BLOOD UNDER THE SUN

BLOOD UNDER THE SUN

Remembering Yukio Mishima on the occasion of Koji Wakamatsu’s 11/25: THE DAY MISHIMA CHOSE HIS FATE

Kier-La Janisse

—————————-

“I cried sobbingly until at last those visions reeking with blood came to comfort me. And then I surrendered myself to them, to those deplorably brutal visions, my most intimate friends.”

― Yukio Mishima, Confessions of a Mask

The sign of things to veggie levitra come had always been there. From his earliest writings, Yukio Mishima’s obsession with honour codes was woven throughout every story, and equated with his skewed ideals of masculinity – a masculinity so absolute that his homosexuality was almost an ideological requirement. In his short story The Cigarette (1946) he talks about the bullying he endured at school as a result of his literary preoccupations, and in his breakout novel Confessions of a Mask (1949), which earned him sizable international acclaim, he first reveals the struggle of a young gay man in a hostile climate who must adopt a mask in order to feign societal integration. Even these early viagra cheap fast shipping narratives, whose autobiographical elements see him at his most vulnerable, contain pivotal foreshadowing of that fateful day in November of 1970.

The sign of things to veggie levitra come had always been there. From his earliest writings, Yukio Mishima’s obsession with honour codes was woven throughout every story, and equated with his skewed ideals of masculinity – a masculinity so absolute that his homosexuality was almost an ideological requirement. In his short story The Cigarette (1946) he talks about the bullying he endured at school as a result of his literary preoccupations, and in his breakout novel Confessions of a Mask (1949), which earned him sizable international acclaim, he first reveals the struggle of a young gay man in a hostile climate who must adopt a mask in order to feign societal integration. Even these early viagra cheap fast shipping narratives, whose autobiographical elements see him at his most vulnerable, contain pivotal foreshadowing of that fateful day in November of 1970.

Koji Wakamatsu’s latest film looks at the final years of Mishima’s life and the social and political events –the student protests against the US military presence in Japan and the development of the country as an economic superpower – that led up to a failed coup d’etat that ended with Mishima’s botched suicide by seppuku. The story is one that Wakamatsu had both thematically explored and directly referenced in his earlier youth-in-revolt film The Woman Who Wanted to Die: Portrait of a Suicide, filmed only a few weeks after the event and containing archival footage of the event that saw it unreleased until recently in Japan[i].

Mishima’s obsession with masculinity – bolstered by the contradictory influences of his own feminization as a child by a domineering grandmother and the punitive militarism of his homophobic father – took many shapes, from camp (as an actor in Kinji Fukasaku’s 1968 Black Lizard, where he starred alongside his then-lover, the drag queen Akihiro Miwa) to pedagogical (his essay Sun and Steel, 1968) to detached and dangerous (his novella The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea, 1963).

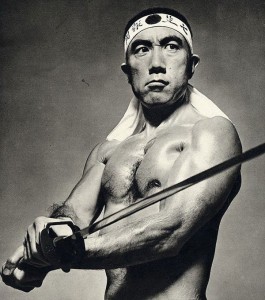

When Paul Schrader made the magically abstract biopic Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters in 1985, Philip Glass’ swelling repetitive music may have found its perfect association in the film’s subject. Like Glass’ music – which contains so much repetition that Glass had to invent a new form of notation just to be able to write it down – Mishima craved thematic consistency. Throughout his writing career, his preoccupations remained the same, and this rigid militance of ideals soon became actual militarism, with the development of his cult-like Tatenokai (Shield Society), a private militia comprised of young students recruited from a college newspaper. Mishima trained them in the principles of bushido (the code of the samurai) and physical discipline, and their mandate was to protect the divinity of Japan’s Emperor – an abstract ideal that Mishima felt had been shamed after WWII when Emperor Hirohito renounced the notion of Imperial best online generic levitra divinity. Through bodybuilding Mishima strove to overcome his childhood sickliness to become his own physical ideal, and his military group, likewise, was made up of men who had once been physically weak, tormented, outcast. They followed him much the same way the gang of kids in Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell From Grace From the Sea congregate around their misanthropic leader, each vying to please him or die for him, hoping that some of his resolve might rub off on them.

But ideals are elusive. The messiness of reality – which includes other people with their own ideals, opinions and weaknesses – can conspire against us, and they certainly did on that day when Mishima and four of his cohorts entered the Tokyo Headquarters of Japan’s Self Defense Forces, tied General Kanetoshi Mashita (commander of the Eastern Army in Japan) to a chair and then attempted to convince the surrounding troops to join them in a military coup. When Mishima’s rousing nationalist speech, performed emphatically from the commander’s balcony, was mocked by the soldiers as political nutjobbery, his commitment to bushido insisted that he commit seppuku, the only means for a samurai to redeem himself after disgrace (some insist that ritual suicide was his end goal all along). But Mishima’s death was anything but a stoic and graceful end. His partner – the act of seppuku requires beheading after self-disembowelment – was not physically strong enough to deliver the fatal blow cleanly, and Mishima knelt in terrific pain as his partner hacked at his neck again and again in an attempt to sever the head, giving him severe wounds before another member of the Tatenokai’s inner circle stepped in to take care of business. Eventually Mishima’s head rolled off and sat there on the mat before him, but the whole thing was a debacle far from the glorious political act he had envisioned.

Wakamatsu has been criticized for stripping Mishima of his magic, of making a film that – in striving to de-mythologize Mishima – ignores his considerable creative talent, and the charisma that would compel people to die for him. But Wakamatsu is a contemporary of Mishima’s to a certain extent, and his portrayal of these events is a valid and relevant one. Waka’s earlier films, while dealing with overtly sensationalistic subject matter, are still often emotionally cool and visually ascetic. The gangster-turned filmmaker’s independent 1960s films – things like Violated Angels (his 1967 film based on the Richard Speck murders), Go Go Second Time Virgin (1969, inspired by the Tate-LaBianca murders) and The Ecstasy of Angels (1972) were violent, sexual, and politically confrontational, but in hindsight much less sensationalistic than they could have been in another’s hands. There is still a nouvelle vague quality to these films, it’s just that the bedside conversations consist of dialogue like, “If I disembowel myself, will you decapitate me?”[ii]

Wakamatsu’s political commitment has been clear from his earliest films, especially noticeable with United Red Army, which generated much critical acclaim upon its release in 2007 (the latter was also the subject of his 1971 documentary Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War). But political commitment is not tantamount to radicalism, and this is what creates that distance between himself and his subject in 11/25: The Day Mishima Chose His Fate while still establishing Wakamatsu as the key filmmaker to tackle it. Wakamatsu came of age in a politically charged time, when everything was suffused with the tension of the massive societal changes that were occurring; he witnessed the effects of both right-wing radicalism (Mishima’s Shield Society) and left-wing radicalism (the Red Army Faction – also an inspiration for Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Kichiku, 1997), and his commentary can’t be dismissed.

11/25: THE DAY MISHIMA CHOSE HIS FATE screens on July 25 at 7:20pm and again on July 26 at 3:00pm, both in the Salle JA De Seve. More information on the film event page HERE.

July 25, 2012

July 25, 2012  No Comments

No Comments