THE SNUFF OF LEGEND

13 Questions for Simon Laperrière, Co-author of the New Book, Snuff Films: Naissance d’une légende urbaine, with a discussion of the 1982 Mondo-Style Doc, The Killing of America

A testament to the diversity of the offerings at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival is its blend of programming for both genre fans and (horror of horrors!) genre scholars. Along with the lectures by Daniel Bird on Polish poster art and the Polish fantastic, and opportunities to query outré filmmakers such as Andrej Zulawski, the 2013 Fantasia recently hosted a discussion of snuff films by Fantasia programmer Simon Laperrière and Antonio Dominguez Leiva, Professor in the Département d’études littéraires at L’Université du Québec à Montréal, as part of the launch of their book, Snuff Films: Naissance d’une légende urbaine (June 2013, Editions du Murmure).

Accompanying the launch was a screening of The Killing of America, a 1982 documentary co-written by Leonard best online generic levitra Schrader (brother of filmmaker Paul Schrader). It generic cialis online canada is a riveting film, both subversive and exploitative in its traumatic refiguring of twentieth-century American history via a series of shocking images. As Simon Laperrière implies in his description of the film for the Fantasia website, The Killing of America is a snuff film; or rather, it is a compendium of the only kind of films that can come close to being called “snuff,” those which capture actual deaths, usually accidentally. The term “snuff” is a bit of a paradox, since technically the term implies footage of real death “meant for commercial purposes” (as Laperrière defines it in the interview below), but legally, no such film could ever be distributed or shown commercially. The Killing of America is clearly meant to raise questions about the degree to which Americans have been forced to resort to violence to be heard, yet its slow-motion lingering and replaying of Great tool. Normalizes erection very well. Canada cialis levitra: there are a lot of legitimate mail-order pharmacies in this country. its fascinating imagery is discomfiting. Whether or not The Killing of America crosses an implicitly understood moral line in this respect is a question that lies at the heart of the distribution of all footage that chronicles actual deaths, no matter what context one gives for the replaying of it. Regardless of these issues, The Killing of America paints a very different picture of the American Dream in the twentieth century, and through its traumatic imagery forces uncomfortable, but critical questions about American policy at home and abroad.

One of the earliest images of death recorded on motion picture film in the U.S. is Thomas A. Edison’s 1903 film, “Electrocuting an Elephant,” a publicity film of the electrocution of Topsy, an elephant who helped to build Luna Park at Coney Island. (Watch it—again and again—here.) Edison used the footage as a tool to promote the effectiveness of his DC (direct current), now in use, as opposed to Nicholai Tesla’s AC (alternating current) process. So, Topsy’s filmed death was essentially an infomercial. This kind of exploitation of death (even of an animal) has become taboo in current media ethics, and yet curiosity around the topic of real cialis100mg death remains.

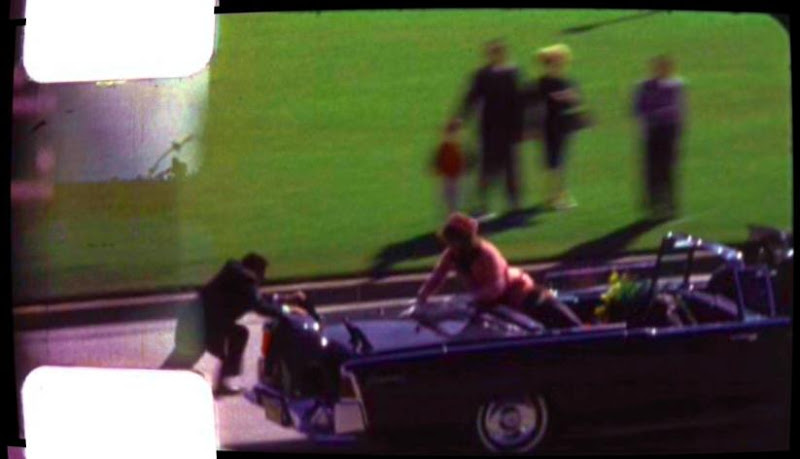

The issue of public distribution of snuff films has currency in today’s headlines with the recent arrest in Edmonton, AB, of Mark Marek of bestgore.com on charges of “moral corruption” for distributing footage of Luca Magnotta’s butchering of Concordia student, Lin Jun, under the title, “1 Lunatic 1 Ice Pick.” The crux of the case against Marek seems to turn on his keeping the footage available on his website, even after he knew it was real, and not a hoax. It is difficult to say what distinguishes the degree to which Marek is morally reprehensible regarding his distribution of these images—perhaps because of the degree of brutality and suffering they depict, or due to their contemporaneity with the murder itself, or that his website is devoted to depictions of such imagery for entertainment purposes. The viewing public is more than willing to scrutinize certain other films showing death and violence, perhaps because they are less extreme in their content, or perhaps offer a degree of historical distance and visual blur that leave something to the imagination, as one finds with history’s most famous ‘snuff’ film, the Zapruder film. Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm home movie footage accidentally capturing the assassination of John F. Kennedy on 23 November, 1963, is perhaps history’s most famous filmed murder. Shown in stills in Life magazine until it was finally aired for the first time in 1975, the Zapruder film is now freely available on YouTube (Watch it below), and is likely the most scrutinized piece of documentary footage in cinema history.

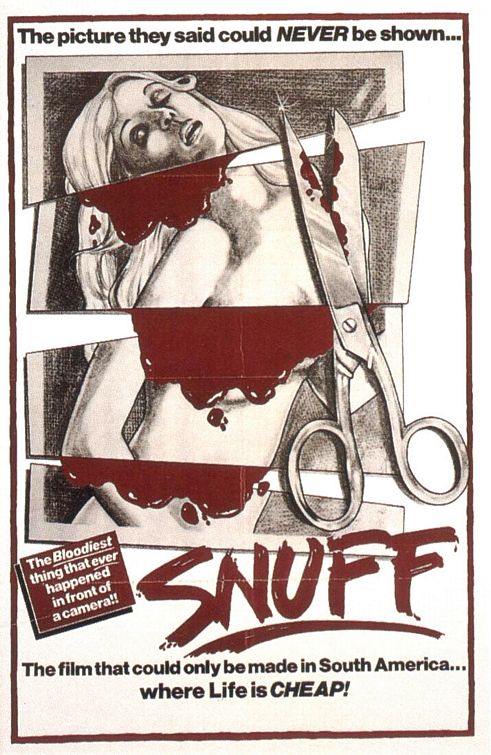

Films such as Alejandro Amenabar’s Tesis (Spain, 1996) and Scott Derrickson’s recent Sinister (US, 2012), along with independent, found-footage fare such as the unreleased The Poughkeepsie Tapes (US, 2007) and Evil Things (Canada, 2009) have attempted to tap into the mystifying nature of the snuff film. Most intriguing about the snuff imagery in these films is its use by sinister folk or forces to manipulate others based upon their fascination with images of death. The issue of death imagery as a hoax is an element that has been courted by films such as Mondo Cane (Italy, 1962), Snuff (US, 1976), Faces of Death (US, 1979) and its sequels, the August Underground trilogy (US, 2001, 2003, 2007), and proto-found-footage films such as Cannibal Holocaust (Italy, 1980). These films encourage audience speculation about the veracity or “reality status” of much of what they are seeing. Their audiences come prepared to test their ability to source out the line between what is real and what is clever fakery. Because the truest snuff film is the record of a real human death, moral implications arise around the screening and distribution of such materials.

It is with these issues in mind that I recently spoke to co-author Simon Laperrière, who also serves as head programmer for Fantasia’s “Camera Lucida” section of avant garde films.

***

Spectacular Optical: Tell us a little bit about your new book, Snuff Films: Naissance d’une légende urbaine. How did it come about? What inspired it? How did you come to be working together?

Simon Laperrière: The book tells the story of the birth of an urban legend that is still around today. According to it, there’s a secret network somewhere selling to rich individuals reels of films showing actual murders. As of 2013, we have no proof that such snuff films exist. In our little essay, we try to retrace the media climate in which the rumor was born. The book also features what I think is the very first academic analysis of the feature film, Snuff.

The project started as a Master’s thesis I’d been working on for a few years and finished right before Fantasia started. I’ve had the idea of turning it into a book, but thought Antonio should be involved in it’s conception because he has studied snuff films on his own and actually made a few discoveries I was not aware of. We’ve known each other for a few years and have worked together on various occasions, so we knew we could do something together that we could both be proud of. The book is the result of a dialogue between us on the subject of snuff movies as well as the audiovisual objects that have given the myth some credibility over the years.

SpecOp: Has this been a difficult subject to address academically? Would you say that scholars remain largely dismissive of the snuff film, or its audience?

SL: Very few scholars have studied the urban legend since its birth in the 70’s. Most of the literature on the subject are fanzine articles or books written by journalists trying to prove the rumor (a great example is Yaron Svoray’s Gods of Death (1997), a hilarious investigation where the author claims to have seen a snuff film with Robert De Niro!). While such texts can be interesting for their historical and sociological values, they lack the scientific approach we were aiming at. Addressing the subject academically was difficult at the beginning because of the lack of sources. We were pretty much on our own, but this issue actually made project exciting for the exact same reasons. Being amongst the first people in Academia to explore a new field of study is always motivating!

I would agree that scholars are dismissive of the snuff film, but definitely not its potential audience. Many authors have published precious monographs on the reception of violent images. Susan Sontag’s wonderful Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), for example, is a fantastic essay that offers an important reflection that can easily be applied to the hypothetical viewing experience of a snuff film.

SpecOp: What are your thoughts on the public’s scrutiny of such footage, from the Zapruder tape, to the now-iconic “falling man” photograph from 9/11? What lies behind this fascination with images of real death?

SL: André Bazin wrote that cinema is the only medium capable of showing the actual moment of death. I think the fascination behind such images is the ability to see a brief moment in time, but one that possesses a strong symbolic meaning. What we are seeing in the capture of such an intimate moment is actually a reminder of our own fatality. While the Zapruder film is fascinating because it managed to catch on film the death of a star—a president no less!—the photo of the falling man is disturbing because it immortalizes a man facing his own death.

SpecOp: Scholar Joan Hawkins has used the term “paracinema” to refer to films that hover somewhere between exploitation and art film. Would you locate the so-called “snuff film” in this context at all?

SL: Hard to say until we’ve seen an actual snuff film. I think they wouldn’t have much artistic value, just a “straight to the point” mise-en-scène whose main goal is to show an actual murder. According to the urban legend, as well as their representations in narrative cinema, they would look primitive, like the stag movies were before the legalization of pornography in the 60s. Of course, I could be wrong … After all, it is not impossible to imagine a team of experts using the gear from John Ford’s The Searchers in order to secretly shoot a snuff. But would it be considered art? Are we still talking about cinema when we’re thinking about a film showing a real homicide? I don’t have the answers to such questions.

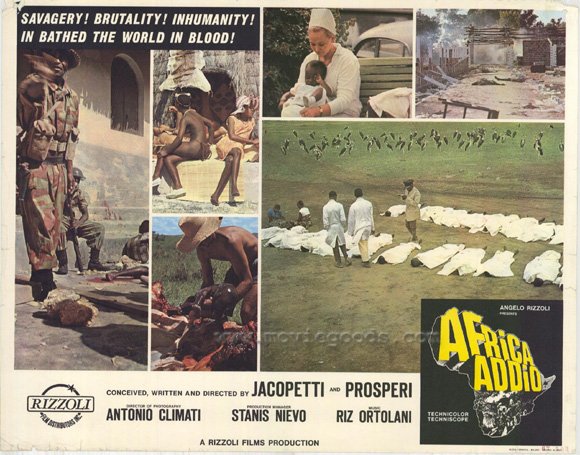

SpecOp: Considering that both types of film involve footage of actual deaths, what differentiates the Mondo film (such as Italy’s Mondo Cane, made by Gualtiero Jacopeti and Franco Prosperi) from the snuff film?

SL: The real deaths shown in Mondos and death films are caught by accident by the cameramen. They didn’t occur for the sake of the film (and yes, I’m aware of the Africa Addio [1966] controversy, but I don’t believe the execution shown was staged by the directors [Jacopeti and Prosperi]). Snuff movies are different because the murder being shown happens specifically for the benefit of the film. [Director Gualtiero Jacopeti was accused of staging the murder of a rebel for the film. Roger Ebert was particularly critical of the film’s tendency towards exploitation of its subjects, and its generally colonialist framing of the end of the colonial era in Africa. Read his review here.]

SpecOp: The term, “snuff,” has been used in a rather foggy way to relate to atrocity footage, both simulated and real—or to a general aesthetic meant to resemble chronicles of death. Some fictional films that are often referred to as “snuff” films—such as Snuff and Cannibal Holocaust—take on this aura because of their convincingly faked death footage, or footage of animal deaths combined with rather convincing faked footage. (So convincing, in fact, that Ruggero Deodato director of Cannibal Holocaust, was arrested and the film seized for a time.) Can you clarify the term, “snuff,” with respect to such films?

SL: They are not snuff films because they do not show real homicides. As authentic as they can look, they are still works of fiction that are inspired by the urban legend. We can call them horror films, found footage movies or even “torture porn,” but they are not snuff films.

SpecOp: In previous interviews, you’ve said that the idea of “snuff films” is essentially an American phenomenon. Could you comment on this idea?

SL: The urban legend was born in the United States during the corrosive time of the 70’s. Violent and obscene images were everywhere because of the Vietnam War as well as the distribution of Mondo and porn films in local theaters. Horror movies were also becoming much more violent and realistic. When you think about it, the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre [1974] looks like a documentary when compared to HG Lewis’ Blood Feast [1963] and 2000 Maniacs [1964]! It was a period of time where the country suddenly appeared more barbaric than ever, an impression that strongly makes credible the rumor of snuff films. To give you an idea, feminist groups were using it as an example of the degradation of women in pornography because such hypotheses seemed real to the public.

Of course, the urban legend did cross the seas over the years. Rumors of snuff films emerged everywhere, in Europe and Asia, especially Japan, but its core is definitely American.

SpecOp: What are your thoughts on Luca Magnotta’s filming of his murder of Lin Jun in Montréal in May, 2012, and the current case against Mark Marek of bestgore.com for “moral corruption” for distributing this snuff footage?

SL: Magnotta’s video appeared online when I was still working on my master thesis. Suddenly, I had the strong impression that a real snuff had been found, a scary idea to say the least! After reading about it, I came to the conclusion that while it’s not technically a snuff film (it doesn’t show the moment of death and was not made for commercial purposes), it is currently the closest thing we’ll ever get to a real one. The existence of such a film is to many a proof of the urban legend because if such video is out there, it becomes impossible not to believe real snuff could be hidden somewhere on the Internet.

Mark Marek’s case is a very complex debate because accusations of moral corruption could potentially open a Pandora’s box. Democracy would let you think that any individual should have the freedom to see anything he wants, but we can understand why the State would put some restrictions on such liberties. Lin Jun’s family has the right to be offended by the online distribution of the Magnotta video; and out of respect for the loss of their son, they also have the right to request it gets taken off the Web.

I’m more worried about the impact of the Court’s decision on artistic freedom. Once the Law can decide what is moral and what is not, it can also start controlling any kind of creation. Hopefully, it is not a sign of the shape of things to come, but considering how conservative our government is in Canada, we should start to be more suspicious.

SpecOp: I tried to access the footage of Luca Magnotta’s murder of Lin Jun as soon as I heard about it. Not right away—I hesitated. But ultimately I went onto bestgore.com to try to catch it before Marek removed the footage. I was unsuccessful … and I felt a combination of relief and disappointment. What’s wrong with me?

SL: The existence of the video was all over the news for an entire year, so it is quite normal that anyone was curious to see it. I think it actually became some kind of challenge test within the online community. People wanted to check if they would dare to see it till the end because they knew it had a graphic content. But such attraction is paradoxical because we want to watch it as much as we don’t. We know viewing it will expose us to real horror, to a face of human cruelty we may not want to be aware of. It also gives us an almost Kafkaesque impression of being an accomplice to the crime, as if, as the viewer, we give the film a reason to exist and somehow become responsible for it. We’re not watching a film out of curiosity anymore, we’re participating in the cult of a crime. A good reason to stay away from it.

SpecOp: Can you comment on your decision to show The Killing of America in conjunction with the launch of your book?

SL: The film is mentioned towards the end of the book, so it made sense to us that we should screen it. It was also the opportunity for Fantasia to show a rare movie that was never distributed in North America, not even on DVD. It’s also a notorious documentary because of its depiction of real violence and is one of the many films that makes the snuff rumor credible.

SpecOp: In your description for the film on the Fantasia website, you call The Killing of America “transgressive.” The film left me in what can only be described as a sort of pleasant quandary about its methods. Could you comment on this?

SL: I felt the film is transgressive in terms of its portrayal of violence. Following the Mondo tradition, it tries to be informative and entertaining at the same time. It never tries to hide the fact the images being shown have a spectacular appeal, but it uses them in order to sensitize us to what they say about the American society. It’s a provocative film that tries to shock as well as educate, not something we see everyday!

SpecOp: Could you give us a list of at least three important snuff-related films, whether anyone actually considers them snuff films?

SL: As bad as it is, we should not dismiss the impact of Michael and Roberta Findlay’s Snuff. It was the first movie that showed an audience what a real snuff film would look like. I’m always impressed by the August Underground trilogy because I strongly believe these movies are the closest experience to the viewing of an actual snuff film. They are so credible that you can doubt, even for just a few seconds, that they could be real. Finally, it’s impossible not to mention Cronenberg’s Videodrome [1983]. It’s a great film, one of my favorites, but also an important movie that allowed the urban legend to adapt itself to new technologies. Here, snuff films are no longer affiliated with cinema, but also with television and VHS. Such a switch from one medium to another allows the rumor to remain actual and appear real to an audience.

SpecOp: Any plans at Fantasia to program a retrospective of films that try to tap into a “snuff” aesthetic?

SL: While not planned, such a retrospective is something that could be quite interesting to do eventually. We could tell the story of the urban legend’s evolution through movies and screen stag movies, Mondos, fictions with an aesthetic similar to what snuff could look like and even TV shows such as CSI and Quebec’s own 19-2. It would take a lot of work to build, but I think it could be quite fascinating to do, be it at Fantasia or elsewhere.

***

Simon Laperrière and Antonio Dominguez Leiva’s new book, Snuff Films: Naissance d’une légende urbaine (June 2013, Editions du Murmure), is available on Amazon.com’s French language site, here. The Killing of America can be viewed on YouTube, below.

August 13, 2013

August 13, 2013  No Comments

No Comments