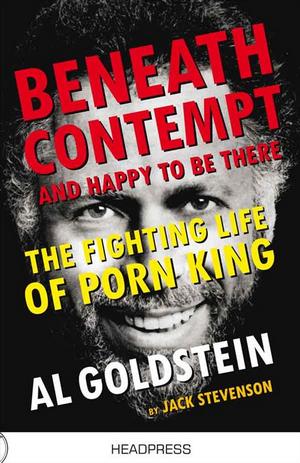

AL GOLDSTEIN: BENEATH CONTEMPT AND HAPPY TO BE THERE

BENEATH CONTEMPT AND HAPPY TO BE THERE

Kier-La Janisse reviews Jack Stevenson’s latest book, about the rise and fall of outré porn king AL GOLDSTEIN

This review was originally posted June 1, 2012. It is re-posted here as a tribute to Goldstein, who passed away today (December 19, 2013).

“It’s a society of many voices, and I don’t want any of them silenced.” – Al Goldstein

————————

Many publishers of taboo, often sex-centric material have been subsequently acknowledged as anti-censorship martyrs – Barney Rossett (Evergreen / Grove Press), “Crazy” Ralph Ginzberg (Eros/Avant Garde), Hugh Hefner (Playboy), Larry Flynt (Hustler), and the subject of Jack Stevenson’s latest tome, Al Goldstein (Screw). And they’d have to be, after all, who was going to protect their commercial interests in court if not them? All became tireless first amendment crusaders by default when their own publications came under attack, but the fact remains that while many others in similar situations surrendered or folded, this tiny faction of so-called smut peddlers soldiered through. And while I’ll always be a Rossett/Hefner girl thanks to early exposure via my dad’s collection of Evergreen and Playboy (no one can deny those classic Playboy interviews are off the hook!), there is something to be said for Al Goldstein’s refusal to moderate anything he wrote with a shred of taste or composure. As Stevenson points out, his role was to be in your face – society’s face, that is – the barbarian at the gate, rushing in to bust open the chastity belts, ready or not.

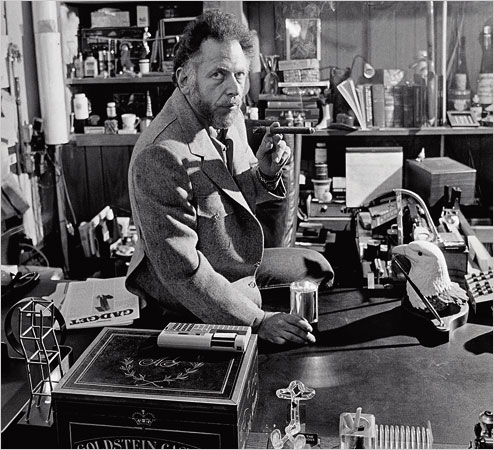

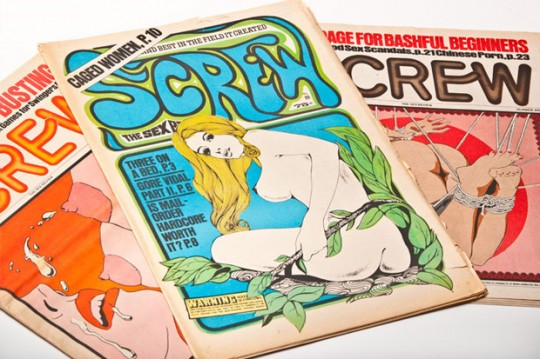

With Screw, Goldstein started an unapologetically rude sex magazine that lasted 34 years and 1800 issues. He rose from being an unknown overweight cab driver to a major voice in the sexual revolution. He hob-nobbed with the rich and famous, and his list of sexual exploits include getting a blowjob from Linda Lovelace and being a sugar-daddy to a young Linnea Quigley. He was acclaimed by the likes of Henry Miller as one of America’s great writers, was a champion of underground cartoonists (who often illustrated Screw’s covers), was sued by Pillsbury for depicting the doughboy and a female companion in compromising situations, produced a film under the Screw banner called It Happened in Hollywood which would be assistant-directed by one Wes Craven, went to federal court multiple times on obscenity charges, became a multi-millionaire and, conversely, a homeless person couch-surfing at a 24-hour Starbucks. And he ain’t done yet.

By Goldstein’s own admission, Screw was for the slobs, the plebes, and basically anyone who couldn’t afford to jet set around the world drinking whiskey and bedding nubile bunny hostesses. “Hef’s glossy parade of perfect air-brushed women symbolized to Goldstein the original fraud; sex as nothing but endless masturbation and one-way fantasy; sex as an activity only the wealthy could afford or were worthy of…Playboy was elitist. Screw was fiercely democratic,” Stevenson writes. (Pg 51) At least this was the line Screw touted. Though he preached ‘sexual honesty’ and explored the act of love with a warts-and-all gusto, the magazine was more humorous than titillating, and remains an interesting countercultural artifact more than a paper aphrodisiac.

Author Stevenson is a noted sex film biographer and 42nd Street aficionado, having penned the books Fleshpot and Land of 1000 Balconies as well as an eye-opening article about Danish bestiality sex star Bodil Jensen for Shock Xpress. He’s also a reputed archivist and curator of vintage smut films, especially those from Scandinavia where he’s made his home for nearly 20 years. Stevenson’s expertise regarding Scandinavia’s sexual liberation history ties in directly with the early years of America’s pre-eminent sex magazines, as pornography was legal in Scandinavia long before it was stateside, and importing Scandinavian films and publications (and then having to defend in them in editorials and, at times, in court) was a major business for exploiteers on the Duece and its vicinity. Both ‘classy’ mags like Evergreen and dirty ‘rags’ like Screw both looked to Scandinavia as an example of how sexual repression in the arts could be lifted without society resorting to anarchy. That’s not to say Goldstein’s mandate wasn’t hedonism all the way – he’s always been a glutton for food as much as sex, and has been famously obese and dangerously diabetic for much of his career – and what made Screw stand out from its contemporaries was its complete lack of political correctness or a need to veil its prurient interests behind a facade of redeeming social value. “A hard-on has its own redeeming value,” he said in a 1974 Playboy interview. The press loved him for these kinds of flip statements – where Hef could seem stiff and disinterested, Goldstein was eminently excitable and quotable. (Unfortunately for Goldstein, so was Larry Flynt, and the book goes to great pains to show how Flynt consistently stole Goldstein’s thunder in the ongoing First Amendment battle). But despite Goldstein’s frequent dismissal of the Screw audience as “unable to read”, the magazine was the locus of enough critical left-wing socio-political discussion to dispute Goldstein’s claims that it was just a working-class ‘fuck’ magazine. He was never able to see how capable he was of flexing his intellectual muscle for his own benefit, instead insisting that the base instincts should be catered to above all else.

It seems that Stevenson was able to sidestep that obstacle that has been the burden of Goldstein’s other print and screen biographers, namely, the participation of Goldstein himself, and “the disruptive mental chaos that follows him around like a cloud.” (pg 208) When former Screw staffer Josh Alan Friedman’s book I, Goldstein: My Screwed Life (co-written with Goldstein) came out in 2006, Steven Heller (a founding Screw art director) reviewed it kindly for the New York Times, but lamented that it lacked in insight concerning the wider scope of Goldstein’s legacy. That seemed to be a starting point for Stevenson here. There was enough material out there from Goldstein’s own mouth, now what he needed was someone with knowledge, but a bit of distance. The book is surprisingly dense considering its compact 208 pages, with Stevenson’s approach examining the effect Screw had on pop culture, on social mores, on the sexual revolution, and follows the magazine’s trajectory as Goldstein’s personal soapbox, one that eventually exposes him as a dinosaur still fighting the old fight (with or without an opponent). While the book portrays Goldstein as increasingly washed-up and pathetic, it also points out that his significant accomplishments are taken for granted by younger generations who have a world of smut available at their fingertips 24/7, in their medium of choice.

Goldstein’s big mouth was both his making and his undoing – that and his vindictive nature, which resulted in the two legal battles that drained his finances from $11 million to zilch, leaving him literally homeless for many years. While it’s easy to laugh off his loudmouthed antics and see them as a necessarily iconoclastic resetting of the rules, the vile public harassment he dished out to a former secretary (who quit because she didn’t want to be yelled at) and his ex-wife and son can’t be dismissed. Stevenson is critical of this; though it’s clear he has respect for Goldstein’s legacy where deserved, he also sees how easily the magazine’s rants degenerated into contradictory messages. From the beginning, Goldstein claimed an affinity with Lenny Bruce, and frequently used harsh un-PC language as a means of teasing the offensive meaning out of cultural trigger words – but in later years, when the magazine prints things like “Nigger-Lovin’ Jews” – as a caption to a caricature of his ex-wife and son fornicating in a 2002 issue of Screw – it’s not satire, it’s outright racism and sexism used in anger over a personal dispute. As Stevenson points out, Goldstein’s innate need to sabotage would turn on himself when he didn’t have a tangible target, and it was at times when the culture was most accepting of him that he tended to bottom out.

While it seems like it might be best accompanied by Goldstein’s own memoirs and a cursory reading of some authentic Screw content (personally I have to thank Cinema Sewer’s Robin Bougie for my own exposure to Screw), Stevenson’s book offers a lot of history and cultural analysis stuffed into a fast, compelling read, peppered throughout with Screw covers, editorials and ads as well as Stevenson’s own tone-setting photos from a 1980s-era Times Square. As a bonus, the Appendix outlines enough film projects – either directly or peripherally involving Al Goldstein and Screw – to warrant an entire Al Goldstein film festival. (If someone doesn’t snatch this free idea I might have to take it up myself…)

December 19, 2013

December 19, 2013  No Comments

No Comments