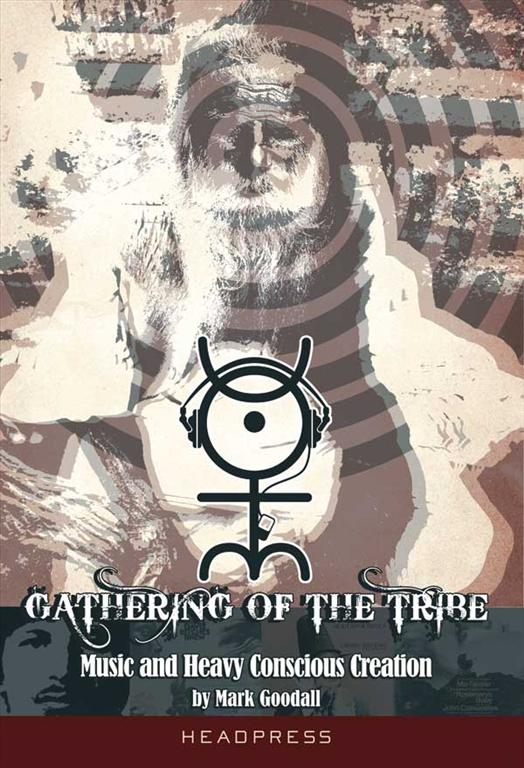

“GATHERING OF THE TRIBE”

GATHERING OF THE TRIBE: MUSIC AND HEAVY CONSCIOUS CREATION – BOOK REVIEW + MIXTAPE

By Mark Goodall

Headpress, 2013

Buy through Headpress HERE.

Buy through Amazon HERE.

Scroll down to the bottom for an exclusive mixtape to accompany this book!

The latest book from author (Sweet and Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Lens, Headpress 2005) and Rudolf Rocker frontman Mark Goodall points out that music’s purpose changed the second we recorded it; like spirit photography, once ‘captured’, a neutering process was set in motion that “killed the aura of sound”. But Gathering of the Tribe is a tightly-curated survey of some of those recordings that manage to let the music loose into the unconscious when it is played back, the way EVP recordings invite spirits into your house when you play them.

The latest book from author (Sweet and Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Lens, Headpress 2005) and Rudolf Rocker frontman Mark Goodall points out that music’s purpose changed the second we recorded it; like spirit photography, once ‘captured’, a neutering process was set in motion that “killed the aura of sound”. But Gathering of the Tribe is a tightly-curated survey of some of those recordings that manage to let the music loose into the unconscious when it is played back, the way EVP recordings invite spirits into your house when you play them.

Divided into chapters including the ‘cosmic sounds’ of post-classical and traditional ethnic music, through improvisational jazz – which Goodall describes as “one of the most effective forms of music in capturing virtual, immaterial and cosmic forces” – weird folk, electronic experiments, sinister soundtracks, hippie drone, satanic psych-outs and guru gatherings, Gathering of the Tribe is a wealth of disparate musical experiments brought together under an intriguing occult umbrella. The book doesn’t presume its readers have a spiritual sensibility; it works equally well as a critical shopping list of weird sounds for the adventurous listener. But where it is most rewarding is in its reification of music as an element essential to stirring the soul, plumbing its obscure depths with a transformative agenda.

In defining ‘occult’ it’s important to remember that despite salacious associations with the ‘dark arts’, the term refers to any kind of arcane or esoteric knowledge, and so the music here ranges from systematically mathematical to free-floating new-age and everything in between. The book touches on Renaissance-era examinations of the occult qualities of music, but its catalogue really begins with Debussy and Satie, whose late 19th century context coincides with the period known for its proliferation of parlour mediums ushered in by the likes of Madame Blavatsy (1831-1891), and fad spiritualism fuelled further by the work of Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) and G.I. Gurdjieff (1866-1949), the latter of whom specifically turned to music for its healing powers.

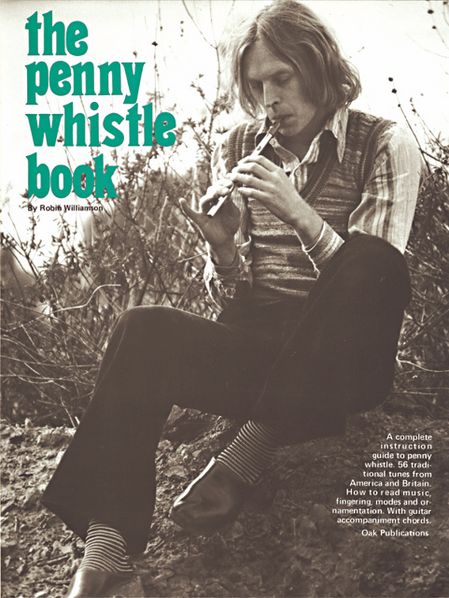

As a teen I had a crush on Robin Williamson because of this picture. The one and only time I ever liked a man wearing clogs.

Where the book really gets going for me is in its third chapter, devoted to ‘freaky folk’. While ‘folk’ traditionally recalls, well tradition, Goodall points out that the artists he’s selected to explore in this chapter – from The Incredible String Band to David Fanshawe to Brian Jones’ Moroccan expeditions with the Master Musicians of Joujouka to The Third Ear Band –do not necessarily subscribe to pat notions of tradition, but explore within it: “It is notable that none of the artists discussed in this chapter are burdened by the ‘authentic folk tradition’,” he says, “a tradition akin to Nietzsche’s conception of both monumental and antiquarian history, narratives which paralyze invention through the looming weight of the historical process.”

Furthermore, these artists combine disparate folk traditions – British, South American, Antipodean, Indian, African – and such hybrids, while perhaps not ‘authentic’ folk by virtue of their very diversity (authentic as in ‘the world you see from your own back porch’), it is a welcome transcendence of those myriad traditions in that they acknowledge the past while reaching for more than that past has to offer, a spirituality with contemporary and personal relevance. Barry Dransfield’s “The Werewolf” – a cover of a 1964 Michael Hurley song, whose Pennsylvania backwoods setting is transposed to the British moors here – was a chilling discovery for me (apparently it was later covered by Cat Power too). Still, The Incredible String Band, whose 1971 album Be Glad For the Song Has No Ending is profiled here, is undeniably rooted in the rich folkloric sounds of Britain (The album is also the soundtrack for Peter Neal’s 1969 film of the same name, originally commissioned for the BBC’s Omnibus program but ultimately rejected as too formalist – or, just possibly, too silly). You can watch the film in the clip below.

The ‘Law of Octaves’ section begins fittingly with G.I. Gurdjieff’s 1962 album Improvisations (Gurdjieff’s cosmological theory gives the section its title) and runs the gamut from Scientology (a frequent topic of discussion in this book) to J.G. Ballard and ODB. I’m not sure I follow this section’s thematic links, but the ODB section by guest reviewer Thomas McGrath proffers a convincing speculation that the proliferation of rappers stemming from the ‘5 Percenters’ offshoot of the Nation of Islam (including the Wu Tang Clan) was in part due to the fact that their catechisms “incidentally enhanced these young persons’ mnemonic and recitative abilities”. He also brilliantly compares ODB to Phil Ochs.

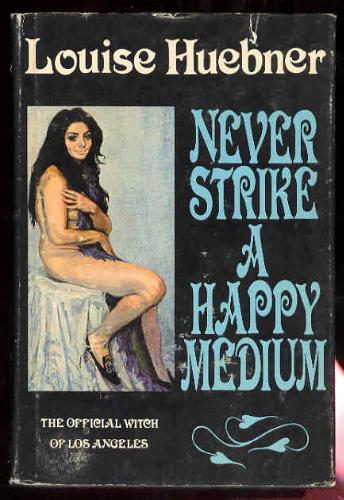

Several witches turn out their own records that are included here, including the “Official Witch of LA”, Louise Huebner, whose spoken word occult LP is backed by an electronic score courtesy of electro pioneers Louis and Bebe Barron (who came to prominence with their all-electronic score for Forbidden Planet), and Barbara The Gray Witch, whose self-titled LP is similarly instructive in nature.

Moondog always stops me in my tracks – there’s no way you can’t engage with it (I admit I’m a jazz lightweight – I always need a hook and his 1969 eponymous album has plenty of ‘em). Speaking of hooks – and skipping ahead to the next section on “Psych-Out and Countercultural Occult” – Ken Nordine’s renowned word jazz LP Colors– made up of 24 pieces, expanded from an original ten commissioned by the Fuller Paint Company as radio spots – is also covered here, with an analysis going beyond the obvious beatnik novelty appeal into the transcendence of colour theory. (see also our interview with Chris Blum, who directed/animated the Nordine-narrated Levis commercials HERE)

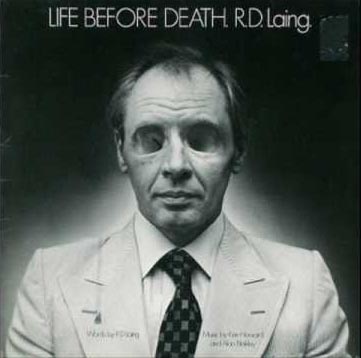

RD Laing’s album Life Before Death (1978) was another of the big surprises of the book for me. The reluctant anti-psychiatry godfather allegedly made the record while drunk, with music courtesy of sometime Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich songwriters Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley. But one of the weirdest connections was discovering through Goodall’s notes that Laing’s book Knots (1970) was adapted for the stage by recurring A Ghost Story for Christmas actor Edward Petherbridge in 1973 (later also made into a short film by David Munro which you can see below). A rather delicious intersection.

RD Laing’s album Life Before Death (1978) was another of the big surprises of the book for me. The reluctant anti-psychiatry godfather allegedly made the record while drunk, with music courtesy of sometime Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich songwriters Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley. But one of the weirdest connections was discovering through Goodall’s notes that Laing’s book Knots (1970) was adapted for the stage by recurring A Ghost Story for Christmas actor Edward Petherbridge in 1973 (later also made into a short film by David Munro which you can see below). A rather delicious intersection.

The subsequent ‘Sorcery in the Cinema’ section addresses the inevitable occult aspects of cinema as a ‘magic lantern’ that allows people to exist in more than one place simultaneously (something I’ve always felt contributes to celebrity-worship in a largely godless society – only ‘God’ and the famous can be everywhere at once). Referencing Gene Youngblood’s seminal book Expanded Cinema, Goodall quotes that cinematic creation is a “process of becoming, man’s ongoing historical drive to manifest his consciousness outside his mind, in front of his eyes.” (Qtd Pg.213-214)

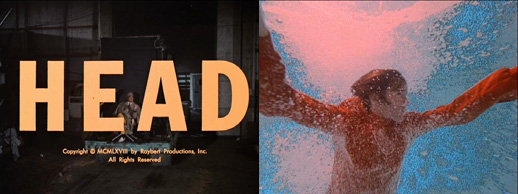

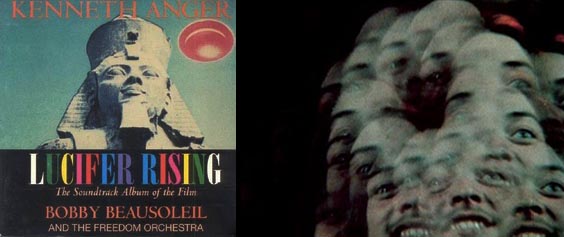

Further to this, he offers that the music used in the films discussed in this section offer an “occult counterpoint” to the images; soundtracks range from Marc Wilkinson’s score for Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw (featured in my ‘Monsters Rule OK’ mixtape HERE) to Bobby Beausoleil’s Lucifer Rising, Popul Vuh’s Aguirre The Wrath of God, The Monkees’ Head, and the scores for Peter Whitehead’s Daddy and Thierry “Pig Fucking Movie” Zeno’s mondo art movie Of The Dead.

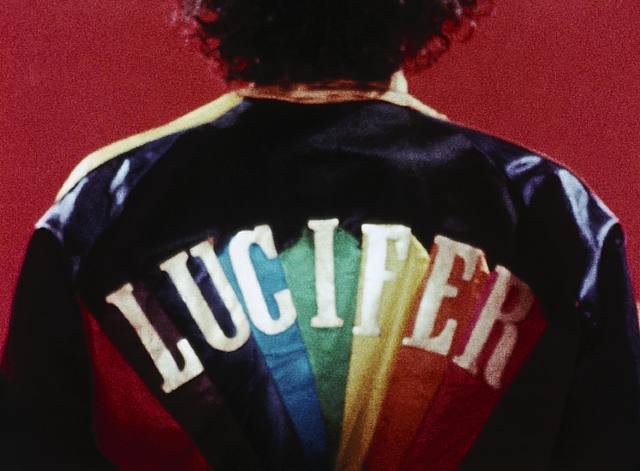

Kenneth Anger’s films and their pop-occultural connections are necessarily given special emphasis in this section. The chapter on former Mansonite (and early Love guitarist) Bobby Beausoleil’s ecstatic score for Lucifer Rising (composed from prison) points out the film’s many connections to Donald Cammell’s Performance, being made at the same time: Cammell appears in Lucifer Rising as the god Osiris, it was produced by Performance co-star Anita Pallenberg (whom Anger described as a “witch”), and stars Marianne Faithfull, who was Pallenberg’s best pal and the girlfriend of Performance star Mick Jagger, the latter of whom would also provide the experimental electronic score for Anger’s 1969 film Invocation of my Demon Brother (Performance and Invocation of my Demon Brother are also both given their own chapters here).The occult vibe running through all these cross-collaborations is palpable and fascinating. And while Jimmy Page’s unused score for the film doesn’t get its own chapter, it does get some ink here.

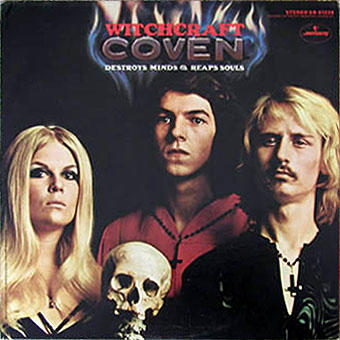

The book doesn’t focus on contemporary music that leans on occult costuming and setpieces as a schtick (i.e. there’s barely a whiff of heavy metal), although some early theatrical Satanist bands like Coven and Black Widow make the cut in ‘The Devil’s Interval’ section – named after the discordant tritone that Goodall alleges was banned by the medieval church. The section centers on music that deliberately calls upon ‘evil’ influences, be they satanic, dark witchcraft and other black corners of occult belief. Groups like Bathory and Coven – who, legend has it, sold their soul to the devil for a hit song (it would turn out to be the Billy Jack theme song ‘One Tin Soldier’) – are expected entries here, but the chapter does a 180 with a surprising serving of post-punk, including The Fall’s sophomore LP Dragnet, Rudimentary Peni’s 1989 Lovecraft concept album Cacaphony (which also manages to sneak in references to MR James , Poe, Shelley and others) and The Monochrome Set, who are given a chapter guest-penned by headpress honcho David Kerekes specifically in light of their song ‘The Devil Rides Out’. The latter not only bears the same name as Dennis Wheatley’s beloved novel-cum-Hammer film but is also written and sung in Enochian – a 16th century occult language!

The book doesn’t focus on contemporary music that leans on occult costuming and setpieces as a schtick (i.e. there’s barely a whiff of heavy metal), although some early theatrical Satanist bands like Coven and Black Widow make the cut in ‘The Devil’s Interval’ section – named after the discordant tritone that Goodall alleges was banned by the medieval church. The section centers on music that deliberately calls upon ‘evil’ influences, be they satanic, dark witchcraft and other black corners of occult belief. Groups like Bathory and Coven – who, legend has it, sold their soul to the devil for a hit song (it would turn out to be the Billy Jack theme song ‘One Tin Soldier’) – are expected entries here, but the chapter does a 180 with a surprising serving of post-punk, including The Fall’s sophomore LP Dragnet, Rudimentary Peni’s 1989 Lovecraft concept album Cacaphony (which also manages to sneak in references to MR James , Poe, Shelley and others) and The Monochrome Set, who are given a chapter guest-penned by headpress honcho David Kerekes specifically in light of their song ‘The Devil Rides Out’. The latter not only bears the same name as Dennis Wheatley’s beloved novel-cum-Hammer film but is also written and sung in Enochian – a 16th century occult language!

Black Widow on Germany’s ‘Beat Club’:

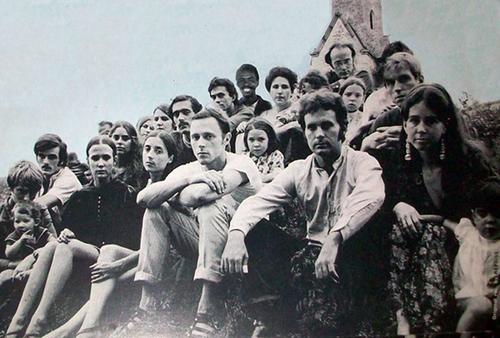

The ‘Mindfuckers’ section is devoted predominantly to the various ‘house bands’ of alternative lifestyle collectives (aka cults), including the Boston-based Fort Hill Community (aka The Lyman Family, after their controversial figurehead Mel Lyman) – whose famous members included experimental filmmaker Bruce Connor (known for Devo’s ‘Mongoloid’ video), Zabriskie Point star Mark Frechette and Crawdaddy Magazine founder Paul Williams – The Source Family, The People’s Temple, and of course, The Manson Family. The section extends to ‘outsider’ artists, counting the likes of Nico and Molly Drake (mother of Nick and Gabrielle Drake) among that number. I’m not certain I agree with the categorization, but many of these sections feature artists that could easily fall into another category, creating a criss-crossing web that just complements the overall nature of the book.

After one last section focused on various forms of experimental electronica, from space-age to industrial to power electronics (including Basil “Abominable Dr. Phibes” Kirchin’s States of Mind album, commissioned for a psychiatric conference and the closest the book comes to addressing the Auroratone phenomenon) , the book just ends abruptly, with no wrap up; perhaps Goodall thought of the book as a reference guide that wouldn’t be read all at once but I admit it was disappointing that for such a heady tome, there was no come-down.

Still, I loved this book. There were enough familiar topics to hook me in, but in addition to its consciousness-expanding and historical insights, it operated as a vital guide through some of the world’s most challenging sonic experiments. Exciting connections appeared throughout, which meant that while reading I was constantly inspired, making notes of obscure tangents to follow once the book reached its end. Because I wanted to make a mixtape to accompany the book (scroll to the bottom of the post for the mixtape), this became a great way to read what could otherwise have been a daunting array of new information to digest all at once. But as I read each chapter, I listened to the album in question (provided I could find it), which not only added to my empathy with the heavy concepts those albums propose, but was also just an enjoyable way to commune with the book.

****

GATHERING OF THE TRIBE by Kier-La Janisse on Mixcloud

NOTES ON THE MIXTAPE:

LOUISE HUEBNER “Introduction – Gods” (excerpt)

“That the modern witch is alive and well in popular culture today is thanks largely to the throbbing and zestful efforts of Louise Huebner and this fine contribution to occult out-there conscious creation.” (Pg. 171)

PEOPLE’S TEMPLE CHOIR “Welcome”

“The sound resembles a plastic Disneyland version of joy and the words take on a sinister feel knowing the fate of these children.” (Pg. 393)

BLACK WIDOW “Come to the Sabbat”

“It is one of the most effective satanic rock LPs ever recorded, far more interesting than anything by the turgid Black Sabbath.” (Pg. 297)

ROBBIE BASHO “Venus in Cancer” (edit)

“This sense of drifting timelessness characterizes the spirit of heavy conscious creation.” (Pg. 96)

THE MONOCHROME SET “The Devil Rides Out”

“The Monochrome Set’s use of catchy pop songs behind lyrics often dark and bizarre was a little subversive.” (David Kerekes, Pg. 335)

GIL MELLE “Andromeda” (from The Andromeda Strain)

“When it comes to proto-electronica at its most austere and discordant, it is the bleak soundscape created by Gil Melle for The Andromeda Strain that leaves an indelible imprint on the memory banks.” (Pg. 281)

DELIRED CHAMELEON FAMILY “Raganesh” (from Visa de censure’X’)

“[Clementi’s] films are brilliant examples of the ‘head’ film, external projections of the inner mind, but shorn of the pseudo political sloganeering of many countercultural works.” (Pg. 286)

PAUL GIOVANNI “Gently Johnny” (from The Wicker Man)

“the complexity and nuances of the score, not to mention its unconventional nature mean that it is more than just a genre of folk music; it becomes in fact a gateway into the psychology of the meaning of sacrifice.” (Pg. 120)

GRAHAM COLLIER “Day of the Dead” (excerpt)

“In adapting Malcolm Lowry’s classic 1947 novel Under the Volcano for the twelve-piece jazz group, British composer and pianist Graham Collier has virtually connected the structure and style of literary technique to that of musical arrangement.” (Pg. 44)

WHITE NOISE “Love Without Sound” (edit)

“…fear develops out of a sparse sonic space, within which components of the unknown assault your senses.” (Pg. 432)

OL’ DIRTY BASTARD “Rawhide”

“Return to the 36 Chambers: the Dirty Version itself – a chaotic, carnal, funky and psychedelic record that bristled with 5 Percenter imagery –struck a similar balance of sacred and profane elements, a record Rick James might have made if endowed with a throbbing third eye.” (Pg. 150)

DAVID AXELROD “The Sick Rose”

“Axelrod attempts to transport an audience through sound into another world, an Eden where the human spirit is unfettered by the machinations of industrial processes and the death of the natural world.” (Pg. 194)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY “Prelude a L’apres-midi d’un faune” (excerpt)

“one of the most important and revolutionary works in the history of sound” (Pg. 9)

R.D. LAING “Four”

“Laing was a therapist, a witness to his own family madness, who was not afraid to go straight into psychosis himself and was prepared to try to get out the other side again.” (Pg.199)

MOONDOG “Bird’s Lament”

“To this day Louis Hardin’s work and his unique ‘sound world’ have not been surpassed in terms of sheer inventiveness and free , sincere expression.” (Pg. 166)

CHARLES MANSON “Look at Your Game Girl”

“Manson’s music, like most of what he did, is hated and feared.” (Pg. 386)

JOHN FAHEY “The Dance of Death” (edit, from Zabriskie Point)

“As a vast site of mystical power, [Zabriskie Point]naturally attracted the attention of Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni, famed for using vast spaces to represent the human condition, in his quest to make a film about the American counterculture of the late 1960s.” (Pg. 239)

YA HO WA 13 “Ya Ho Wa” (edit)

“Penetration captures a moment of creation that would never be repeated. This is the beauty and occult nature of free-form sound.” (Pg. 391)

ALICE COLTRANE “Universal Consciousness”

“Universal Consciousness – one person’s profound journey into heavy conscious creation – surpasses the work of the avant-garde jazz musicians of the 1960s.” (Pg. 49)

RUDIMENTARY PENI “Horrors in the Museum”

“a coherent yet deranged tribute to Lovecraft.” (Pg. 317)

ERIK SATIE “Vexations”

“Engagement with the piece as player or listener leads to awareness of some secret form of knowledge” (Pg. 13)

BOBBY BEAUSOLEIL “Second Movement” (from Lucifer Rising)

“Around Anger’s flowing sequences Beausoleil’s music swirls and enchants, a heavy psychedelic trip of the occult imagination.” (Pg. 231)

STOCKHAUSEN “Stimmung Model 3”

“The work is about reawakening the sensations created by the great religions of the past using modern elements and vibrations that are not necessarily connected with any established sacred path…it is music for a post-apocalyptic age.” (Pg 16-17)

JIM KWESKIN “Old Rugged Cross”

“The overall effect of all this is akin to the terrors of the past lurking in Michael Lesy’s book Wisconsin Death Trip” (Pg.379)

OLIVIER MESSIAEN “Psalmodie de l’ubiquite par amour” (excerpt)

“Messiaen spoke of his ‘horror of cities’ and this musical movement appears to be an expression of that fear.” (Pg 22)

NICO “No One is There”

“Nico’s songs…are the rustic compositions of a true outsider, like nothing else produced in the history of music.” (Pg. 425)

CHANGES “Fire of Life”

“Fire of Life uses the ethos of the modern age to magnify and recreate ancient and traditional modes of communication, filtering and altering esoteric ideas and beliefs where necessary.” (Pg. 310)

NICK CAVE AND THE BAD SEEDS “Tupelo”

“Cave makes the vividly dramatic suggestion that the birth of Elvis Presley, coupled with the death of stillborn twin, Jesse Garon, was the product of a supernatural, if not apocalyptic, event horizon.” (Mick Farren, Pg.357)

THE LYMAN FAMILY WITH LISA KINDRED “Jesus Met the Woman at the Well”

“The music of The Lyman Family was a curious blend of the ancient American past and bold futurism.” (Pg. 372)

BARRY DRANSFIELD “The Werewolf”

“evok[es] both the ancient myths of the danger and beastliness of male sexuality and the lurking fear of the rural horror film.” (Pg. 92)

THE MONKEES “Porpoise Song” (from Head)

“The sense of elegy and lost opportunity mingle in an extraordinary 2.57 of music” (Pg. 276)

December 29, 2013

December 29, 2013  No Comments

No Comments