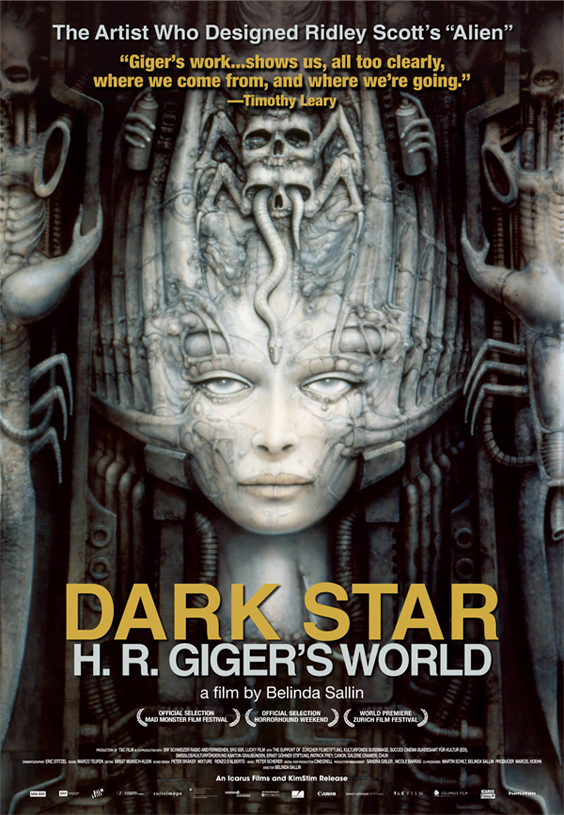

“DARK STAR: H.R. GIGER’S WORLD”

A warm, sober peek at the last century’s most popular dark surrealist, id tripper and master of monochrome, it would be fair to describe this film as the portrait of a tired, old man. Director Belinda Sallin was permitted to sit in on the day-to-day at Giger’s house – endearingly, his friends and family call him “Hans Ruedi”, first name and middle nickname in one breath – and the shoot concluded just prior to the Swiss artist’s death in May 2014. Throughout the film he is struggling, slow, quiet – health-wise a visible step down from Jodorowsky’s Dune, my top doc of 2013, wherein Giger discussed his pre-production work on the greatest best online generic levitra science fiction picture never made. Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World can’t help but carry a get-in-there-while-we-still-can necessity, because it was not the optimal time to tell this tale, it was simply the only time left.

From the quiet, calm opening, a tentative walk through the statue-laden grounds of Giger’s property, the film bares a resemblance to the 2009 documentary Anne Perry: Interiors, a contemplative look at the popular crime novelist (who in an earlier life, was one-half of the teenage matricide duo that became the subject of Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures). It takes over four minutes into Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World before a word is spoken, and even then, Sallin’s film is contained almost entirely within the walls of the artist’s home/office and surrounding grounds, where close friends, family and staff overlap roles in service of the Giger business machine, earning viagra fedex money to reinvest in new projects. Like Interiors, the central, aging artist speaks relatively little, the film building its narrative on the insights of those who live, work, and breath alongside him day after day, and remain committed and awed.

Giger’s house is a vast maze of art pieces and books stacked everywhere, especially the bathtub (which was emptied once, apparently, to be promptly filled with an antlered ibex skull). It’s a house where stepping over a lion spine outside the front steps – reference material for Sil from Species – is not totally unusual. We get to ride with Giger on his functional ghost train that weaves through the overgrown bush of his yard, demoness statues and bloated cherub baby faces and vaginal tunnels around every twist and turn. It nicely illustrates the playful commonality of creepy in Giger’s world.

Not all footage is new – archival footage shot by Giger’s ex-wife Mia Bonzanigo as Giger steps through his in-progress sets of the alien ship and space jockey from Alien is monumentally cool. Footage from Fredi M. Murer’s Passagen (1972), a 50-minute film for German television, focuses on young Giger at work and walking the Swiss alps at his family’s cottage retreat (a location we return to, in present day). There are clips from 2003 of the construction and opening of the H.R. Giger Museum’s Giger Bar at the Château drug generic propecia St. Germain in Gruyères, with the artist in much sprightlier shape a decade prior.

The film could’ve been called Giger and His Women – clearly the man maintained a healthy discourse with the multitude of women in his life, past and present, as numerous wives and girlfriends make on-camera appearances and provide many of the film’s most illuminating and off-the-cuff details. Like his wedding proposal to Bonzanigo, shouted impromptu from the shower after she fielded a journalist’s phone call, complaining that if she’s his wife the press will listen to her and not just treat her like a groupie. Going back further, the suicide of Giger’s longtime girlfriend and muse Li Tobler in 1975 (the female face in many of his early, famous works), still haunts the artist deeply, and is the subject of the film’s most emotional interview, along with equally grim, matter of fact reflections from Li’s brother.

Carmen Maria Giger, Hans Ruedi’s second wife until death and director of the H.R. Giger Museum, recounts how a six-year-old Hans became obsessed with a mummy on display at the Raetian Museum in Chur. Initially terrified and mocked for his fear by an older sister, he returned again and cialis online us again to study it. This death-object became the seed that defined his work – the body of a princess, the feminine and the sublime. Bones, fetishism, the sense of eternity and the particularly Egyptian extravagance for a crafted death perfection. His magic mix of eroticism, mechanics, morbidity and rebirth began here, including his creative process – after being tormented by a vivid, fearful vision, he conquers that fear by returning to it repeatedly and expulsing it as art. Early in the film, Giger pokes through his collection get viagra without prescription of human skulls and show us his first, a gift from his father, also from when he was six years old.

As a metalhead, a shock moment (that is probably common knowledge to some) was learning that Tom G. Warrior of Celtic Frost and Hellhammer was H.R. Giger’s assistant for years. Despite the close company over a long period of time – Giger supplied three album covers for Tom, including Celtic Frost’s 1985 opus To Mega Therion – the Swiss metallion is visibly nervous around his employer and favourite artist and anxious for his approval. They first met when Tom looked up Giger’s name in the phonebook and cold called his hero, after numerous label rejections for Celtic Frost’s pioneering death metal racket. According to Tom, “This guy who just won an Oscar was the only one who took us seriously.”

It’s funny to see the metal legend methodically work through a stack of paperwork, while next to him is Carmen Maria’s mom – Giger’s mother-in-law – at her own desk with her own stack of paperwork. Meanwhile, the house cat Müggi III (presumably, the heir to Müggi I and II) wanders around the house and investigates. Downstairs in the basement, a recently hired new manager organizes Giger’s lithographs. Later Giger bemoans in conversation with another ex-assistant/ex-girlfriend that having a house so tidy makes him uncomfortable and is “so bourgeois”.

When the film shifts from this close-knit household community into art shows and fandom, the result is initially a little rocky – the curator of an exhibit in Austria is a bit of a dud, looking, acting and hogging the conversation like, well, a gallery curator cliché. He infers from Giger’s work what we’ve already interpreted ourselves. Yet when Sallin returns to her more comfortable camera position, hanging back and observing, we feel claustrophobic watching the aged legend be mobbed by tattooed metal ragers, goths and superfans gawking at their king. One big man begins to cry after Giger signs his copy of Alien Diaries, released last year. Another man walks up and wordlessly unbuttons his shirt to show off a monstrous Giger-inspired back piece. Gauged by Hans Ruedi’s reaction, this is obviously a common occurrence.

H.R. Giger proved beyond doubt that any id indulgence can be canonized by the mainstream – as long as it’s filtered though a Hollywood blockbuster. It’s hard to imagine anyone in the last 40 years who doesn’t have at least a passing familiarity with his style and tone, and a reaction to it. A lifetime of smart commerciality plays a large part in this, and we get to watch the insides of that operation. Building a career and fame from mass market poster sales rather than high art exhibition, then later merging the two, is certainly one of the secrets to his genius and pervasiveness.

Committed in his belief that death is an end without an afterlife, Giger says, “I’ve seen everything I wanted to see. Everything I wanted to do or show, I’ve done it. I don’t need any more than that.” It doesn’t get more final than that.

R.I.P. H.R.G., long may you haunt us.

May 11, 2015

May 11, 2015  No Comments

No Comments