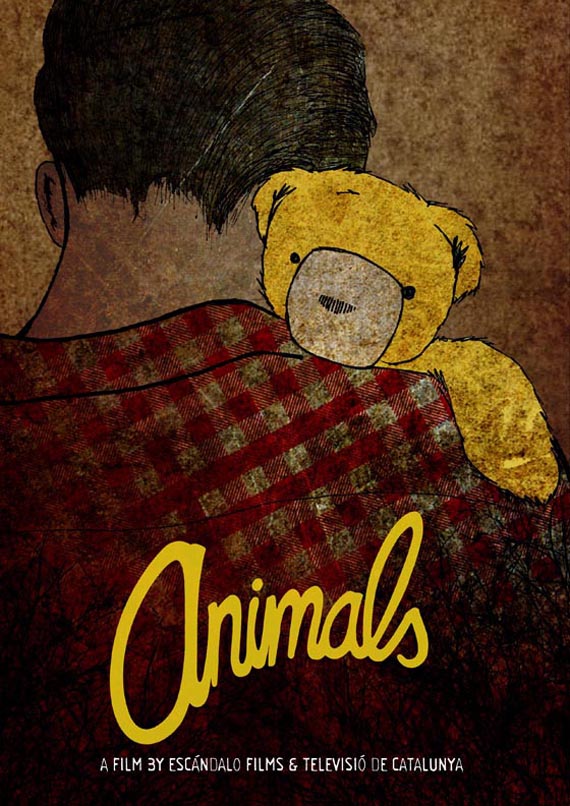

GHOST STORIES OF YOUTH: “ANIMALS” (2012)

Spanish Director Marçal Forés Answers Some Weighty Questions About His Disturbing, Cerebral Teen Horror-Drama, ANIMALS [Fantasia 2013]

[Note: This article discusses some narrative details that may be considered spoilers.]

***

Spanish filmmaker Marçal Forés’s stunning debut feature Animals (2012), screening twice this year at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival (see the film’s schedule HERE), is a cerebral and often troubling meditation on alienated youth struggling against the horrific paradigm shift into adulthood. The film has been compared to Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko (2001), and it features scenes that match that film’s occasional slippage into the more nightmarish aspects of teen reality. Yet, where Kelly’s storytelling pivots largely around his film’s unique time-travel concept, the dreamlike narrative of Animals is decidedly more experimental, often propelled by the associative logic of daydreams that renders the reality of the film as a near-totalizing projection of the psyche of its protagonist, Pol (played by Oriol Pla). The better comparison for Animals may be to poetic films about haunted youth that resonate with a touch of the fantastic-uncanny, such as Sophia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999), Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003), or—going further back—Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962) and Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975).

Animals revolves around a teenaged boy, Pol, whose closest friend and confidant is Deerhoof, a childhood stuffed bear that speaks to him in synthesized, robotic English. Whether Deerhoof’s presence in Pol’s world is a supernatural secret, or a pathological manifestation of Pol’s troubled interior world, the delicate relationship between the two is deeply-felt and, ultimately, tinged with tragedy. Pol struggles to detach himself from the seeming protection of youthful innocence, represented here by Deerhoof. Pol prefers an isolated world tinctured by fantasy to the inevitable struggles awaiting him on the other side of the threshold to adulthood. Pol’s conflicts extend to his sexual identity, as well. He resists the romantic attentions of girl-pal, Laia (Roser Tapias), finding himself drawn to an aloof outsider, Ikari (Augustus Prew), who seems to haunt the same liminal space between fantasy and reality as Pol. Ikari struggles to feel something visceral in this life by cutting himself, a practice Pol reluctantly and clumsily adopts after his first sexual encounter with Ikari. Forés presents this encounter through a sort of awkward lyricism, as the two characters lean into each other across a footpath, attempting to bridge the distance between their bodies and emotions in a kiss—a moment that ends abruptly with Ikari slashing Pol’s arm with the knife he uses to cut himself. The scene is both erotic and shocking, as Ikari represents the lure of sexual desire mingled with the emotional and physical pain that Pol associates with crossing over into adulthood.

Forés’s 2010 short film Friends Forever offers some insight into the director’s interest in exploring alienated youth. Both Friends Forever and Animals feature protagonists who have difficulty separating a “safer” fantasy world from the more traumatizing reality of the present. In the earlier film, another teenager, George (Sean Hart), ultimately cannot come to terms with the harsh and lonely reality left to him in the wake of the death of his intimate friend, Chris (Sean Bourke). George resists this reality of loss ultimately by turning to suicide so that he might haunt the world in a perpetual past that sees both youths suspended forever on the cusp of deepening intimacy.

Friends Forever’s ambiguous merging of the supernatural and psychological as a way of mapping the passage of youth into adulthood is territory that Forés treads in Animals, as well. Both films represent perpetual innocence as a sort of ghostly existence that Pol and George are reluctant—even terrified—to leave. In Friends Forever, George’s ultimate suicide is, perhaps controversially, a way to maintain the degree of unfettered childhood intimacy that he has lost with Chris, and that all adults may seek to recapture from youth. In Animals, Deerhoof, Pol’s talking stuffed bear, represents this element; here, the character is attached to his childhood itself, or at least its sense of protection from the problems of the adult world. When Pol, in a heartbreaking scene, ties the bear to a rock and throws him into the reservoir that acts as the film’s unconscious, the death of the bear is the death of youth, and Pol’s eventual return to the bear is his refusal to accept the final “mutation” into adulthood that he has been resisting all along. In a moment that suggests his own suicide, Pol dives from a bridge, descending into the murky waters to cut Deerhoof loose with the very knife that Ikari (a name associated in Japanese with both anger and anchor) used to shock him into a sense of the visceral bodily pain of adulthood.

Both Animals and Friends Forever were shot by visionary cinematographer, Eduard Grau (a film school pal of Forés’s), who at 27 shot Tom Ford’s A Single Man (2009), and has since gone on to shoot the incredible Buried (Rodrigo Cortés, 2010), which takes place almost entirely inside a coffin, as well as the video for Lady Gaga’s “Born this Way” (Nick Knight, 2011), and The Awakening (Nick Murphy, 2011), a conventional ghost story enlivened by Grau’s rich, painterly textures. Grau’s fluent juxtaposition of vast and intimate spaces brings a tone of cerebral contemplation to the films he lenses. In Animals, this sensibility comes through as Pol’s friend Laia pounds on a huge pane of glass separating her from warning Pol, who wanders distractedly in the foreground of the shot, of potential danger at school. In Friends Forever, a similar disorienting moment occurs as two teens discuss George in whispers, as he wanders the school grounds much farther off in the distance while suited, masked groundskeepers spray chemicals on the school’s pristinely manicured shrubs and foliage.

Both films end with an ambivalence and openness that is refreshing in that they are as oddly optimistic as they are devastating and melancholy. It may be controversial to suggest that Pol’s and George’s wholesale resistance to reality is in any way hopeful, yet in these films such retreats to fantasy serve less as indications of these youths’ inability to withstand the burning entry into adulthood than as a rejection of the idea that experience must come at the price of a loss of innocence. Disturbing as the films’ final scenes may be, they find the dead walking in tandem in a permanent fantasy world of their own making, or reunited in the kind of intimacy that comes with childhood play.

It is not surprising that both Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, the mainstream film industry’s two standard voices on cinematic salability, have expressed reservations about Forés’s film’s potential for distribution and success at reaching wide audiences. These publications’ reservations about Animals are the very things that make it remarkable: its tendency to speak directly and knowingly to a cult audience (as if this were a bad thing), its deliberately dreamlike narrative and pacing, and its self-conscious poetry.

Below, Marçal Forés responds to some questions about Animals.

***

Spectacular Optical: What inspired you to make ANIMALS? Are their any films or filmmakers that you would cite as an influence on your work?

Marçal Forés: The original inspiration was a short that I did as a school exercise back in 2005. I was studying at the NFTS [The National Film and Television School] in the UK back then. The short (also called “Animals”) was basically a project that we had to shoot with no time and hardly any crew, so I played the main role in it while talking to a toy teddy bear I bought in a shop. The idea for the short basically came from a mixture of an interview I saw from a musician called Dennis Driscoll in which he was interviewing himself with some questions that he was throwing from his computer’s text reader (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=epIsx106S_8). Also there’s a music video from Pavement of their song “Stereo” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnrM4UjaQmY) that has one squirrel lip synching Stephen Malkmus that gave me idea of making a toy talk. I fell in love with the idea of being partners with a toy as if it were a real human being.

SpecOp: ANIMALS taps into a tradition of other visionary films that evoke the world of youth as melancholy, dreamlike, haunting and uncanny, such as Peter Weir’s PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK, Sophia Coppola’s THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, Richard Kelly’s DONNIE DARKO and Gus Van Sant’s ELEPHANT. Were these films in any way a direct influence in ANIMALS?

MF: Absolutely. We are talking about films that I personally felt thrown into when I watched them. Some of them are personal favorites. I do think that adolescence is a very dramatic veering into adulthood. It marks the end of freedom and the beginning of reasoning as a way of life.

SpecOp: Your earlier short film, FRIENDS FOREVER (2010) shares similarities with ANIMALS’ poetic exploration of alienated youth. Both films, for example, feature protagonists who have difficulty separating a “safer” fantasy world from the more traumatizing reality of the present. Would you call FRIENDS FOREVER a sort of prototype for ANIMALS?

MF: Could be. It was after seeing Friends Forever that the producer of the movie thought of me to start writing the feature that would turn out to be Animals. However, I think I’m personally attracted to the possibilities that film gives to blur fantasy and reality. I do enjoy when the border between these two worlds is completely erased. Then is when the “poetry” comes, as you call it. In my case it is pure excitement.

SpecOp: Has your vision of youth changed between making FRIENDS FOREVER and ANIMALS?

MF: I think this vision has gone darker in Animals. I’ve got the feeling that the more I grow up the less sense it all makes. I guess both films goes along with this idea. I don’t know. Maybe it’s the audience who should be answering this question.

SpecOp: Both ANIMALS and FRIENDS FOREVER are very sophisticated in their treatment of sexual identity—especially youthful desire, and the struggle of young people to feel emotionally connected to the people around them. Do you find that bringing the supernatural into your films makes these difficult topics easier to handle, or helps you to convey them more effectively?

MF: It definitively helps the characters gain more sense of what’s around them. And also some perspective on what’s in front of them. I think, in a way, that imagination or fantasy, help these characters find their grip with reality.

SpecOp: Charles Burns’ graphic novel BLACK HOLE, which you reference in ANIMALS, describes a world of adolescents struggling with random, disturbing bodily mutations. FRIENDS FOREVER also references mutation in the form of orchids that some of the youths in the film seem to use as a drug. Can you explain your interest in this idea of the traumas of youth as a form of mutation?

MF: Hmm … Maybe to make look someone “mutant” is a way to portray what for the adult world/masses is weird or feels like it’s out of the loop. I do remember being quite depressed when I read Black Hole years ago. For some reason the comics seemed to hit me on my weak points at the time I read them. And it was not until years later that I started writing the film that I realized the connections between the comics and my script. The pain and guilt of Pol’s journey after losing his soul mate Deerhoof were similar to the painful discovery of this underworld to which the teenagers of Black Hole realized they belonged.

I must say, though, that despite the apparent darkness of the mutation, this anomaly is like the forbidden fruit. Like pure feeling. Freedom of thought.

SpecOp: Would you call ANIMALS a horror film? A ghost story? A fantasy film? A dream (or nightmare) film? All or none of the above?

MF: I dunno. You choose the one you like the most!

SpecOp: Your cinematographer, Eduard Grau, has a talent for “painterly” films that emphasize surface, light, color and texture, and that experiment with expansive or closed spaces. Grau shot both ANIMALS and FRIENDS FOREVER, and his style seems perfectly matched with the dreamlike quality of your films. Can you comment on your collaboration?

MR: Edu and I have been good friends for years. We actually studied together both at ESCAC (Escola Superior de Cinema I Audiovisuals de Catalunya) in Barcelona and later at the NFTS in London, so to partner up with him always felt the natural thing to do. During the shoot the crew was making jokes about us all the time. Many said we were like a mean couple arguing all the time. It’s true, when we work we hate each other!

However, I do think Edu has a great eye for beauty, and he definitively was the person to trust in both projects.

***

When I asked him about future projects, Fores commented, “It’s taking a while to wash ANIMALS off my skin. I have started mumbling about some projects that are not yet developed. I hope they’ll soon turn into something, but this is an early stage.”

In the meantime, Forés notes that he recently has finished editing an older short entitled Paradise, which offers hints of the evocative use of space apparent in Animals and Friends Forever. He has also made two music videos for a production company called Canadá. One of these, for a song by a popular Spanish glam/synth-pop band called Fangoria, entitled “Desfachatez” (or “Impudence” https://vimeo.com/70101849), abounds with playful horror imagery. The second, for a song by Spanish “friki” (describing a kind of retro-geek 50s aesthetic) pop band Papa Topo, entitled “Meteoritos en Hawaii” (https://vimeo.com/62168744), shows further evidence of Forés’ professed love of comics and Manga.

July 24, 2013

July 24, 2013  No Comments

No Comments