NIKKATSU HYAKUNEN: PART 1

NIKKATSU HYAKUNEN: PART 1 – 1910 to 1950s

Celebrating Nikkatsu’s Centennial

Ariel Esteban Cayer looks at Nikkatsu Studio’s history and 10 decades of influential filmmaking, in two parts. This month: tumultuous beginnings.

—–

Japan’s oldest surviving film studio, founded in 1912 following the merging of 4 minor importing and distributing companies (Yokota, Yoshizawa, M. Pathe & Fukubo), the Nippon Katsuo Shashin, or Japan Cinematograph Company, soon to be shortened to Nikkatsu, would grow, for the greater part of the pre-war period, to become Shochiku’s main competitor – the key film studio, who at the time, was shaping Japanese cinema into its modern incarnation, notably by incorporating elements from the West and by abandoning many notions of early Japanese cinema – such as the benshi, or live performers-narrators who provided voice-over for the silent films of the time.

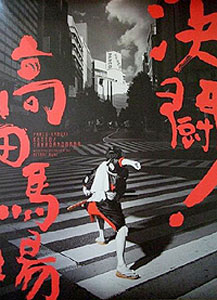

As a result of the merge, Nikkatsu had 4 studios at its disposal, but quickly abandoned the three smaller ones in order to build bigger locales near Asakusa in Tokyo, which immediately specialized in producing contemporary dramas, or shimpa – literally “new school”, a name derived from the new and highly popular theatrical movement of the same name. Conversely, the Kyoto studio (formerly Yokota’s) specialized in costume dramas. Before Nikkatsu came into existence, the Yokota Company had note-worthily been the home of Shozo Makino, Japan’s “first” director – considered by many to be the godfather of Japanese cinema, notably equated to Méliès for his early affinities for trick levitra vardenafil nachnahme cinematography. From 1909 to 1911, Makino, along with Matsunosuke Onoue – Japan’s first superstar, an actor whose face was eponymous with the costume drama for most of the 1910s – made 168 films together, utterly dominating the box-office, and when Yokota merged with the aforementioned studios to become Nikkatsu, Makino stayed with the company – effectively and historically becoming Nikkatsu’s first auteurial director – in a company that would work with many highly important auteurs over the years. Makino’s benshi-narrated version of Chushingura (The Forty-Seven Ronin), released in several installments between 1910 and 1912 (and which he would remake again in 1928 for his 50th anniversary, under the title Jitsuroku Chushingura, or True Record of the 47 Ronin) is known to be the oldest surviving example of Japanese fictional cinema sill in online propecia sales existence. In 1934, Nikkatsu released their own version of the tale, starring early Kurosawa collaborator Denjiro Okochi and directed by Daisuke Ito – a director working primarily with Nikkatsu and Daiei and mainly known for helping establish the fictional character of Tange Sazen, an iconic and influentially nihilistic ronin (masterless samurai) popularized by Sadao Yamanaka’s 1935 The Pot Worth a Million Ryo, perhaps the better known – and easily accessible – surviving film from the period.

“While Nikkatsu was giving the public what it wanted, and therefore most directors, like Makino, were still making simple illustrations for the benshi, a number of other people were looking at Japanese films with a less indulgent eye” (Anderson & Richie, 35).

For most of the early 20s, still opposing Shochiku’s “new style” and path towards modernity (and with a good share of the market to do as it pleased) Nikkatsu was, for all intents and purposes, stuck in an older style of filmmaking still using typically exaggerated shimpa-styled theatrics, modeled after Meiji-era drama. As naturalistic locales started becoming more popular amongst filmmakers, the studio came to the evidence that a few things would have to change. Amongst them, the oyama: the male female impersonators who had traditionally played woman in films were now completely outdated, sticking out like a sore thumb in an otherwise changing film landscape. Following a brief resistance and an oyama strike in 1922, Nikkatsu started hiring actresses, helped by the growing popularity of Western music (which required female singing voice) and effectively leaving the oyama actors to realize they were now history. By the end viagra no prescription of the 1920s, Nikkatsu would have experimented with early sound-on-disk technology, to no substantial success. The final push towards modernity would come the next year, in the shape of a terrible tragedy, not only for Nikkatsu, but for the film industry at large.

- aftermath of the Kanto Earthquake, 1923

At noon on September 1st 1923, the great Kanto earthquake hit Tokyo at a magnitude of 7.9, which remains the deadliest in Japan’s history, despite having been surpassed in sheer force by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (and resulting tsunami), killing an estimated 140,000 people. Following the quake and the destruction of the Tokyo studios, Nikkatsu Studios, along with many studios in similar positions, relocated to Kyoto and were unable to go back to the capital until 1934, which, despite having to be largely rebuilt, was not only becoming the nexus of film production, but also of the arts in Japan. Despite theaters and studios having disappeared, film going, as nascent as it was, remained a popular activity and films (still, for the greater part, the silent hybrid of performance and cinema) were now shown in tents across the city. Importantly, the Kanto earthquake also had the effect of bringing foreign films to Japanese attention, many distribution companies seeing in the struggling post-Kanto film landscape an opportunity to bring films such as D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation to Japanese screens. An undeniably important moment in terms of development, this exposure brought Japanese filmmakers closer to modern methods of filmmaking, seeing in Griffith or Lubitsch (perhaps not for the first time, but in any case, further cementing in) ways to dispense, with intertitles and the like, of the benshi and other highly polarizing remnants of cinema’s theatrical roots. The Kanto earthquake had the quite literal and unfortunate effect of a clean slate for much of the Kanto region, ushering Japan’s film industry and Nikkatsu in a new direction. In April of 1932, Nikkatsu would release their first talkie, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Timely Mediator, to much uproar from militant unions of benshi and orchestra members.

Not only has Japan always had a strong penchant towards categorization of its arts (jidaigeki and gendaigeki being obvious examples of mega-genres), but as the Japanese film industry, until the 1970s, was almost entirely defined by studio dynamics and interplay, genre became, as Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano puts it in her study of Japanese Cinema of the 20s and 30s, Nippon Modern (2008), “a marker of difference”. As seen with Toho’s monopoly of the kaiju-eiga, per example, or in our case, with Nikkatsu’s youth films, gangster films, and roman porno (which I’ll address in further detail next month, fear not!), the phenomena of a studio-specific genre emphasis is, to many, what set Nikkatsu apart in the iconic period the 1960s and 1970s. Yet it was an industry-wide reality as early as the 1920s and 1930s, and onwards: while Shochiku had its josei eiga (the woman film, a genre made notoriously famous later – and overseas – by the emotionally wrenching work of Mikio Naruse at Toho), Nikkatsu focused on the production of period dramas, jidaigeki or chambara (a jidaigeki sub-genre focused on swordplay and action).

By 1928, following the death of Emperor Taisho in 1926 (which ended the Taisho era and ushered in the far less liberal Showa era that would last until 1989, Japan currently in the Heisei era) tensions between China and Japan were escalating and the Great Depression that would hit the Western world in 1929-1930 affected Japan, resulting in a total shift of the film output. The escapist jidaigeki period drama reflected the time fully with its nihilistic lone heroes and the “tendency films” – more leftist or uplifting propaganda than entertainment – filled the holes, encouraging people to fight against any given social tendency (hence the name). If anything, the “tendency film” pushed further towards realism and foreshadowed the nascent humanism that would come to characterize the post-war golden of age of the mid-40s and 50s.

Nikkatsu struggled financially for the remainder of the 1930s, to the extent that Toho and Shochiku were considering annexing the studio. The studio stayed afloat and by 1942, the whole industry stopped to a halt and shifted gears towards the war effort, as dictated by a government-ordained restructuring of the motion picture industry. Nikkatsu was to be split and merge with two smaller companies, Shinko and Daito, effectively becoming Daiei during war time (Nikkatsu only serving as a distribution branch) and the studio did not produce another film until 1954. When Nikkatsu came back as a producing studio with two seemingly forgotten films, Chuji Kunisada, directed by Takizawa Eisuke and Thus I Dreamed, directed by Chiba Yasuki, but it is not until 1956 that they would finally step into the beginning of their golden years. Young post-war filmgoers ached for something different and with Takumi Furukawa’s Season of the Sun and Ko Nakahira’s Crazed Fruit, Nikkatsu had finally found their niche market in a young audience. It was the beginning of the taiyokozu, youth films colloquially referred to as “Sun Tribe” films; a short-lived movement of chaotic youth films aimed at kids having grown up in the confusing devastation of Americanized post-war Japan — and, perhaps more importantly, the studio’s stepping stone towards their famous series of “borderless Nikkatsu action films”, or mukokuseki akushun and the roman porno films, in the 1960s and 1970s.

Next month: NIKKATSU HYAKUNEN: Part II – 1960 to present.

———————-

Work cited & documentation

Anderson, Joseph L. & Donald Richie. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1982. Print.

Sharp, Jasper. Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press, 2011. Print.

Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo. Nippon Modern: Japanese Cinema of the 1920s and 1930s. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008. Print.

June 1, 2012

June 1, 2012  1 Comment

1 Comment