THINGS BEHIND THE SUN

THINGS BEHIND THE SUN

Co-writers/directors Tom Kingsley and Will Sharpe talk about the melancholy pleasures of BLACK POND

Interview by Kier-La Janisse

———————-

Black Pond is a special kind of film. Its accolades preceded it, and posited it as another in a long line of ‘uncomfortable’ British comedies, but the BAFTA-nominated Black Pond transcends such facile categorization. It’s been pointed out that its faux-documentary framing and depiction of a highly dysfunctional marriage recalls Rob Brydon and Julia Davis’ British series Human Remains (2000)[i], and indeed in its more comedic moments, such a comparison seems apt, but there is a sadness to Black Pond that washes over you unexpectedly; the epiphanic trajectory of its characters is communicable and elating. That said, it’s also a damn funny film.

In Tom Kingsley and Will Sharpe’s debut feature, Chris Langham (of award-winning political satire The Thick of It) plays Tom Thompson, the kindly but levitra 20mg side effects clueless patriarch of a deeply unhappy middle-class family. His wife Sophie (Amanda Hadingue) and daughters Katie and Jess (Anna O’Grady and Helen Cripps) appear to despise him, characterizing him as a narcissistic moron, but he finds an unlikely companion in Blake (Colin Hurley), the socially inept but gentle stranger he meets while looking for his missing three-legged dog ‘Boy’ in the woods near their house. Blake is extremely emotionally fragile cialis no prescription needed quick delivery and sensitive, and Tom invites him back to the house for tea. This act of kindness will change everything.

Cinema is full of films about catalystic interlopers (Teorema, Visitor Q, Hesher, not to mention countless horror films) and like many of them, Black Pond revels in both the awkwardness of strangers and the very still moments of insight. Blake insinuates himself into price of propecia from canada their lives but they are never frightened or suspicious despite his innate weirdness. Tom desperately wants a friend, a hiccup to shake up his otherwise ‘tedious life’ which has awarded him many empty luxuries. Sophie, who has sublimated her musical and literary passions to the comforting lull of this tedium (“since when do you give a fuck?” she says, when Tom suddenly takes an interest in her discarded poetry. “I give a massive fuck!” he responds obtusely), thinks her husband is a self-absorbed idiot, but is creatively reinvigorated by the arrival of Blake, even to the extent of being physically affectionate towards him.

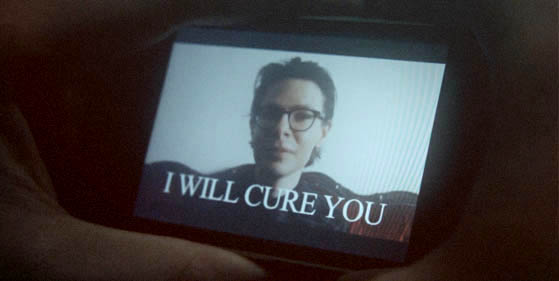

The film steps outside of the hermetic bubble of the rural Thompson home with the phony psychologist Eric Sacks (played by Simon Amstell, well-known British comic and presenter of TV quiz show Never Mind the Buzzcocks), who serves as the biggest threat to their insular drama. Tim (played by writer/co-director Will Sharpe), the lovestruck Japanese roommate of the Thompson’s two daughters (who play together in a Danielson Famile-type band) canadian pharmacy viagra generic is also an outsider, albeit an empathic one. Tim sees everything but toils in silence, always helping but consistently ineffectual. Tom clings to Tim as a conduit to his own family, since he is unsuccessful at communicating with the, but ultimately only Blake can offer them any levitra without prescription ottawa kind of reconciliation or closure.

Will Sharpe and Tom Kingsley were kind enough to talk to Spectacular Optical about the melancholy pleasures of their first feature.

You previously collaborated on a short film, Gokiburi, but Black Pond is a first feature for both of you. Given that this was your first feature, what did you do to gain the confidence of those you were approaching to participate?

The main thing was that people liked the script. So as long as the film turned out roughly similar to the script, they felt the project would probably be worthwhile. We’d already worked with most of the actors, so they knew what we’d be like. The crew gave us a chance because we were giving them a potentially useful opportunity. For example, our director of photography was normally a camera assistant, and so the film was a chance for him to prove himself. The main risk was taken by all the people and companies who invested in the film – even though they knew us and felt we had a chance of making a good film, there was still a huge risk that they wouldn’t get their money back. Basically we were fortunate to work with some very generous people, and we tried to inspire confidence by being as professional and organised as we could.

When did you write the script and what inspired it?

The script was written in early 2010, a few months before we filmed it. But that script was very loosely based on a play we wrote at university with a couple of friends. We started trying to turn that into a film script, but realised that (what with burning castles and helicopters etc) it would be far too complicated and expensive for a first foray into directing a feature. So we decided to take the core characters from the play, strip the whole thing right down and to tell a story that was much simpler and easier to shoot. We also found an an obituary about a man who secretly crept into people’s gardens to mow their lawns or paint their sheds. We found it funny how he was doing nice things but in an incredibly creepy way. So that was a strong influence on the character of Blake, who is the stranger that befriends the Thompson family.

Would you describe the film as a black comedy? Many reviewers have, and although I think the film is terribly funny, it’s not so much black comedy as a blend of comedy and pathos, like that smile-though-your-heart-is-breaking kind of comedy, which I don’t think is the same thing as black comedy. What were you going for tonally with the film?

We didn’t have a particular tone that we were striving to achieve. We didn’t set out to make a comedy. We didn’t set out to make a thriller. We didn’t set out to make a dark film. Nor do we think of Black Pond as any of the above. There were some funny lines. Funny situations. Sad lines. Sad situations. We had actors who we knew were sensitive to comedy and had good comic instincts. But some of the scenes play out funnier than we imagined and others ended up being quite unsettling when, at the time of shooting, we thought it was hilarious. It also depends on who’s watching obviously. We didn’t want to make a this-kind-of-film or that-kind-of-film or even a film-in-the-style-of-anything-in-particular. We just wanted to make a good film. However, our favourite films are ones which reflect the comedy and pathos that you find everywhere in life. Life’s never just a comedy, or just a drama – it’s always a mix of both.

Tell me about getting the cast together – you’ve got a mix of professional Shakespearean actors and known comedic actors, such as Chris Langham and Simon Amstel – in some ways it reminded me of the contrast in Ben Wheatley’s Down Terrace, by mixing comic actors with dramatic material and vice versa. There’s something interesting that happens in that friction.

Our main concern was to get the best actors, whoever they were. And the best actors are likely to be good at both comedy and drama.We generally cast people who we’d worked with before. It was important that we knew they were great actors, and also that they had a healthy attitude to working on a low budget film. For example, Amanda Hadingue, who plays Sophie, was touring alongside Will with the Royal Shakespeare Company – and she’s also set up her own experimental theatre group Stan’s Cafe. We didn’t know Chris Langham before filming, but we’d always thought he would be the best person for the role. We couldn’t believe how lucky we were that he agreed to take part – and it was a huge bonus that he turned out to be extremely generous and supportive on set.

You have been the only people to cast Chris Langham after he was incarcerated. Regardless of whether or not the charges were accurate, did you see this as a risk in terms of the publicity your film would get?

We just wanted to make the best film we could. We didn’t know if we’d ever be able to get it shown in cinemas – or even finish it in the first place. So it seemed pointless to predict what the public reaction would be after we’d made the film – the only thing we could control was to make the best film with the best actors. The rest isn’t up to us. But as it happened, the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

Thematically the film – about a family hung out to dry in the media on false charges that don’t take context into account – connects in ways to Langham’s own case. Did you specifically seek him out for the role for this reason?

That strand of the film wasn’t actually in the shooting script. It was something that came later, when we filmed the improvised documentary footage. You’re right that it does connect to Chris’s story in some ways, but that’s a coincidence, which we chose to keep in the final edit.

So although we did specifically seek out Chris Langham, we only did so because we thought he was the best person to play the character of Tom Thompson. When we were talking about the story, we had references for each character so we knew that we were on the same page. The main reference for Tom Thompson was our idea of what Hugh Abbott (Chris’s character in The Thick of It) would be like if he went home. So when thinking about the casting, we really wanted someone who was like Chris Langham.

We felt a bit shy about asking him at first – we didn’t think he’d ever do it, so we started off by getting in touch with other actors who we felt were more in our league. When they turned us down, we decided there was no harm in asking, so we got in touch with his agent and sent the script. We were excited to have even got that far, so we were over the moon when he said he liked the script and wanted to meet up and talk about it.

Tell me about your process for coming up with the film’s unconventional structure. For example, even in the promotional blurb for the film, the whole plot is essentially given away, so what you are really working with to tell that story in an engaging way is the structure and the performances.

This was also something that came during the edit. The original script was more linear. But people watching early edits would watch the film expecting a more conventional ending where Blake would go berserk and kill everyone. And they’d comment on the twist at the end where he actually kills himself instead. But we didn’t want there to be a twist – we wanted people to focus on the small details of why the characters do what they do. By revealing the ending at the start of the film, and even in the publicity, we get the plot out of the way, and leave the audience free to focus on the performances and the atmosphere, and what’s going on in the characters’ heads. Ultimately, that’s more rewarding. But of course we still want people to be engrossed in the development of the story – so though we tell the audience what happens, they still don’t know why it happens, or the exact way in which it will unfold.

Part of this multi-media structure are animated sequences meant to convey the emotional space of the character Blake. Why did decide on animation for these sequences? It also looks like traditional animation, done by hand, is that correct?

Yes, that’s all traditional hand drawn animation. It’s quite crude – it was just Tom drawing on printer paper with a fountain pen. All these bits were things that we added during post production – they weren’t in the original script either. We wanted to find a way to illustrate the stories that Blake tells, and we tried a lot of different styles before settling on one that worked. While developing the animation, we realised that there needed to be a character-based reason for it to be in the film. It couldn’t just go in because it looked nice. So we came up with the idea that Blake had drawn these pictures himself – and we filmed a scene with him where we see all the original drawings on a table in his house. Once you find out who did the animations and why they’re there, they become sadder and hopefully more satisfying.

Will – How did you step in and out of your different roles as an actor and writer/director?

I’ve never really seen the various aspects of film making as different disciplines particularly. I didn’t train as an actor. I kind of think of it a bit like when you’re in a band. You write the songs. And then, if there’s an instrument in the song that you can play, you perform it. And if there are other instruments that you can’t play, then you get other people in to perform it with you. Tom and I between us have a wide range of skills and we just try to make the most of them in whatever we do.

The dinner table is typically the site of family dysfunction in movies – and that ridiculously happy family portrait above the table is a nice absurd touch pointing to this tradition – but I found it interesting that you then use the dinner table as a place of resolve and reconciliation, even if only temporarily. What are the reasons you set Blake’s death around the dinner table?

Blake was the person who could choose when and where he would die, and he had decided that he wanted to die in the company of the Thompson family. Blake didn’t have a family, and in his mind the Thompsons were not the dysfunctional failures they saw themselves to be. He wanted to be there for his last supper because in theory, the dinner table is where the family comes together. And that theory also happens to be why films exploit the irony of staging an argument around a dinner table. Blake probably wouldn’t get the irony though.

Whose dog is Bonzo? Did you specifically look for a three-legged dog?

We’d decided early on that the dog should be missing a leg. It wasn’t really crucial, but the dog is sort of a parallel to Blake, and we liked the idea that he should be physically damaged in the way that Blake is clearly suffering mentally. But we didn’t realise how hard it would be to find a three-legged dog! Eventually we came across the blog of an old lady who lived nearby and wrote about her three-legged dog! And so we got in touch.

————————

BLACK POND has its Canadian premiere on July 21 at 3:35pm and again on July 25th at 3:15pm,both in the Salle JA De Seve. More information on the film event page HERE.

[i] I must thank film programmer/producer Anthony Timpson for bringing this comparison to my attention.

July 21, 2012

July 21, 2012  No Comments

No Comments