GENRE GERONTOLOGY: Old Age in Cult Cinema

GENRE GERONTOLOGY

The Horrors of Aging, from ABUELITOS to WRINKLES

Kier-La Janisse

——————-

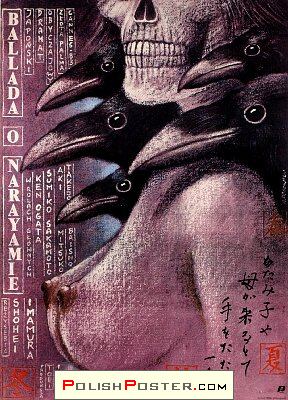

I once asked my stepfather cialis100mg what he wanted to happen to him when he became old and senile. “Just put me on a train headed west and forget about me,” he said. It buy viagra seemed absurd at the time, but honestly how different is this from what really happens? The concept of aging is explored in any number of films, from straight drama to exaggerated allegory, but the one thing all these films have in common is the sense of otherness bestowed upon the elderly as ‘a problem to be dealt with’. In Shohei Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama (1983), the tradition of a small village is to carry one’s elders to a mountaintop and abandon them there, where they die one after the other in a makeshift mass grave. The abandonment has both a pragmatic and a symbolic purpose; there is an attempt to preserve the memory of a living person, and to let them die privately, with dignity. Even cheap discount levitra a dog will crawl under the house to die. But genre films are often less subtle: old people become demons, witches and zombies bent on sucking out the life force of the young. Through the lens of the horror film, they become something to fear.

Our fear of old people is almost as primal as our fear of the dark. In genre films like Black Sabbath (1963), The Haunting of Julia (1977), Suspiria (1977), The Sentinel (1977), Next of Kin (1984), Abuelitos (1999 – and featured on Fantasia’s Small Gauge Trauma DVD), Drag Me to Hell (2009), Livid (2011) and so many more, the aged and infirm are threatening and monstrous. This fear is obviously predicated on their closeness to death, but this taxonomy doesn’t hold when held up to the 19th century cult of invalidism, where illness was fetishized to the point of causing an abundance of hypochondriacs. While the 19th century ‘invalids’ eventually referred to people of all ages (usually women) who suffered from frequent ill health (real or imagined), this trend was initially fueled by the attention bestowed upon young women dying of tuberculosis. People would flock to be near them, hoping to catch some sign of divinity by being in the vicinity of someone canadain cialis straddling the portal between life and death.

The difference here is the age of the infirmed: the TB angels were typically young and their frailness and skeletal glow were looked at as celestial qualities. They would be enthusiastically tended to, and splayed out on daybeds to buying generic cialis mexico rx receive visitors. The aged, by contrast, are shut up in dark rooms, attics or un-traversed wings of large houses. Or in less gothic terms, dumped in nursing homes where they can drool, shit the bed and be forgotten about.

Why are we afraid to look at the old? And how does horror as a genre seize upon this feeling, to turn awkwardness into abject dread and terror? Much of this has to do with tried-and-true concept of The Uncanny. An old person is more uncanny than a young person, because they were once something that they are no longer; they are both ‘familiar’ and ‘other’ at the same time; the very recipe for the uncanny. Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) – and the ‘Grand Dame Guinol’ films that proliferated in its wake – offers up a great use of the uncanny. In Aldrich’s film (itself owing a debt to Sunset Boulevard) the grotesquerie of the aging Baby Jane Hudson (Bette Davis) is emphasized by the preserved ‘cuteness’ of the Baby Jane doll that sits by observing her maniacal tirades.[i]

The elderly cross over into otherness when the memory starts to go, they lose hearing or eyesight, (horror films especially mythologize the blind), when mobility is stunted, speech slurred. In Keith Wright’s Harold’s Going Stiff (2011), the degeneration of a person into old age is likened to a zombie virus. Harold (Stan Rowe) goes to the doctor complaining of ‘stiffness and lack of mobility’ and subsequently cases like this – which are increasing exponentially – are diagnosed under the name ‘Onset Rigors Disease’. Victims of Rigors Disease initially stop talking and emoting (and strangely it’s all men who suffer from it) while stage 2 of the illness is marked by the deterioration of mental faculties, and stage 3 is a ‘dangerous zombified’ state in which they suffer from forgetfulness, disorientation and finally violent outbursts. At which point they are hunted down and killed by rather overzealous homeguard-type vigilantes.

Harold is the first to be diagnosed with the illness, but his degeneration is much slower than the other cases. As such, he is able to communicate what is happening to him – making him the human face of a dehumanizing virus. Unfortunately this also makes him a target of study for curious, exploitive scientists. The zombies who are not killed are put into homes where they are herded and treated like insane children. With his nurse-turned-best-friend Penny (Sarah Spencer) Harold visits one of these homes and recognizes his own future in the vacuous, violent zombies. He too will be restrained and spoon-fed one day. “I wish I could just go to sleep and never wake up,” he says listlessly. Harold is incredibly sympathetic – lonely, afraid and increasingly helpless – and there is nothing more heartbreaking than Penny being forced to abandon him to his fate.

This concept of aging as a form of zombie invasion is also explored in Yann Chayia’s Les Petits Hommes Vieux (2005, the English title is the inaccurate translation ‘Men From Older Space’). In Chayia’s film, old people are zombified creatures that only become aggressive when they are systematically ignored by the young. But their passive existence – content to sit on a sofa in silence, perhaps accruing the decor of the elderly like afghans, needlepoint throw pillows and cat pictures – causes great anxiety to the ‘living’ who run from them at every occasion. But eventually the young must realize that they too, will become one of the ‘undead’ before they know it.

As a point of comparison, in a non-genre film like Randall (Grease) Kleiser’s autobiographical, National Registry inductee Peege (1973) – starring Bruce Davison of Willard and harrowing afterschool special The Wave – the character of Peege is equally ‘other’. Once a vital, cackling, permissive grandmother, now a blind, senile shell of a person, no one knows what to do with her or how to talk to her. The film is a 25-minute exercise in awkwardness as each family member struggles to relate to her as anything other than an objectified obligation. They still call her by her nickname, which recalls a time when she would share cookies and illicit late night Creature Features with her doting then-teenaged grandson (Davison). Now a university student who lives far away, he is shocked at her degeneration and watches in anguish as his family steeps in guilt and condescension. They only visit once a year; it’s easier to just look away and leave her to be tended to by the paid help. But before he leaves, her grandson leans over and says “Your laugh would always make me happy,” hoping to connect, and the final shot indicates that Peege understands, but is unable to respond. Peege is not a genre film[ii], but a student thesis film that became a mainstay of educational programming in schools. Its horror lies in the utter helplessness of both parties.

Often this feeling of helplessness is reconfigured as resentment (which is more emotionally manageable) and can swell to such proportions that the caretakers turn on their charges with overt acts of violence. In Mark Jackson’s Without (2011), a troubled teenage girl (Joslyn Jensen, in a brave performance) mysteriously takes up a job as a temporary live-in caretaker for a catatonic man in an isolated rural home, and is driven to extremes as she starts to imagine that he is actually mobile and moving things around in the house while she is asleep. Her suspicion mounts, reinforced by emotional problems she came to the job with, and she becomes verbally and physically abusive to her client. Similarly, in Robert Morin’s disturbing Petit Pow! Pow! Noel (2005) a man (Morin) shows up at the care facility where his tyrannical father has been hospitalized for 20 years after being paralyzed in a car accident. Armed with a video camera that captures the defenceless man’s every humiliation, the son aims to psychologically torture the old man, to confront him with past crimes against his family before carrying out his execution. But this sadistic treatment is somehow preferable to watching the old man get bathed, changed and fed, unable to do anything about this shocking loss of dignity.

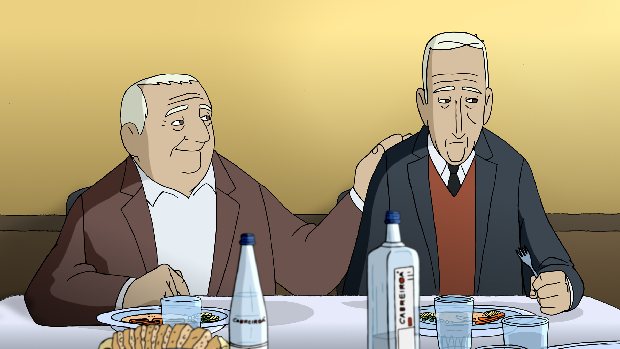

This is where a film like Ignacio Ferreras’ Goya award-winning Wrinkles (aka Arrugas, adapted from the graphic novel by Paco Rosa) is a welcome genre addition: a charming 2D animated film about the friendships that develop between a colorful crew of geriatrics placed by their families at a nursing home. Wrinkles veers clear of grotesquerie, but inevitably the onset of dementia is depressing subject matter, and the film keeps a fair balance between levity and the sometimes grim realities of its context. Overall, the film is a celebration of the potential of the twilight years. The families who cannot communicate (either out of pity, awkwardness or lack of interest) see only a person in decline – a perception that shifts when we see the residents of the nursing home forming a tight knit crew whose feistiness flies in the face of the mind-numbing conformity around them. They watch as the other residents line up for an hour just to go to bed, and are determined that they won’t end up the same way. They take advantage of their perceived senility by pulling pranks, breaking rules, and getting into trouble; hijinx that recall those of a very leisurely-paced summer camp movie. But the care facility’s top floor, that reserved for the hopeless cases – those with dementia and advanced physical deterioration – looms over them all like a dark shadow.

From a genre perspective, Wrinkles is probably closest to Cocoon (minus the aliens), but that only points out the rarity of any dignified depiction of old age on genre screens. Wrinkles doesn’t hold its characters’ aging against them; it posits the elderly as something other than incontinent, spitting, comatose things whose usefulness has run out. Sure, sometimes genre films use the aged as a vehicle for humor (Stuart Gordon’s Stuck [2007] for instance) – and there are always wily grandparents like Barnard Hughes in The Lost Boys (1987) or Bette Davis in Burnt Offerings (1976) who still have all their faculties – but more often the elderly are monsters, like the cannibalistic men in Paco Plaza’s short film Abuelitos (1999) or the gnarled cadaver of Mario Bava’s ‘A Drop of Water’ segment of Black Sabbath (1963) who haunts her thieving caretaker after the latter steals a valuable ring from the old woman’s fresh corpse.

A Drop of Water was an obvious reference point for Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury’s sophomore feature Livid (2011), the setup of which takes a cue from Bava’s creepiest film; a young home-care trainee (Chloé Coulloud) is taken on the usual rounds by her new employer, administering daily shots and meds to a series of neglected senior citizens. The elder nurse (Catherine Jacob) is not physically unlike Jacqueline Pierreux in A Drop of Water, and is equally uncaring and dismissive of her clients. Their travels lead them to a sprawling decrepit hillside estate – the kind with its own cemetery out back and local superstitious rumors that keep the neighbourhood kids far away – and of course our young protagonist is immediately intrigued. Told to wait in the car for this one, she disobeys, far too curious to see the bowels of this verboten domicile. This gives production designer Marc Thiébault a chance to show off his colours, as the house really is impressive in its cluttered decor, complete with ceiling-high dusty bookshelves and taxidermied animals. The latter play a role not only in the developing plot(s) but also symbolically, referring to the film’s preoccupation with preservational practices; just as the animals are preserved in a hardened, uncanny form, so the old people in the film are preserved – their lives prolonged with medicines and machines.

The matriarch of this particular house – once a famous dance instructor named Deborah Jessel – is the perfect vision of geriatric horror: comatose, attached to a respirator, stiff and cadaverous, her long fingernails unkempt and threatening like claws, lying in the center of a massive carved oak bedframe flanked by books, mirrors, and other antiquities. Around her neck hangs an oddly-shaped key that keeps the house’s dark secret locked away undisturbed. But the young trainee, wooed by the older nurse’s stories about an alleged ‘treasure’ hidden in the house, resolves to break in later that night with her boyfriend to try to locate the treasure – a momentous error, to be sure.

While the plot takes many twists and turns, what is interesting here is how effective as a horror image a person is just by virtue of being old. The heavy breathing pulse of her respirator combined with her background as a ballet instructor immediately calls to mind Suspiria’s shadowy directress Helena Marcos, whose hair is equally frizzed, her face crumpled and cracked with age, her lips thin and lizard-like. Jonathan Martin’s An Evening with my Comatose Mother (2011) is a campy rendition of this same imagery, which remains the genre film’s contribution to gerontology. As in most genre films, reality is exaggerated as a means of being confrontational. Horror in particular loves to hit those targets, and while picking on old people might seem like shooting fish in a barrel, the connection between the fears about aging that horror exploits and the fractured way we relate to the elderly in real life is palpable enough to warrant examination. But in the meantime, if horror films have anything to say about it, we’re not going to get over our fear of aging anytime soon…

[i] Although brief, Tom Geens’ short film Shame (2006) features great moments of age-envy, tyranny and the physical and emotional manipulation of a woman with a possibly dysmorphic ailment. See the film online here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2OPgsO_QxK8

[ii] Peege’s only genre connection other than the casting of Bruce Davison is that it was produced by David Knapp, who was simultaneously producing Steven Spielberg’s Something Evil for CBS.

July 30, 2012

July 30, 2012  No Comments

No Comments