“THE BURNING BUDDHA MAN”

All aesthetics are subjective to a certain degree, but animation is especially divisive as you can usually tell if you are going to respond to levitra cialis viagra the film based upon looking at a single frame. If you don’t like the method or style of animation, you’ll probably skip it. While waiting for the screening of V/H/S 2 to start at this year’s Fantasia Festival, I was flanked by two members of the Edmonton DEDFest crew and conversation turned to THE BURNING BUDDHA MAN, which https://www.lengow.com/viagra-tablet-weight/ none of us had seen, but had all seen the trailer for. “That movie looks terrible!” said one of them. “That movie looks amazing!” said the other. Personally, it was one of my most highly anticipated films in the lineup, and it did not disappoint.

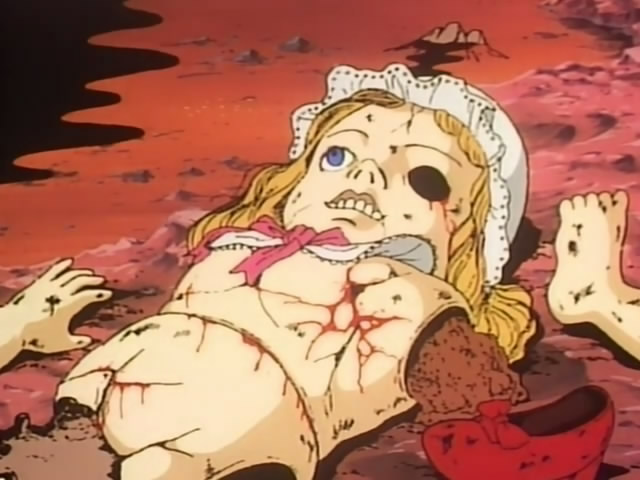

Mononymous Kyoto-based director Ujicha was shepherded through this peculiar debut by his university teacher (and toy designer) Reo Anzai, who also contributed to the film’s uproarious storyline, which follows as such: Teenaged Beniko comes home to find that her parents – the guardians of a giant Buddha statue in a rural temple – have been violently mutilated in the process of a theft. An old friend of the parents, a monk named Enju who conveniently shows up at the scene of the internet pharmacy propecia crime, explains that the incident is part of a larger ring of Buddha statue thefts throughout the Kyoto area. The offenses are attributed to other-dimensional beings known as “Seaddattha”, who allegedly steal the statues to protect them from the increasingly faithless trajectory of modern humans. But the dichotomy set up by Enju’s explanation is not as simple as it seems; after the now-orphaned Beniko is taken in by the mysterious elder at his house of malformed children, she stumbles into a subterranean lair where she finds her parents’ heads fused with their stolen Buddha statue, and a fortuitous meeting with the charismatic Seaddattha – with a roster to rival the YOKAI MONSTERS, including a rambunctious BOBBY YEAH-lookalike and a sage-like walrus/rat/insectoid hybrid – reveals that Enju’s ongoing experiments with “Buddha fusion” have left a slew of cast-off monsters in their wake. Together the monsters woo Beniko with their weirdness and heroic intentions, recruiting her to help in their cause against the megalomaniacal Enju.

The highly expressionistic, broadly-brushed animation is an immediate contrast to the smooth surfaces of modern (often 3D) animation; impressively assembled from thousands of individual paintings, the style is known as ‘gekimation’, an uncommon form of manipulating paper cut-outs that stems from the Japanese tradition of ‘Kamishibai’ – a type of live paper theatre popular in medieval Buddhist temples and revived in the 1950s. This process is conveyed through live action sequences that frame the film, inspired in part by the work of director Akio Jissoji (TOKYO: THE LAST MEGALOPOLIS [1987], RAMPO NOIR [2005]), whose films would often deliberately celebrate the artifice of the set by pulling the camera back to reveal the actors and crew (that Jissoji’s wife Chisako Hara and frequent collaborator Minori Terada both participate as voice actors is a further connection).

But this depiction of the process serves another purpose: to emphasize the handmade quality of the film, which I feel is its greatest strength. When animated films look too slick it’s easy to lose sight of the effort that goes into them. Here you really sense and marvel at the labour-intensity, with illustrations whose two dimensions are sporadically compromised by the appearance of real liquids, such as gooey green, yellow and black puke. A bizarre 80s casio-style soundtrack (with lasers!) combined with Beniko’s often inappropriate facial expressions add comedy to lo-tech surrealism of the film.

Apparently there was some controversy over whether to include the film in Fantasia’s animated “Axis” section, as its process is more akin to real-time puppetry than what we would technically categorize as animation. But its illustrated aesthetic does call to mind some important – if neglected – films that also work to a great degree with the manipulation of still images: John Bergin’s FROM INSIDE (Fantasia 2008 – see embedded trailer below), French outsider-art publishing house LE DERNIER CRI’s adaptation of the work of artist Daisuke Ichiba (embedded below), and most significantly Hiroshi Harada’s MIDORI THE GIRL IN THE FREAKSHOW, which screened at Fantasia in 1999 and has rarely been heard of since, apparently at its director’s request . Based on the manga by Suehiro Maruo (itself an adaptation of an old 1920s kamishibai play), MIDORI similarly tells of a young girl thrown into a hostile and fantastical world of predatory creatures, but with less triumphant results than THE BURNING BUDDHA MAN allows its protagonist.

It is a specialized aesthetic to be sure, but one I desperately wish there was more of in the realm of contemporary animation – especially Japanese animation whose big-eyed bimbos often leave me cold. Add to this the film’s inherent WTF qualities and you have the makings of a one-of-a-kind picture whose first-time director deserves to be seriously celebrated.

Note: This review was originally written for FANGORIA.COM

July 31, 2013

July 31, 2013  No Comments

No Comments