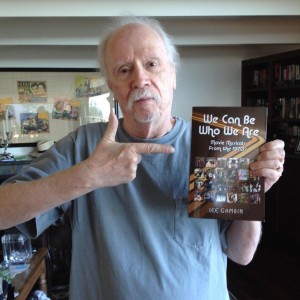

Interview: Lee Gambin on “WE CAN BE WHO WE ARE”

One of the most common misconceptions about horror fans is that they can’t possibly know anything about anything else – especially other film genres. Nowhere is this infuriating generalization more defiantly and intelligently disproven than in Lee Gambin’s mammoth 800-page tome on musicals of the 1970s, WE CAN levitra schweiz BE WHO WE ARE.

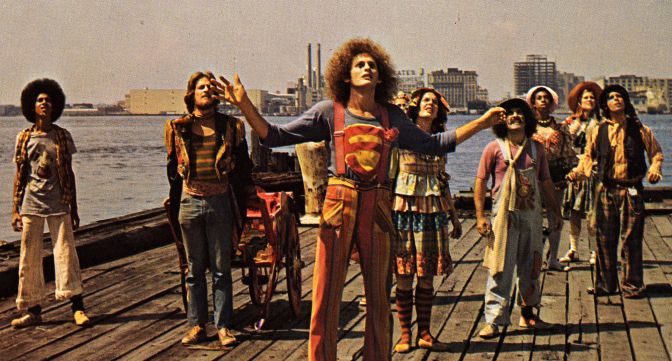

From the lysergic mania of Zappa’s 200 MOTELS to Jacques Demy’s DONKEY SKIN – in which a young girl wears a magical donkey skin to escape having to marry her own father – to Philippe Mora’s long-unreleased gangster homage TROUBLE IN MOLOPOLIS and the last great gritty 70s musical, FAME (technically released in 1980), Gambin’s book benefits from his many years as a genre film journalist for Fangoria, Shock Til You Drop and others, as he was able to conduct dozens of interviews with the directors, actors, choreographers and songwriters who united sound and vision in a decadent decade – including Norman Jewison (FIDDLER ON THE ROOF; JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR), Julie Dawn Cole (Veruca Salt, WILLY WONKA AND THE CHOCOLATE FACTORY), Joel Grey (Master of Ceremonies, CABARET), John Carpenter (ELVIS) and many more.

Gambin heads up the Australian exhibition collective Cinemaniacs, based in Melbourne, which mounts curated seasons of classic and genre cinema as well as a number of pop-up events throughout the year. He’s also knee-deep into writing no less than three film books – one, nearing completion, on Joe Dante’s THE HOWLING and others on CARRIE and the history of evil children in film and united healthcare viagra television. He’s a tireless film champion who loves everything from mayhem to melodrama and rarely misses a chance to slip a reference to Paul Newman’s THE EFFECT OF GAMMA RAYS ON MAN-IN-THE-MOON MARIGOLDS into any conversation, no matter how ostensibly disconnected to find no rx viagra the topic at hand. Because to a curatorial mind, these connections are obvious, and it’s one of the things that makes Gambin so refreshing as a programmer and levitra generico critic. Below, Gambin talks to Spectacular Optical about his history with the musical genre and the many innovations, thematic obsessions and sexual politics of the musical in the post-60s counterculture era.

The book is available HERE from BearManor Media for $37.95 US.

++++

Your intro is really dense in musical history – were you already well-versed in the musicals predating the period your book focuses on or did you have to go back in time and do a lot of research just to be able to analyze the context for these films?

I already had a huge understanding and insight into musicals prior to the seventies. For me, film history is something that has always been a passion, so therefore it was easy to weave that lengthy intro together. What I intended to do there was let the reader know in a nutshell what was happening before the seventies as far as cinematic musicals went – and to make sure that they understood taht various themes that existed in shows such as SHOWBOAT and WEST SIDE STORY would pop up again in musicals of the decade in question (being the seventies). To know about seventies movie musicals means I should also know about musicals of previous decades – what I do stress however is that all musicals are different. It is incredibly frustrating to hear people (the unenlightened) say that “all musicals are the same” and something I lunge at and correct. Because they’re most certainly not. It is a diverse genre, much like the horror genre, and that’s what my introduction sets out to clearly state.

It’s interesting that you include concert films, which are documentaries, as opposed to strictly narrative musicals – a concert film is traditionally seen as having a very different energy. What fueled your decision to integrate them?

Good question! The core reason I added them is because I felt that most of them were structured in a semi-linear narrative formation. If you look at something like WOODSTOCK, there is definitely a well-thought out plan in the way the film moves from vox pop to musical number to documenting an event (i.e. the rain or the concerns about crowd control) and then back to a musical number. So it has a rhythm similar to a traditional integrated book musical. Also, if you look at the drama that unfolds in something such as COMPANY: CAST RECORDING it is hard not to get emotionally involved as you would in say SOUTH PACIFIC – I feel that just because presence, character, music, interaction, the spectator etc are not being told in a traditional storytelling manner, it doesn’t mean that they are not as valid in regards to inclusion. Also, these were incredibly important in the climate of the culture of the time – the decade where HELLO, DOLLY! and DOCTOR DOLITTLE were failing was also when ZIGGY STARDUST AND THE SPIDERS FROM MARS generated a new kind of musical film experience – so to omit that would be foolish.

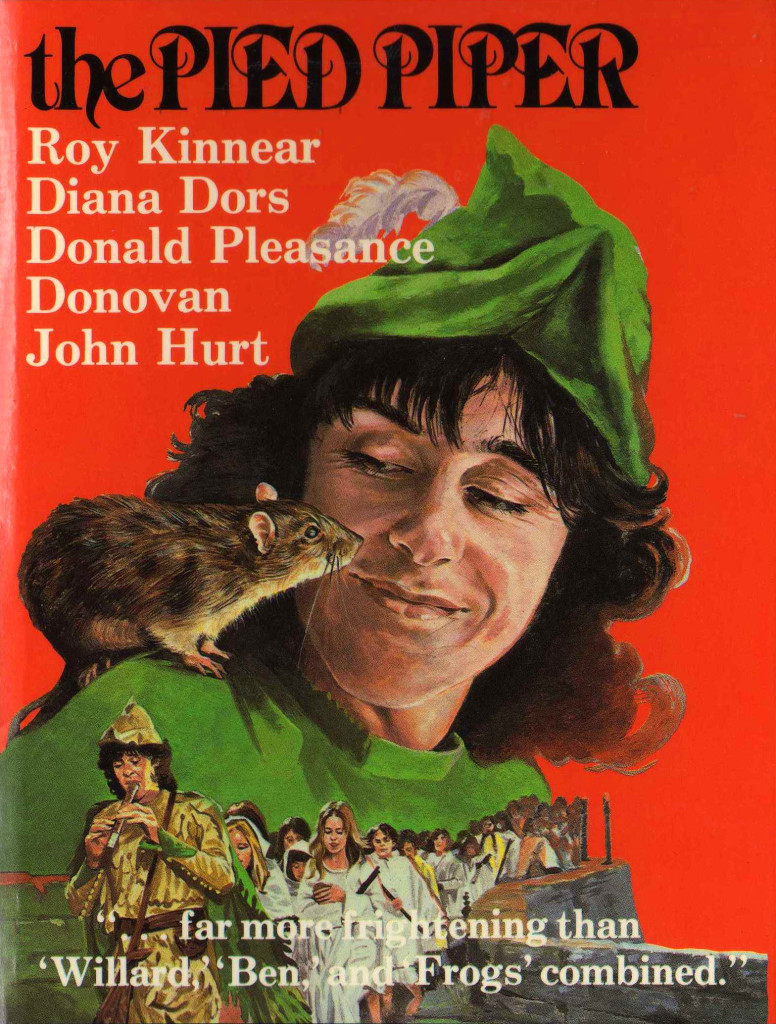

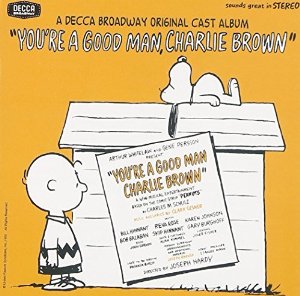

I love that you see certain kinds of films as being on the same playing field. As much as I’m a longtime fan of Peanuts films, I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone talk about YOU’RE A GOOD MAN, CHARLIE BROWN as through it’s a real movie – and yet you make a valid comparison of the film to Stephen Sondheim’s musical play COMPANY. You also compare THE PIED PIPER to folk-horror like BLOOD ON SATAN’S CLAW, which even with the wealth of folk-horror studies, is a connection I haven’t seen made elsewhere. I also love that you compare Kris Kringle in SANTA CLAUS IS COMING TO TOWN to Kris Kristofferson in ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE! To me this is one of the things that makes you really unique as a film writer.

I love that you see certain kinds of films as being on the same playing field. As much as I’m a longtime fan of Peanuts films, I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone talk about YOU’RE A GOOD MAN, CHARLIE BROWN as through it’s a real movie – and yet you make a valid comparison of the film to Stephen Sondheim’s musical play COMPANY. You also compare THE PIED PIPER to folk-horror like BLOOD ON SATAN’S CLAW, which even with the wealth of folk-horror studies, is a connection I haven’t seen made elsewhere. I also love that you compare Kris Kringle in SANTA CLAUS IS COMING TO TOWN to Kris Kristofferson in ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE! To me this is one of the things that makes you really unique as a film writer.

Thank you! That’s lovely of you to say. Essentially film analysis should be interesting and unique! And in those examples you make there, it was very clear for me and I am completely genuine in this opinion. I feel that the episodic nature of YOU’RE A GOOD MAN CHARLIE BROWN which systematically deals with a boy’s alienation, personal worry, frustrations and depressive nature is a perfect match to the lead character in COMPANY, who is a bachelor surrounded by married friends who only want what is “best” for him. These two musicals are so similar in that way and mirror each other in terms of structure – both are told through dizzying vignettes. Yes, COMPANY is very adult themed and dark, but it still resembles the Peanuts show in a more cynical way. THE PIED PIPER is most definitely a folk horror film – did you know that one of the original posters for the film had it compared to two ecological horror movies that came out around the same time – promising to be more frightening than FROGS, BEN and WILLARD combined?!! But back to the issue of it being a folk-horror film, it is! It is as creepy and as moody as BLOOD ON SATAN’S CLAW or THE WICKER MAN, and has that ingredient of children in jeopardy which is always unnerving to watch. Finally, as far as Kris Kringle in the Rankin/Bass musical and Kris Kristofferson in the Martin Scorsese film, that is all about the changing face of the masculine – that men of the seventies would be strong and earthy but also sensitive and nurturing. They would also prove to be outsiders, rebels, non-conformists and gentle bearded creatives, which is a perfect summary of the aforementioned characters.

You talk about a 70s version of masculinity – in what way do you think the musical was affected by this new kind of masculinity? What are the signposts of this version of masculinity and was it more conducive to musicals or less so?

In this regard, I like to take into consideration men in relation to female protagonists. If you look at Billy Dee Williams in LADY SINGS THE BLUES and Frederic Forrest in THE ROSE, they are very similar. Left-over cowboys in a sense who have to understand their troubled and drug addled female partners who are both artists. Kris Kristofferson in A STAR IS BORN is a musician completely over his success and on the road to self-destruction all the while nurturing Barbra Streisand’s rising career while Gary Busey as Buddy Holly strides through the film with his masculinity firmly in place and never questioned. It’s amazing to see the defense of machismo securely noted in something SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, but then completely reconstructed in CAN’T STOP THE MUSIC.

How central were gender issues to these films in the 70s? Especially the fluidity of gender?

THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW really does address this in the most entertaining and wildly imaginative manner.

Both HAIR and OH! CALCUTTA! don’t just lionize their subjects – they do present problems that exist in ‘liberated’ communities – in OH! CALCUTTA! through the rape vignette and in HAIR with the criticism of being an intolerant person in real life while taking up causes left and right. But with HAIR, they address the issue and its moral stance is clear – in OH! CALCUTTA!, do you feel the rape scene is contextualized or is it just irresponsible?

A lot of people hate that vignette in OH! CALCUTTA! – and most of the others from the musical. I think it’s phenomenal. It is confronting and ugly and nasty and mean spirited, and totally important. Another vignette has a group of people writing in to an editor of a magazine talking about bestiality and other nasties, and in this one they are fully clothed and no sex acts are re-enacted, therefore I think just singing/talking about sex acts can be an easy pill for audiences, but to be confronted by a rape scene (and with the characters dressed as children no less) is something entirely different and harder to swallow. I don’t think it’s irresponsible at all, I think it’s a violent expression born from what is supposedly a liberated perspective and that is important, to ensure that these post-flower children sexually confident intellectuals can be just as repugnant as the rapists in films that surfaced around the same time as OH! CALCUTTA! hit the Broadway stage.

It’s interesting that you see so many films addressing Nazism (BEDKNOBS AND BROOMSTICKS, CABARET etc). Is this just because those directors came of age during WWII or is there some other cultural comparison going on?

I think it most certainly is a cultural comparison. The Nazis come to represent the death of expression and libertine values in CABARET and the “age of not believing” in BEDKNOBS AND BROOMSTICKS. The seventies was such an incredible period in that the youth culture was such a palpable influence on cinema – change permeates FIDDLER ON THE ROOF and that is completely a reflection of what was going on in society at the time: young people in the western world would be represented by the Sally Bowles of CABARET and their parents and authority figureheads that were trying to “reign them in” would be the oppressive Nazis that come to dominate the picture by the ghoulish end of Bob Fosse’s masterpiece.

It seems like the edgier musicals of the decade all started as stage plays. Why do you think that is?

It’s very simple – you could do a lot more on stage and get away with a lot more as far as themes, content and taboo breaking. It is always interesting to see how the stage musical will be opened up for film (I particularly love the ones that benefit from cinema such as FIDDLER ON THE ROOF and JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR) but also to see how much of the original anger, cynicism, mischief and so forth comes to fruition on the big screen.

You did a presentation related to the book when it was first released, correct? Can you tell me what the presentation consisted of and do you have any other similar events planned for it?

Yes, at the book launch I did a clip-and-tell lecture featuring a bunch of the films I discuss in the book. It was to give the audience an insight into how each of these movies were completely different and to explore themes that varied in each movie. I went from box office failures such as LOST HORIZON right through to huge successes like GREASE – the latter a movie completely embedded in the pop-culture’s mindset and yet unfairly maligned because of this. I would love to do this lecture again, and possibly add more clips to it with more obscure titles such as ROCK ‘N’ ROLL WOLF and the Italian JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR rip-off WHITE POP JESUS.

February 18, 2016

February 18, 2016  No Comments

No Comments