Fantasia 2015: “MANSON FAMILY VACATION”

As I’ve learned from my years travelling the festival circuit, there are more than a few dyed-in-the-wool horror fans who are adopted. We tend to generic propecia online within canada find eachother. And last Saturday afternoon many of us found ourselves emerging from the Fantasia Film Festival’s screening of J. Davis’ Manson Family Vacation, more than a little shaken.

At Fantasia it’s those genre-defiant oddities that most often sideswipe you. What had been positioned as an indie comedy about two brothers on a road trip – one an uptight lawyer (Jay Duplass) and the other a nomadic, artistically inclined Charles Manson obsessive (Linas Phillips) – turned out to be quite a heavy drama about not only troubled relationships between siblings, but the kinds of genealogical bewilderment[i] and attachment issues that plague adopted kids.

A beautifully sun-bleached opening depicts the long-haired canadian pharmacy viagra and disheveled Conrad (Phillips) hitchhiking his way to LA for a surprise visit with his estranged brother Nick (Duplass), who is a straight-laced professional family man. The two couldn’t be more different, which is explained with the revelation that Conrad was adopted by parents who believed themselves unable to conceive. An unexpected biological pregnancy a few years later brought Nick into the picture, and he price of propecia from canada immediately became the favored child. As Conrad recounts to Nick’s young son Max, “they just kind of forgot about me.”

Their strained relationship is tested further by Conrad’s insistence that they take a day trip to visit Manson murder locations throughout the city – Nick doesn’t want to go, but is prodded by his sympathetic wife Amanda (Leonora Pitts) to respond to his brother’s obvious attempt to bond, however suspect the method.

Their first stop is the gate on Cielo Drive that once led to the now-razed-and-rebuilt home of Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski. Nick is disturbed by Conrad’s gleeful recounting of the gory details of the murder, but is thoroughly mortified when Conrad poses for a selfie, unzipping his hoodie to reveal a Charles Mansion T-shirt beneath.

The disastrous daytrip is extended to a road trip to Death Valley, where Conrad claims to have a job lined up with a propecia cheap secretive environmental group. And this is where things start to get really weird and heavy in ways you’ll have to watch the film to discover.

Interestingly, the Cielo Drive property is now supposedly owned by producer/writer/director Jeff Franklin, best known to horror fans as the screenwriter of the 80s comedy Summer School, which gave us high school gorehounds Chainsaw and Dave – beloved characters who would nonetheless likely share Conrad’s preoccupations.

The connection to Chainsaw and Dave is important. When Summer School came out in 1987, the characters gave even Fangoria magazine cause to cover the otherwise saccharine film; at the time there had been very few horror fans depicted onscreen – Morgan Stewart’s Coming Home debuted the same year, preceded by Lance Kerwin in Salem’s Lot (1979) and Corey Feldman in Friday the 13th Pt IV (1984). As order soft viagra online such, young horror fans reveled in these characters that normalized their morbid interests and even heroicized them.

Manson Family Vacation’s power among a genre audience is that many of these fans can undoubtedly see themselves in Conrad – many genre fans go through at least a superficial Manson-obsessive phase at one time or other (the framing story of Jim Van Bebber’s Charlie’s Family addresses this with the “Charlie Don’t Surf” scene). I have never visited the Tate or LaBianca houses, or the remains of the Spahn ranch. But I have always wanted to – even though I know to do so is to trivialize someone else’s very real pain. Horror fans have a knack for compartmentalizing. As a kid who developed morbid fascinations early on, I could relate to Conrad’s need to seek out powerful emotion in strange places to counteract the distance from family members who think he is at best a flaky burden and at worst a sociopath.

To be fair to Nick, Conrad is annoying – deliberately confrontational, lacking in empathy or tact, driven to act out by a persecution complex that has saddled him since childhood. He is a handful. Worse, as far as Nick is concerned, is the fact that his son Max seems enamored with his troubled uncle. We first meet Max when he is sent home by a teacher who expresses concern after he is found drawing pictures of people bleeding from their orifices. When Max spies Conrad’s worn hardback of Helter Skelter, he immediately gravitates to the graphic murder images, expressing excitement that solidifies Nick’s belief that Conrad is a bad influence on the kid. He won’t admit that what really frightens him is his own inefficacy as a father, that he is as alienated from his own son as he is from his brother – and that the two are bonding over some bad juju that Nick can’t understand.

Death-obsession in kids is a normal developmental phase, but while Max is clearly working out some issues related to the passing of his grandfather – whose funeral Conrad didn’t attend, thereby deepening the rift between himself and Nick – Conrad’s issues are bolstered by the fact that he is adopted and felt rejected by his adoptive family in favour of their biological son. His mythologizing of the Manson Family is not uncommon for kids who have troubled relationships with their own families – indeed, that’s how many of those youths ended up in the Manson Family in the first place. Adopted kids are especially susceptible to this because they often grow up with a feeling of disconnection from the concept of ‘family’ and yet an intense need to share in what they think is a privilege of the biologically related. While not all adopted kids have the same experience and many grow up without any signs of psychopathology, Conrad is the textbook example of what has controversially been called “adopted child syndrome” (not recognized by the DSM IV): genealogical distress, attachment disorders, nomadic tendencies, defiance of authority and anger management issues.

My brother is the biological son of the parents who adopted me. Another of my adopted colleagues who saw the film grew up in the same context. And our own issues mirrored Conrad’s almost exactly. I grew up jealous of my brother’s biological connection to my parents and what I perceived as their favouring of him, no matter how many times my mother joked that “we were stuck with him, but we chose you!” As a kid I watched horror films, loved true crime stories and reveled in the gory lyrics to songs like “Blood on the Saddle.” By the time I was 12, I was a habitual runaway and spent most of my teen years in group homes, foster homes or juvie. I still can’t stay in one place long. Like Conrad, I’m seen as a ghoulish influence on my brother’s kids – to this day I’ve never been allowed to babysit. Presents I buy them are deemed inappropriate and put high on a shelf out of reach (I know a kid who learned their alphabet from reading The Gashlycrumb Tinies, so how bad can it really be?). Thankfully I now have a great relationship with my brother but it took us a long time to get there.

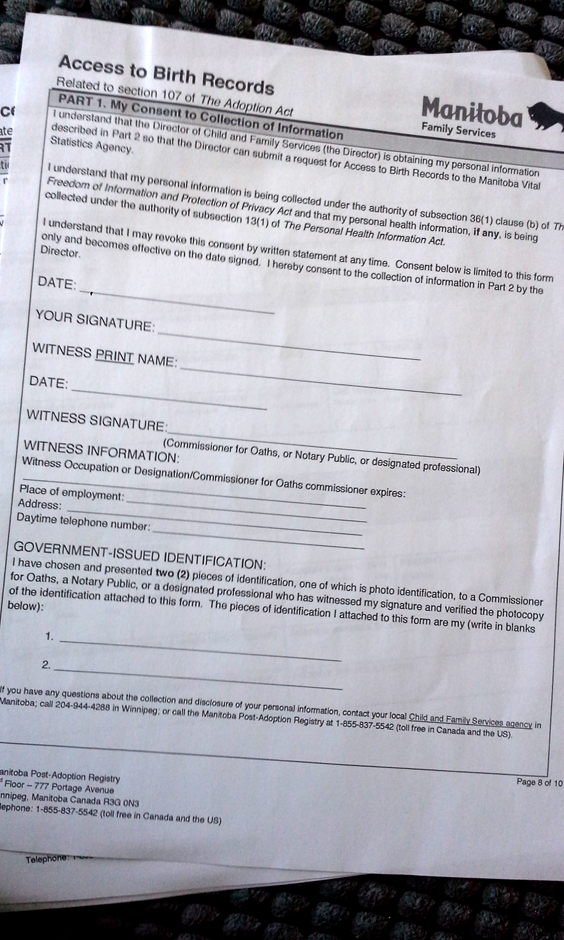

After everything that occurs in the film, Conrad’s reassurance to Nick that “no matter what happens, I’ll still be your brother,” defuses the anxiety that has been building to the film’s climax, and for us adoptees in the audience, this was the moment that wrecked us. Because this is the primary anxiety in adopted families – that there lies this chasm between the artifice of “family” created by the adoption process and the “real” family that is out there somewhere, whom most of us will never know. It’s the elephant in the room; adopted kids live with this palpable sense of a parallel universe where they could easily have had a very different life, and that the only difference between one life and the next is the filling out of a form. And when you reach adulthood, there is the promise that another bout of paperwork could reverse the decision made all those years ago. What happens then?

But an interesting thing happened after the screening. One of my adopted friends admitted he had never even spoken to another adopted person about the experience of being adopted, and that he had long ago abandoned the idea of searching for his birth parents until this very discussion lit that flame again. As for me, there’s a form waiting to be filled out, that I’ve been staring at for two months with a mix of anticipation and fear of repeat rejection. Once I fill it out, something big may or may not happen. But to my brother I’d just like to say, no matter what happens…you’ll still be my brother.

[i] This is a term coined by psychologist H.J. Sants in the 1964 paper “Genealogical Bewilderment in Children with Substitute Parents,” published in the British Journal of Medical Psychology 37, Pgs 133-141.

August 9, 2015

August 9, 2015  No Comments

No Comments