Passing on the Genre Gene (Part 1)

To coincide with our upcoming anthology book KID POWER!, The CineFamily’s Bret Berg viagra canada generic talked with various filmmakers about introducing their kids to cult cinema. We’ll posting new interviews throughout the duration of our Indiegogo Campaign to raise printing funds, which you can see and contribute to HERE.

*****

Decades after the fact, the buy levitra in india key movie-watching moments that shook my childhood spine with a freaked-out, reverb-coil KLANG! still have a lingering emotional resonance—and still call up incredibly vivid tableaux containing every last detail of the conditions under which I viewed them. Even from a youth spent fully immersed in the weird and the fantastical, these random snippets were seismically whacked. Looking back, it was body horror all the way that got me: RoboCop’s melting toxic waste man, the henchman from Swamp Thing unknowingly dosed with mutant sauce that convulses him into a shrunken piglet dude, “Uncle Phil” from Fresh Prince of Bel-Air getting the fingers blown off clean off his hand in Nightflyers.

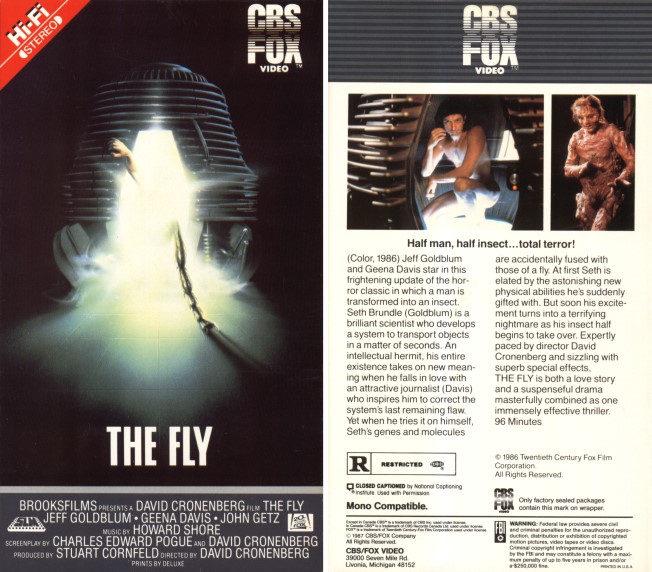

The most potent freeze-frame canadain cialis of my youth was found in the enormous horror section at Video 101, the funky, brown-carpeted strip mall rental joint my parents dragged me to. On the VHS back cover of Cronenberg’s The Fly, there’s an image of Goldblum in full-on naked Brundlefly mode, caught in mid-stride as if in a Saturday Night Fever strut, with contortions of bone protruding through his skin, and individual fingers fused together. This solitary snapshot fucked me up for an entire decade (Chris Walas, I cialis brand only raise my glass in a toast to the grody power of your makeup effects).

Today, a healthy amount of my contemporaries who were weaned on the same outré viewing material that I grew up with are now having kids of their own. They’re generally doing a kick-ass job of raising bright and intriguing tots, but I often wonder—since the realm of cinefantastique was so formative to us, how much are they letting their little ones play with it, considering we were best served by our own parents never paying too close attention to what we were watching?

Today we ask Daniel Noah, Producer of Cooties, Open Windows and McCanick:

Daniel Noah: My parents made time limits–I could only watch a certain amount of stuff per day. But my grandparents were a little bit more liberal. My grandfather was a really hip, progressive guy, a jazz musician. When I was really young, he’d show me movies like Dog Day Afternoon, films that were above my “pay grade” intellectually. I remember being really titillated by the feeling of seeing something truly adult, and the sensation of not fully being able to penetrate it was very thrilling to me.

My grandfather weaned me on the Universal horror films. I don’t remember being scared by them, per se; they were more of an emotional experience for me. Looking back as an adult, I’m always inspired to see that, in Universal horror, the monster’s almost always the most sympathetic character.

I’m a fanatic, I collect horror paraphernalia. When my daughter was born, I cleared out all my figurines and weird art, because I just didn’t want to scare her. Completely on her own, she ended up being drawn to the Universal monsters, but I don’t remember how she first got exposed to them. As a father, it was thrilling to see it was somehow genetic, that she was having the same emotional relationship to it that I had. She’s interested in the minutiae of their stories. She refers to the Phantom of the Opera as “Eric.” When she plays with the Universal monster figures I got her, the Phantom isn’t the bad guy. He merely loves the girl, who doesn’t love him back.

Bret Berg: Do you have a sense in advance of what kind of material will upset her, now that she’s in the kindergarten stage?

Daniel Noah: It’s still trial-and-error. I find, honestly, that some of the most disturbing imagery and ideas that she gets exposed to are from cartoons that are supposed to be for kids, that are produced today. Really violent, horrible stuff. I don’t know the names of all these shows, but I’ll see them and think “Oh my god, I don’t want that in her head!”

You’ll show your kid something, and they’ll let you know right away if they’re not ready for it. Their reaction is not mysterious. They’ll start dancing around, jump in your lap, or get antsy. I’ll get a real quick feeling if it’s “too soon”, I’ll turn whatever it is off—and I’ll try it again in a year. The second time, she might be ready.

Bret Berg: When I was around her age, I would get intensely disturbed and leave the room whenever I saw Leonard Nimoy as Spock from the ‘60s Star Trek. Maybe it was something about his stare. Are these “nightmare food” moments are necessary for a child’s development?

Daniel Noah: They’ve gotta be, right? So many people have these moments. But what if you’re one of those people that genuinely doesn’t enjoy that? Are those experiences as valuable? I’m thinking of certain people I know that hate horror movies, and I don’t know that having those moments were beneficial to them.

As someone who makes horror movies, a typical response I hear from laypeople not in the industry is “I just don’t like to be scared.” I’ve come to accept that there’s two kinds of people: those that derive some pleasure from fear, and those who don’t. I hate rollercoasters, and would pay a $1,000 not to be flung hundreds of feet in the air. That’s horrible to me, that’s my version of “I don’t like horror films.” But people say “That’s the thrill, you get to experience danger in a safe context, where nothing bad is going to happen.” A horror movie gives you an opportunity to confront that very same thing. It’s very empowering.

****

Bret interviewed producer Rock Demers about kiddie nightmare-fueler THE PEANUT BUTTER SOLUTION for our KID POWER book.

April 11, 2014

April 11, 2014  No Comments

No Comments