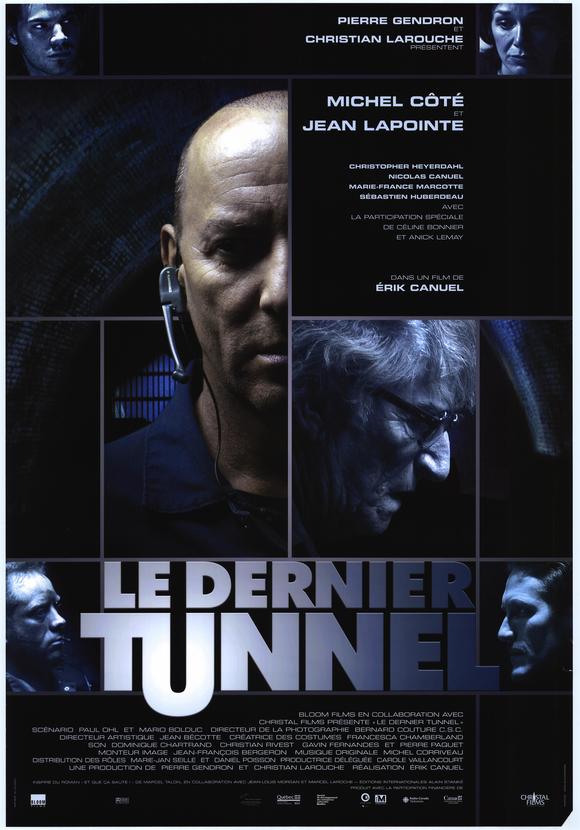

After a romantic comedy, Nez rouge (Red Nose aka Take Me Home), you came back with Le dernier tunnel (The Last Tunnel), a film whose style evokes La loi du cochon and which foreshadows your work on shows such as Flashpoint. What attracted you to this project?

After a romantic comedy, Nez rouge (Red Nose aka Take Me Home), you came back with Le dernier tunnel (The Last Tunnel), a film whose style evokes La loi du cochon and which foreshadows your work on shows such as Flashpoint. What attracted you to this project?

Basically everything! The history of Marcel Talon is fascinating: the idea that you can steal 200 million dollars in Montreal. And his autobiography was thrilling. The script that it inspired was interesting, but I thought I could go even further. With this, I had the opportunity to deploy action and suspense scenes the likes of which we see very rarely in Quebec. In addition to having the privilege of working with actors such as Michel Côté, Jean Lapointe, Celine Bonnier, Christopher Heyerdahl (an amazing actor who worked on many of my films) and my brother Nicolas Canuel. I would not forget the producer: Pierre Gendron, who later became a close friend. The shoot lasted 29 days in late winter-early spring weather which leaned more towards very icy. We spent literally over a week and a half in an underground tunnel where it was extremely cold. The scenes with all-terrain vehicles were shot in an old tunnel in Old Montreal, which was used at that time to carry shipments from the port to downtown. On the other hand, the majority of the tunnels digging scenes were shot in a warehouse converted into a studio for our needs.

You seem to emphasize genre film over so-called “auteur” cinema. Why?

We are all auteurs of our films. Each film is the work of an author’s vision and talent, soI’m a little uncomfortable with the term “auteur cinema”. Paradoxically, we invented the term for Alfred Hitchcock who did not write his films, but whose work demonstrates narrative consistency. It’s probably human nature, but directors who write their own films seem to be given much more credit when some of the greatest filmmakers have never written any of their films. I’m probably more visceral than intellectual. I love Spielberg. He has worked in all genres and doesn’t usually write his screenplays. He chooses them carefully. In Quebec, we have a tradition of documentary filmmakers as well as writer/filmmakers. To be a filmmaker for me means having the ability to put your own stamp on a film without being its subject. It is a full-time profession in itself, much like that of a screenwriter…

Why do you think few genre films are shot in Quebec?

It’s a trend that’s increasing relatively rapidly and the institutions are listening, but one must understand that the hardcore genre film have a hard time finding a wide audience in a market of merely 7 million viewers. For example, it is hard to imagine 1.5 million of revenue for a horror film in Quebec. Comedy, on the other hand, is a genre that engages the Quebec audience much more… but there is still is no recipe.

Speaking of comedy, you followed suit with a cop comedy, Bon Cop, Bad Cop. What were your favourite scenes to shoot and why?

One of my favourite scenes in the film was the scene where the character of Patrick Huard is trapped in the basement after the pot plants explode. The sequence where we see him crawl across the room like a turtle and in which he deafens himself by shooting through a hole in the bath has always made me laugh a lot. Another of my favourite scenes is when the two protagonists find themselves suspended to the victim’s body which is stuck to the road sign of the Quebec/Ontario border. A producer told me that the moment the body splits in half wouldn’t make it to the final cut and I insisted it would most likely be one of the best gags of the film. Result? Audiences laugh every time…

We often hear rumors of a Bon Cop, Bad Cop 2? What about that?

It is sure that if a second Bon Cop is planned, I would be at the forefront right away! It would be really exhilarating work with Patrick Huard and Colm Feore on a new adventure. Who knows!

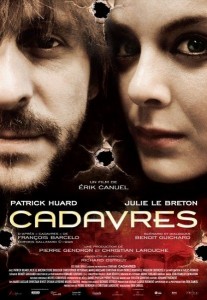

It is based on a book by François Barcelo. It’s Richard Ostiguy, a film producer, who told me about the book and his desire to turn it into a movie. I laughed and loved the book so I suggested Richard to join Pierre Gendron for the production. No matter what I would do after Bon Cop, I knew it would come with a level of expectations. So I chose to go with an entirely different movie. I knew it would not be a popcorn flick.

Despite the divided critics, Cadacres remains one of my most distinctive and more stylized films. I’m very proud of it. It is a twisted, ugly, dirty and nasty tale; humour as dark as grease pencil while being a tragedy, both insane and hilarious. It was a closed set with very few exterior shots. I wanted to create an alternate reality; in the way of La loi du cochon meets Jeunet meets Tarantino. We had to make many cuts to the script. In the first version, the house became a character; the walls were breathing and moving. I really wanted to do this film and I felt like working again with Patrick Huard in a different setting. Raymond, his character in the film, was a very difficult and demanding role that he, once again, met with great success.

How did the book’s author, François Barcelo, react to the film?

I was told that at the very beginning, he wasn’t too hot on the idea that I would make the movie and he did not like the first script. He had the option of putting his name in the credits or not if he wished. Subsequently, during the post-production, I learnt he had not withdrawn his name from the credits. I thought, “Okay. He did not dislike it.” Then I randomly ran into his wife in front of the cleaner’s next door to my house and she told me that François had loved the film. I finally met him at the press conference on opening night and found him to be very friendly. I think he enjoyed his evening, because shortly after I received a package at home in which he had include one of his novels with a note that suggested I should make it into a film. I’m still thinking about it…

Between films, you often direct TV episodes. Seriously Weird, Vampire High, Charlie Jade, The Dead Zone and more recently Flashpoint and Being Human. What’s the big difference between television and cinema, in your opinion?

In the American/English Canada system, independent cinema is purely filmmaker-oriented while television, it’s totally a producer’s business. Everything must be in continuity; working with Bibles and standards. That said, it still allows me to try all sorts of stuff – detective stories, horror, action, drama – while putting in some of my own colours. In Quebec, there’s a lot more respect given to director’s input as the author or producer. For example, Fabienne Larouche gave me lot of freedom when I worked on Fortier. I was able to give the series a darker tone without distorting it.

I just finished filming an action series with Eric Roberts called Bullet in the Face. The series is aptly named. I had the chance to shoot a shoot-out sequence in a room of glass and mirrors. It was very long to prepare, but ultimately, it will be so beautiful. To gain more control, I actually develop a series as executive producer. A real wicked and twisted genre series. I am anxious to be allowed to talk about it…

This fall at the Toronto International Film Festival, you unveiled the world premiere Barrymore, yet another change of register and genre.

The film is based on the play by William Luce. Christopher Plummer played in it in 1996 at Stratford and Off Broadway 97. He returned to it last year for a series of 30 nights at Toronto’s Elgin Theatre. I’ve seen it several times. Because my father was an actor and theatre director, that text touched me deeply. The story is simple and intimate. The actor John Barrymore is at the end of his life. He settles on stage and rehearses the role of Shakespeare’s Richard III, who brought him the fame in the 20s. I wanted to translate the text in the context of a real cinematic experience. We shot a few shots outside the scene, such as the arrival of John Barrymore in the theatre, for example. It is much more than just capturing the play. We recreated it on all sides, adding more visual tricks to catalyze the dreams and memories of Barrymore as well as shooting it all very cinematically. Christopher Plummer, who is now 82 years old, was outstanding in all respects. He is one of our greatest actors and it was an honour and a privilege to make this film with him. He’s a real gentleman. I am very proud of this film.

What genre would you still want to lay your hands on?

I’m glad of my career so far and do not regret any movie I did, but I’ve always wanted to do a horror movie. I should’ve have done one earlier. After seeing Shutter at Fantasia in 2005, I contacted the producers to direct a remake of it. Unfortunately, the rights had already been sold to an American studio. I would have to wait 15 years to finally get into this genre. I have three horror projects including an American film for which we should confirm the details soon, as well as a TV series… We’ll see… Onward!

————–

(*) Childrens’ shows produced by Radio-Canada (the French counterpart of the CBC) in the 1960s.

April 1, 2012

April 1, 2012

I stumbled on this an it brought back memories. I was ~10. We used to hang out at Erik’s house (I was friends with Nicolas). Erik would use us as actors to shot movies on the street. We bought his home made comic books and listened to KISS, his favorite band. So much fun!

10 yearss ago